OVERVIEW

There is a relationship between English language proficiency and naturalization rates for United States immigrant populations, with higher English proficiency rates found among immigrants who apply for citizenship and successfully naturalize. Increasing English language proficiency among immigrants, therefore, seems to be positively related to naturalization. Given this positive correlation, policymakers can take steps to improve immigrants’ access to English language learning, including investing in English classes and making needed investments in programming that addresses systemic barriers to English acquisition.

U.S. CITIZENSHIP HISTORY

What is the history of citizenship and English testing in the United States?

There is no formal definition of citizenship outlined in the United States Constitution. The first U.S. legislative definition addressing the question of citizenship was the 1790 Naturalization Act, which stipulated that a citizen had to be a free white person that had resided in the U.S. for two year and was of good character and took an oath in support of the Constitution of the United States.[1] Such requirements changed over the course of the next century, with the most significant shift occurring when African Americans gained the right to citizenship in 1868 under the 14th Amendment. English language proficiency, however, remained distinct from the naturalization process until the 20th century, when the 1906 Naturalization Act instituted an English requirement for immigrants seeking citizenship.[2]

Further expanding on and institutionalizing this requirement, in 1952, the Immigrant Naturalization Act (INA) established the ability to speak, read, and write in English as a requisite component of naturalization. Per the INA, those seeking to naturalize would also be required to demonstrate “good moral character” and knowledge of U.S. history, government, and principles. Subsequently, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 first introduced the standardized naturalization test and strengthened educational requirements for citizenship. The test has been revised many times over the decades.[3] At present, learning English remains a central requirement of the naturalization process despite the fact that the United States does not have an official language.

What is citizenship and why is it important?

Although its meaning is widely recognized, the term “citizenship” has a formal legal definition. Broadly speaking, United States citizenship entitles a person to certain protections, privileges, and responsibilities within the country. On its website, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) paints a more idealistic picture of citizenship, stating that, “Citizenship is the common thread that connects all Americans. We are a nation bound not by race or religion, but by the shared values of freedom, liberty, and equality.”[4] Obtaining citizenship is considered to be an important step in the inclusion of immigrants into the country. According to USCIS, the benefits of U.S. citizenship include voting, bringing family members to the US, obtaining citizenship for children born abroad, traveling with a U.S. passport, becoming eligible for federal jobs, becoming an elected official, and demonstrating commitment to the U.S.[5] When an adult immigrant naturalizes, any of their foreign-born children under the age of 18 automatically become citizens, as well.

Citizenship improves employment prospects and economic opportunity for immigrants for a number of reasons. Some jobs are only open to citizens—particularly public-sector jobs such as civil service positions and jobs requiring security clearance. Private-sector companies that contract with the federal government for work requiring a security clearance may also prefer to (or be required to) hire citizens. Certain licensed professions require citizenship as well, and other employers prefer to hire citizens over noncitizens, often due to misconceptions about immigrants’ eligibility for employment.[6] It has further been found that, “Naturalized citizens earn between 50 and 70 percent more than noncitizens. They have higher employment rates and are half as likely to live below the poverty line as noncitizens.”[7]

What are the requirements to become a U.S. citizen?

For immigrants to naturalize, they must meet the following requirements:

- Have lived in the U.S. with lawful permanent residency status for at least five years. Alternatively, those who have been married to a U.S. citizen for at least three years are eligible to apply for citizenship after three years of lawful permanent residency.

- Pass a criminal background check.

- Pay an application fee. The fee has increased over time, but a fee waiver is available for applicants who demonstrate that they are unable to pay the filing fees.

- Demonstrate English language proficiency and knowledge of U.S. history and government through the naturalization test.

During the naturalization test, an applicant’s English proficiency is evaluated under both the interview and written portions of the test. Contrary to a common misconception, there is no separate English test for naturalization; rather, the assessment of English skills is integrated into the process. The naturalization test consists of two components: English language proficiency—determined by the applicant’s ability to read, write, speak and understand English—and knowledge of U.S. history and government, determined by a civics test.[8] Applicants must also be able to act on basic commands, follow directions, and respond to questions during the naturalization interview.[9] USCIS recommends that immigrants with limited English language proficiency enroll in a basic-level English course before scheduling their citizenship interview.

Components of the naturalization test:

- Civics: Applicants must correctly answer aloud 6 of 10 questions that they are asked. Test questions are selected from a list of one hundred questions that USCIS makes available online for applicants to study in advance.

- Reading: Applicants must read aloud 1 of 3 reading test sentences correctly. Reading vocabulary is available online. The content focuses on civics and history topics.

- Writing: Applicants must write 1 of 3 sentences correctly that the USCIS officer reads aloud. Writing vocabulary is available online. The content focuses on civics and history topics.

- Speaking: Applicants must demonstrate an understanding of and ability to respond meaningfully to questions in English during the eligibility interview.

An applicant has two opportunities to pass the English and civics tests: the initial examination and the re-examination interview. The naturalization application is denied if the applicant fails to pass any portion of the tests after two attempts. Exemptions are available for those individuals seeking to naturalize who meet certain criteria. Applicants 50 or 55 years old and older who have resided in the United States for 20 or 15 years respectively may be exempt from the English portion and provided the opportunity to conduct the interview and answer the civics portions with an interpreter. It should be noted that an applicant is responsible for bringing his or her own interpreter. For some applicants, this is an additional barrier to pursuing naturalization as they would need to pay for a qualified interpreter. Individuals with medical disabilities can apply for an exemption from English, civics, or both requirements.[10]

Pass rates for both the English language and civics test are very high. In 2021, the pass rate for applicants who took the initial exam only (including applicants who were exempt from one or more portions of the test) was 89.5 percent. The pass rate for those who took the initial and re-exam (as well as those who were exempt from one or more portions) was 96.1 percent.[11] This data, however, tells only part of the story. Many immigrants with low English proficiency—held back by their belief that their language skills are insufficient to pass the test or by difficulty understanding the administrative process due to low proficiency—likely never reach the point of taking the test.[12]

What level of English is required for the U.S. citizenship test?

Section 312 of the INA classifies the level of English required to pass the naturalization test as “ordinary English usage.”[13] More specific information about the required level of English proficiency, however, is vague, with “basic proficiency” being one of the most common descriptors. As a point of reference an A1 “Beginner” English course has a vocabulary of approximately 700 words, and an A2 “Pre-Intermediate” English course has a vocabulary of approximately 1500 words. The average vocabulary of a 10 year old, normally grade 4 or 5, is about 20,000 words.

Analysis of the naturalization test material has also revealed that the required level of English proficiency may be higher than is claimed.[14] Critics note that, “because the level of conversational English necessary to pass is at the interviewer’s discretion, interviewers are free to fail those whose English is nonstandard or not easily understood.”[15] USCIS is currently in the process of development a redesign of the naturalization test including the English speaking part of the test and the format and content of the civics portion of the naturalization test.

Critics have also argued that the civics test requires a higher level of English language skills than is set forth under the English requirements. While USICS encourages applicants to take a basic English course prior to their interview, such a course does not necessarily teach the vocabulary necessary to cover all the civic topics that can be included in the test, unless the class is specifically designed as a naturalization preparation class. For example, legal terms and concepts found in some of the naturalization test questions – like: “Name two important ideas from the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. Equality, Liberty, Social contract, Natural rights, Limited government, Self-government.” Such questions often require a higher level of English proficiency, and questions can be inconsistently asked by officers during the interview. As a result, an interviewer can fail applicants who are proficient at speaking “ordinary” English, but lack the vocabulary to handle more advanced terminology in the civics test.[16] That USCIS makes the civics questions and reading and writing vocabulary available on line is essential for study purposes. However, because some immigrants memorize the civics questions and reading and writing vocabulary, whether or not the test accurately assesses English or civic proficiency has been debated. Even with this memorization of prep materials an applicant can still fail the test based on the interviewer’s discretion.

NATURALIZATION CONTEXT

What are the current trends in immigrant naturalization?

According to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), there were 23.2 million naturalized U.S. citizens in the United States in 2019, making up 52 percent of the overall immigrant population of 44.9 million.”[17] Data from the Pew Research Center reveals that between 2005 and 2015, most of the United States’ 20 largest immigrant groups, by country of origin, experienced increases in naturalization rates. During this time period, the total number of naturalized immigrants in the U.S. increased by 37 percent from 14.4 million in 2005 to 19.8 million in 2015.[18] USCIS reports that it welcomed 809,100 new citizens in fiscal year 2021 while recovering from pandemic-related closures.[19]

What are the factors that affect naturalization rates?

Several interrelated factors have been found to contribute to immigrant naturalization rates. An analysis by the Migration Policy Institute finds that immigrants who have high levels of education, speak English well, and have been in the United States for a long time are more likely to naturalize.[20] A study conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2007 indicates that income plays a role as well, as higher income correlates with increased naturalization rates.[21] The study additionally corroborates the connection between length of time in the U.S. and naturalization rates: “the longer immigrants have been in the U.S., the more likely it is that they will become citizens.”[22] Importantly, this connection is in part attributed to the ability of immigrants to develop their English skills over time; Limited English Proficient (LEP) immigrants might become more confident about applying for citizenship as their English improves with practice.[23]

Improving English over time has implications for immigrants who come to the U.S. later in life, such as grandparents, who will not have the same time advantage as younger immigrants. In addition, studies have shown that while older adults can learn new languages, it is more difficult to learn a new language when older. USCIS recognizes this challenge through the existing 50/20 and 55/15 language waivers. The 5o/20 wavier means, a 50-year-old who has been an LPR for 20 years is exempt from the English language requirement. However, USCIS should expand on these waivers to include a 60/10; 65/5 and 70/0 exception as well. That would mean that someone who is 70-years old and has LPR status is automatically exempt from the English language requirement.

English proficiency also appears to correlate with education levels, with the well-educated enjoying increased levels of English proficiency. One study proposes several reasons that immigrants with more schooling are more likely to naturalize, including greater English language proficiency and greater ease in passing the civics portion of the naturalization test. It also notes that, “a wider range of job opportunities for the more highly educated citizens may provide an economic incentive for naturalization to increase with educational attainment.”[24]

Immigrants are also more likely to naturalize if they perceive the benefits of citizenship to be greater than the costs of applying.[25] One report, Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada, stated that, “For those who are college educated, proficient in English, and comfortable with bureaucracy, the process is annoying but manageable.” To an immigrant with limited schooling, poor English, and an inability to navigate bureaucratic systems, however, “naturalization may appear formidable.”[26] Greater English proficiency may help tip the scales in favor of pursuing naturalization, as immigrants possessing such skills need not devote as much time and effort developing them prior to applying for naturalization. MPI research identifies obstacles to naturalization as low English language proficiency, lack of knowledge about the application process, and the application fee.[27] It makes sense, then, that immigrants are less likely to obtain U.S. citizenship if they have lower English skills, education levels, and income—all factors that are often closely correlated to each other.[28]

A leading study on the various factors affecting naturalization rates among U.S. immigrants shows the a clear correlation between English language proficiency and citizenship rates.[29] The data shows this relationship extends across gender lines. While females were more likely than males to naturalize across all English proficiency levels, similar patterns in the correlation between English proficiency and naturalization rates were found for each gender.[30]

ENGLISH CONTEXT

What English services are available to immigrants?

The federal government provides financial support for states to administer English language training services under the nation’s adult basic education and workforce development law, namely, the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA).[31] This federal-state partnership system is the primary means through which English language services are offered to adult immigrants and refugees.[32]

Under this model, while states receive federal funding to administer English services, they maintain the discretion to fund and structure programs largely as they see fit. Accordingly, significant variation exists between states’ financial contributions to adult education, and therefore English Language Learning (ELL) programming. Program design and administration also varies by state, as does the level of participation of adult English learners enrolled in classes.[33] Across states, multiple levels of ELL classes are typically offered and students’ progress is assessed through testing during the course. While some immigrants can access ELL classes at no cost through local English language providers, refugees benefit from specially designed English services which they can access through separate local resettlement affiliates. Unfortunately, while these systems are available to most immigrants in theory, MPI finds that the demand and need for adult education services is far greater than the available services, “they meet only a fraction of the total need for all adult education services nationally—less than 4 percent.”[34]

Passing the citizenship test clearly requires command of the English language. However, English proficiency has much broader implications for immigrants beyond passing the citizenship test. It contributes to job security and job advancement and is essential for learning to navigate U.S. systems and services requisite to inclusion, such as healthcare, education, and housing. Research has found that, “English language ability ranks as one of the key human-capital traits that immigrants must master to succeed in the U.S. labor market.”[35]

The fact that only a small percentage of adult English learners can access these programs undermines immigrant inclusion. Flaws in the nature and design of instruction like not assigning value to digital skills or other inclusion outcomes create obstacles to immigrant integration. In recent years, federal-state funding cuts for English and family literacy programs serving parents, as well as other immigrant integration services, have further exacerbated such problems.[36]

What are workforce-focused English-language programs?

Alternatively, a different workforce-focused ELL model for English-language instruction has proven to be effective. Programs based in workplaces and targeted to the needs of employers, like the National Immigration Forum’s English at Work program, have yielded positive results.[37] This program partners with businesses to offer industry-contextualized English language training at the worksite. The training is a blended course consisting of 40 percent live instruction and 60 percent online learning accessible on a desktop computer, tablet, or mobile device.

English at Work’s first-of-its-kind curriculum combines best practices in English language learning and worksite competencies to respond to employer operational needs. After just 12 weeks of English training, 87 percent of the participants demonstrate improved English skills, 37 percent report being promoted, and 93 percent reported improved job performance.

In the “English at Work” program, 61% of the participants said they were somewhat or very much on track to becoming a U.S. citizen after the English training, compared to 49% before the training. Research shows that immigrants with greater English proficiency enjoy higher incomes and occupy more positions in skilled jobs than those with low proficiency. This trend holds even after controlling for differences in education and skill associated with language abilities.[38]

In addition to yielding encouraging results, workplace-based English instruction has a number of benefits over the traditional federal-state partnership model. First, because they are often located at the worksite, and in some situations during work hours, they save adult workers the time and expense of traveling after work hours to off-site English classes. Also, because they are worksite-focused, they can provide English instruction specific to the workplace that enhances work quality and productivity. A Migration Policy Institute (MPI) report explains, “While generic language training programs that provide language ‘survival skills’ for everyday interactions serve an important purpose, language training that is contextualized for workplace use is essential to the long-term self-sufficiency and economic success of many immigrants and of the businesses that rely on their labor.”[39]

In addition, worksite ELL also addresses a key problem facing language integration programs – cost. Classroom instruction is expensive, and worksite English training provides a cost-effective alternative.

What are the rates of English acquisition by immigrants?

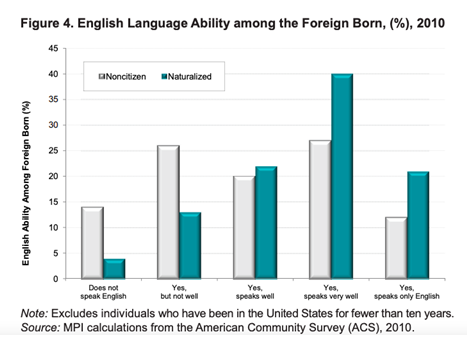

American Community Survey data from 2013 revealed that 69 percent of all full-time immigrant workers in the United States were Limited English Proficient (LEP) or low LEP.[40] English proficiency increases with the length of time lived in the U.S. In 2018, 47 percent of immigrants living in the U.S. five years or less were English proficient, while 57 percent of immigrants who lived in the U.S. for 20 years or more were proficient.[41] MPI reports that in 2010, noncitizens were “about four times as likely as citizens to report not speaking English, and twice as likely to report not speaking English well” (see Figure 4 below). Furthermore, according to a 2005 estimate, 55 percent of LPRs eligible to naturalize were LEP, compared to 38 percent of naturalized citizens.[42]

What are the barriers to English acquisition?

In the program year 2013-14, only 46 percent of adults in federally supported ELL programs completed the level in which they were enrolled. Fifty-four percent of such adults “separated before they completed” or “remained within level.”[43] Several barriers to accessing English-language education—especially common among low-income immigrants—are thought to negatively affect persistence and progress in these programs. Immigrants commonly cite work conflicts, transportation challenges, and childcare issues as primary barriers to continued participation in ELL education.[44] The delays in English-language acquisition that such barriers create have lasting, harmful effects on adult immigrants’ opportunities and integration, and can also negatively impact their children’s success.[45]

The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report, identifies challenges in English-language education programming that contribute to low English acquisition rates. One such challenge is decreased efficacy and reach of English education programs—particularly those funded under Title II of WIOA. Program enrollments in WIOA English classes have been on the decline, in part this is due to funding declines in English education programs because states’ matching grants are locked into other programs that met WIOA’s narrow performance requirements. Other barriers are work conflict, transportation, and child care. In the program year 1999-2000, states enrolled 1.1 million adults in ELL classes—a number which fell to 667,000 enrollees for 2013-14.

Another issue is that adult education programs often have an overly long-time sequential horizon. Many programs, especially those for ELLs, begin with English-language learning, then proceed to obtaining a secondary education credential, and finally end with postsecondary education or professional credentials.[46] The Integration of Immigrants into American Society argues that, “this long, attenuated process often does not match the time and economic pressures many low-income adult immigrants experience today, making persistence and progress in [English as a Second Language-ESL] classes and low transfer rates from adult secondary education to postsecondary education a source of abiding policy concern.”[47] Such factors coalesce to forestall immigrants’ acquisition of English and, accordingly, advancement in the workforce. The shorter and direct application of contextualized English offerings would suggest that such programs would serve as a better onramp, than traditional ESL, to postsecondary education, which in turn leads to increased pay, benefits, and opportunities for career growth, as well as naturalization.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Increase funding for ELL programs.

Federal and state funding for adult education and English instruction should be increased. Support has been declining in recent years, and demand far exceeds supply. Federal and state support for these services must increase to align with the demand.

2. English learning opportunities for immigrants should be expanded through the evaluation of effective programs and improved program design.

Federal and state agencies should evaluate which ELL programs are most effective in supporting immigrants’ continued participation and progress in English learning, and, ultimately, their successful English language acquisition. Information about promising programs should be shared broadly for replication by other jurisdictions, organizations, and employers. Enrollment of participants in ELL programs should be directly linked to appropriate performance measures including inclusion measures such as digital skills.

3. To increase naturalization rates, accessibility to ELL classes should be improved through systemic changes that address practical barriers to participation.

ELL programs must take into account the needs of working adults, including students with child care responsibilities or job schedules that make it difficult to attend classes. Courses should be offered at times that fit into the schedules of these students, and providers should offer supplemental services such as child care and help with the cost of transportation and course materials. Such remedies will increase ELL students’ participation, advancement, and completion of their courses.

4. To facilitate immigrants’ advancement in the workforce, ELL services that are contextualized to immigrants’ worksites and their sector of employment should be further developed and implemented more broadly.

Contextualized programs have shown promise in expediting learning that will have a more immediate economic impact. They also eliminate scheduling conflicts that often preclude immigrants from attending ELL classes. As worksite classes require buy-in from employers, employers should be better educated on the benefits of these programs. Furthermore, partnerships should be pursued to increase awareness about and capacity to respond to the skills needs of an area’s employers and workforce, as well as the language training needs of area workers.

In addition, policies should be developed that create incentives for employers to include English training as part as their regular training offerings. Current WIOA requirements do not offer a streamlined way that employers can navigate and tap into WIOA funding. Partnerships between public, nonprofit, and private educational providers (especially community colleges), employers, labor unions, business associations and community organizations will facilitate the development of programs and curricula for adult learners that are aligned with the needs of employers.

5. The language wavier for naturalization should be expanded so that it scales for the elderly. Current language waivers for naturalization should be expanded on a sliding scale for elderly and long-term U.S. residents. Doing so would take into consideration an important principle that language acquisition becomes more challenging as an individual ages, and as their opportunities for social and work-related English language exposure decreases. Such exceptions also reflect the fact that older adults do not have the same extended time advantage to increase their English skills.

6. More research should be conducted around the correlation between English proficiency and naturalization for U.S. immigrants.

Additional research delving further into the direct connection between English language proficiency would be helpful, especially if it can separate out other concomitant factors affecting naturalization rates. Federal and state agencies should continue to engage in research on this topic to develop empirically-backed updated initiatives that concurrently improve English proficiency and naturalization rates—especially among socioeconomically disadvantaged immigrant populations.

7. More research should be conducted to evaluate the required level of English for the current naturalization exam and determine if it exceeds the law’s intent for “basic” or “ordinary English usage.”

Policymakers should consider whether the civics portion of the naturalization test requires a higher level of English language skills than is set forth under the English requirements. Should it be found that the required level of English is, indeed, higher than indicated, USCIS must update the naturalization test to better reflect the language level it claims is necessary for the exam

Examining this issue and updating the test accordingly will provide service providers with the opportunity to develop curriculum and instruction plans that effectively prepare applicants for their English test at the appropriate level of proficiency. And future modifications to the naturalization exam should honor the law’s intent and should not be made in a manner that tests beyond the basic or ordinary English usage requirement.

CONCLUSION

A correlation between English language proficiency and naturalization rates is evident among U.S. immigrant populations. Naturalized citizens have been found, through several studies, to possess higher levels of education and English language proficiency than noncitizens. Naturalized citizens also tend to have spent longer in the United States than noncitizens, allowing more time to develop English skills as well as to gain critical cultural knowledge.[48] All three factors reinforce one another, deepening existing patterns.

Federal, state, and local policymakers should accordingly take steps to increase immigrants’ access to English-language education, reducing barriers, modernizing ELL programing to maximize opportunities for immigrants to improve their English proficiency. Such investment would increase naturalization rates as it enhances immigrants inclusion and career advancement prospects.

The National Immigration Forum would like to thank Brenley Markowitz, policy intern, for her extensive contributions to this paper.

[1] https://www.visitthecapitol.gov/artifact/h-r-40-naturalization-bill-march-4-1790

[2] Irene Bloemraad, Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada (California: University of California Press, 2006), 22.

[3] Loring, “The Meaning of Citizenship: Tests, Policy, and English Proficiency,” 200.

[4] “Should I Consider U.S. Citizenship?,” Citizenship Resource Center, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, accessed October 19, 2022.

[5] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “What Are the Benefits and Responsibilities of Citizenship?” In A Guide to Naturalization, 3.

[6] Madeleine Sumption and Sarah Flamm, “The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute (September 2012): 4.

[7] Sumption and Flamm, “The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States,” 11.

[8] “English and Civics Testing,” Citizenship and Naturalization, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, accessed October 17, 2022.

[9] “Identifying the English Language Skills and Civics Knowledge for Naturalization,” Adult Citizenship Education Strategies for Volunteers, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, last updated May 30, 2020, accessed October 17, 2022.

[10] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “English and Civics Testing.”

[11] U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Naturalization Statistics.”

[12] Sumption and Flamm, “The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States,” 5.

[13] Loring, “The Meaning of Citizenship: Tests, Policy, and English Proficiency,” 211.

[14] Loring, “The Meaning of Citizenship: Tests, Policy, and English Proficiency,” 198.

[15] Loring, “The Meaning of Citizenship: Tests, Policy, and English Proficiency,” 211.

[16] Loring, “The Meaning of Citizenship: Tests, Policy, and English Proficiency,” 211–212.

[17] Maria Gabriela Sanchez and Jeanne Batalova, “Naturalized Citizens in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, November 10, 2021.

[18] Ana Gonzalez-Barrera and Jens Manuel Krogstad, “Naturalization rate among U.S. immigrants up since 2005, with India among the biggest gainers,” Pew Research Center, January 18, 2018.

[19] “Naturalization Statistics,” Citizenship Resource Center, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, accessed October 19, 2022.

[20] Sumption and Flamm, “The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States,” 1.

[21] Jeffrey S. Passel, “Growing Share of Immigrants Choosing Naturalization,” Pew Research Center, March 28, 2007.

[22] Passel, “Growing Share of Immigrants Choosing Naturalization.”

[23] Mary C. Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2015), 168.

[24] Barry R. Chiswick and Paul W. Miller, “Citizenship in the United States: The Roles of Immigrant Characteristics and Country of Origin,” IZA Journal of Labor and Economics, no. 3596 (July 2008): 21–22.

[25] Chiswick and Miller, “Citizenship in the United States: The Roles of Immigrant Characteristics and Country of Origin,” IZA Journal of Labor and Economics, no. 3596 (July 2008): 40.

[26] Bloemraad, Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada, 80.

[27] Sumption and Flamm, “The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States,” 1.

[28] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 170.

[29] Chiswick and Miller, “Citizenship in the United States: The Roles of Immigrant Characteristics and Country of Origin,” 21–22.

[30] Chiswick and Miller, “Citizenship in the United States: The Roles of Immigrant Characteristics and Country of Origin,” 16–17.

[31] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 81.

[32] Margie McHugh and Catrina Doxsee, “English Plus Integration: Shifting the Instructional Paradigm for Immigrant Adult Learners to Support Integration Success,” Migration Policy Institute (October 2018): 3.

[33] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 81.

[34] McHugh and Doxsee, “English Plus Integration,” 1.

[35] Anthony Carnevale et al., “Understanding, Speaking, Reading, Writing, and Earnings in the Immigrant Labor Market,” American Economic Review 91, no. 2 (February 2001): 159.

[36] McHugh and Doxsee, “English Plus Integration,” 1.

[37] Margie McHugh and A. E. Challinor, “Improving Immigrants’ Employment Prospects through Work-Focused Language Instruction,” Migration Policy Institute (June 2011): 3.

[38] McHugh and Challinor, “Improving Immigrants’ Employment Prospects through Work-Focused Language Instruction,” 2.

[39] McHugh and Challinor, “Improving Immigrants’ Employment Prospects through Work-Focused Language Instruction,” 6.

[40] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 81.

[41] Abby Budiman, “Key findings about U.S. immigrants,” Pew Research Center, August 20, 2020.

[42] Sumption and Flamm, “The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States,” 8.

[43] Mary C. Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society (Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press, 2015), 81–82.

[44] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 81–82.

[45] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 317.

[46] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 82.

[47] Waters, The Integration of Immigrants into American Society, 82.

[48] Sumption and Flamm, “The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States,” 5.