I. Introduction

The focus of this paper is on immigrants in the professional health care sector, particularly physicians[1] and registered nurses.[2] The paper examines the growing need for professional health care workers, the role immigrants already play in the professional health care sector, the important role immigrants can play in helping fill the professional health care shortages, and recommendations addressing legislative solutions.

II. The Health Care Worker Shortage

Several key professions that comprise the health care workforce currently face shortages. In contrast to the 1980’s, when there were reports of physician surpluses that would continue to grow into the 1990s, recent decades have seen health care workforce shortages. Beginning in the 2000’s, professional health care worker shortages were being identified and highlighted. For example, in a 2009 publication by the Institute of Medicine – Ensuring Quality Cancer Care through the Oncology Workforce: Sustaining Care in the 21st Century: Workshop Summary (2009) – the authors contended that “by 2020, there will be an 81 percent increase in people living with or surviving cancer, but only a 14 percent increase in the number of practicing oncologists. As a result, there may be too few oncologists to meet the population’s need for cancer care.” In the summary, the authors assert that: “These workforce shortages are problematic because they will lessen both the access to and the quality of care available for cancer patients and may increase the burden on families of individuals with cancer.” What the experts were not able to predict was the COVID-19 pandemic which led to even greater disparities than projected.

In 2019, an industry report by a leading physician search firm, indicated that while there were shortages in primary care physicians, even greater shortages existed for specialists. The report found that the situation was especially heightened for specialists who deal with seniors, reflecting an aging population that is living longer and has growing needs, with serious public health implications. Also in 2019, echoing that finding, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), reported that the shortage of primary care physicians by 2032, well into the future, would be between 21,100 and 55,200 and for specialty care physicians it would be between 24,800 and 65,800.

In late 2024, the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA) put forward detailed projections for a broad range of professional health care occupations, with demand far out numbering supply (and increasingly so) between 2022- and 2037. In 2025, the publication STAT posted an article calling the physician shortage “dramatic,” projecting that by 2037 there would be a physician shortage of approximately 187,000. According to STAT, the shortage would be much more severe in rural areas, with rural areas “projected to face a 56% shortage compared to 6% in urban areas.”

A. Increased Demand for Health Care Workers in the U.S.

One of the factors driving the growing need for professional health care workers is that the senior population is growing. The large Baby Boomer population (“Boomer”) is retiring, living longer, and has increased health care needs, while Boomer-aged physicians, surgeons, and nurses are retiring. Statistics show that 6 out of 10 adults have at least one chronic health condition. Approximately 11,200 Boomers will be turning 65 every day starting in 2024 through 2027, representing about 4.1 million new Boomer senior citizens every year.

Boomers were the largest generation in U.S. history. Between the large number of Boomer health care workers retiring and the broader Boomer population needing more and more services from health care professionals, the health care sector faces challenges both in terms of the retiring of health care workers, and in terms of the demand for increased services. The retirement of Boomers is significant enough to have secured the nickname “silver tsunami.”

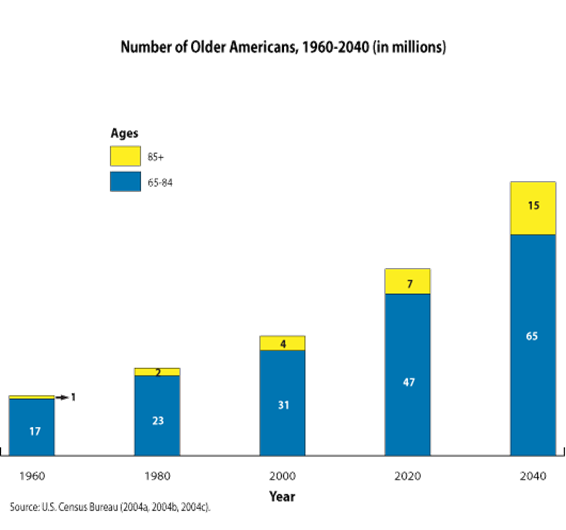

Even beyond the Boomer generation, the U.S. population at large is aging, as lifespans grow and families have fewer children. Studies have projected that between 2000 and 2040, the American population age 65+ will double to 80 million, representing 1 out of every 5 people in the U.S. Those ages 85 and older are projected to quadruple in the same time period.

Source: Urban Institute

1. Health Care Workforce Attrition

The health care sector is facing a major challenge – attrition, particularly by workers leaving the sector because of burnout. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the sector experienced a “Great Resignation” – with 18% of health care workers leaving their jobs. In 2022, close to the peak of the pandemic, surveys indicated that approximately a quarter of doctors and nurses stated that they were ready to leave their jobs. In the same time period, a clear majority of physicians surveyed – 62.8 % – said they were experiencing burnout, a number that has since declined, falling to below 50% in 2024. While the turnover rate is coming down, it remains a concern. Even with health care professionals experiencing less burnout after the peak of COVID-19, pandemic-era resignations and job shifts remain an ongoing challenge. A 2024 survey found that 62% of physicians had made a career change in the last two years. A new 2025 study shows incomplete clinical team staffing has persisted and has had a measurable impact on burnout, representing another important contributing factor to health care workers leaving their positions.

Nursing has also faced similar challenges. A study of registered nurses by Health Affairs found that more than 100,000 registered nurses left the profession between 2020 and 2021 following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This represented an unprecedented decline across 40 years of available data, with the highest percentage of turnover coming from RNs who were under the age of 35. These younger nurses were in the prime of their nursing careers and chose to leave the profession, creating workforce gaps that will continue to be challenging to fill in 2025 and beyond. Also of note, the post-pandemic decline in the demand and number of travel nurses – short-term RNs who work under contract outside their home area – has occurred in recent years.

While COVID-19 played a major role in these resignations, the sector was already facing attrition, with doctors and nurses leaving the sector even before the pandemic. Before the pandemic, U.S. doctors had a burnout rate twice that of other workers, and a higher rate of suicide than the general public. Numerous factors contributed to all these resignations including work overload, inadequate compensation, lack of control over decision-making, and perceived shortcomings in community and teamwork within the health care sector such as the conflicting interests between quality patient care and controlling overall costs.

2. Growing Life Expectancy

Another contributing factor to the shortage of professional health care workers is that Americans will live longer in the coming decades. Not only is the average life span already increasing, but health care needs are also growing among the aging population. In 2022, out-of-pocket health expenses for those 65 and older represented about 14% ($6,668 on average) of their overall expenditures, compared to 8.4% ($5,177 on average) for Americans of all ages. Similarly, people over 55 make up less than 33% of the U.S. population, but account for a majority (56%) of total health expenditures. As this elderly population grows and has more health-related needs, the nation will need more professional health care workers.

B. Immigrants in the Health Care Sector

Immigrants represent a key portion of the overall health care workforce. They currently make up more than a quarter (26%) of physicians and surgeons. In some areas, like California, the District of Columbia, Maryland, New York, Florida, and New Jersey that number is even higher – about one-third (32-37%). Approximately 16% of all registered nurses are immigrants, a number that is expected to grow in the coming years.

1. Conrad 30 Waiver Program

A noteworthy federal program that recognizes the important role immigrant physicians play in the health care sector is the Conrad 30 Waiver Program. Conrad 30, which was created via congressional statute, helps immigrant medical school graduates start their careers while providing essential health care personnel to medically-underserved communities. Rather than having to follow the standard rule of returning to their home countries for two years before they are eligible to practice medicine in the U.S., Conrad 30 allows foreign medical graduates with J-1 visas to commit to work in medically underserved areas (MUAs) for three years, allocating up to 30 slots per state. MUAs are “geographic areas and populations with a lack of access to primary care services.” While Conrad 30 has benefited dozens of communities since its initial creation in 1994 (initially as the Conrad State 20 program with only 20 slots per state), it remains small and could have further reach if expanded by Congress, aiding additional communities and launching the careers of more doctors.

2. Immigrant Health Care Workers During COVID-19

During COVID-19, the essential role of immigrants in health care jobs and other sectors became abundantly clear. It led to the introduction of bipartisan legislation, the Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act, that would recapture tens of thousands of unused employment-based visas for physicians and nurses to help address the national emergency. However, Congress has yet to act on that bill since it was first introduced in 2020 as a response to pandemic-era health care workforce shortages.

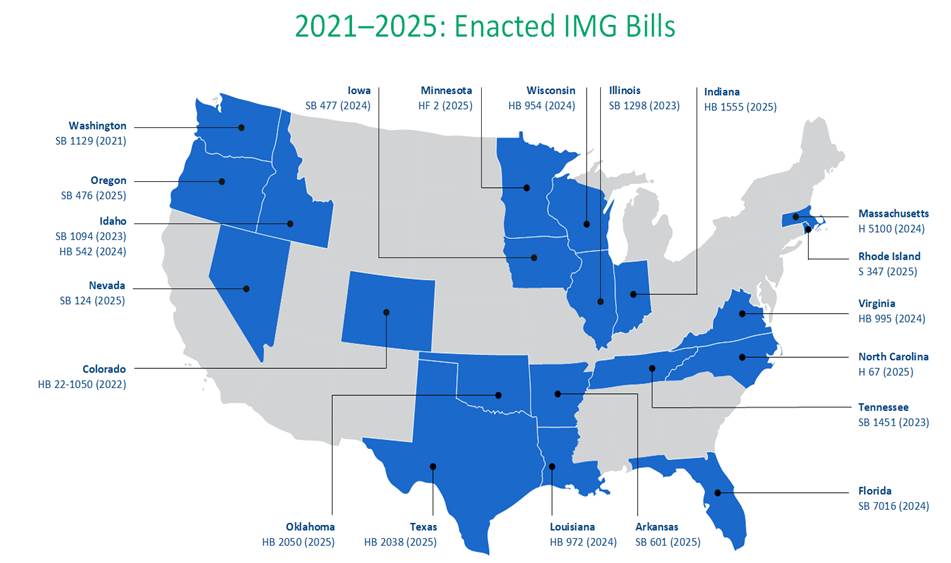

For individual states, the important role immigrants played during the pandemic helped push a number of them to find ways to remove licensing barriers that prevented many immigrants with professional credentials — including those with relevant overseas health care workforce educations and licenses – to enter the workforce in their sectors of expertise. This has continued and a growing number of states are working to address these licensing barriers. As report by WES, as of early July 2025, twenty states (Washington, Colorado, Illinois, Tennessee, Idaho, Iowa, Wisconsin, Massachusetts, Virginia, Louisiana, Florida, Arkansas, Indiana, Minnesota, North Carolina, Nevada, Oregon, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Texas), have passed legislation to remove licensing barriers for International Medical Graduates (IMGs).

3. Dreamers in the Health Care Workforce

Similarly, DACA recipients filled essential roles in the health care sector during the COVID-19 pandemic and have continued to serve in crucial workforce roles today. It is estimated that at the beginning of the pandemic in April 2020, some 29,000 DACA recipients worked in health care sector jobs in varying skill-level positions, including 3,400 registered nurses. DACA recipients continue today to make important contributions as health care workers and more Dreamers could fill essential jobs if they were able to obtain legal work status. Since 2017, tens of thousands of new Dreamers have not had their DACA applications adjudicated, limiting their opportunities to obtain work authorization and enter the health care workforce.

Despite these hurdles, 86 Dreamers, more than three-quarters of which (77 %) have been unable to receive DACA protections, have enrolled in the “Pre-Health Dreamers” (PHD) program for students to study health-related professions as part of the Peer Engagement and Enrichment Program (PEEP).The nationwide program is a “graduate pipeline program for undocumented students pursuing health professions.” During the 2024 academic year, nearly 70% of those in the program were pursuing a career in medicine.

C. Health Care Workforce Shortages Projected to Continue

Workers’ shortages are expected to persist in the current post-pandemic era, into the next decade. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) projects that by the year 2036, the U.S. physician shortage will reach 86,000. This shortage will continue to grow unless sustained and increased investments and policy changes are made to increase the number of trained physicians. Increased investment, which includes a nationwide expansion of the number of available medical residency positions, would represent an important change in helping address these shortages.

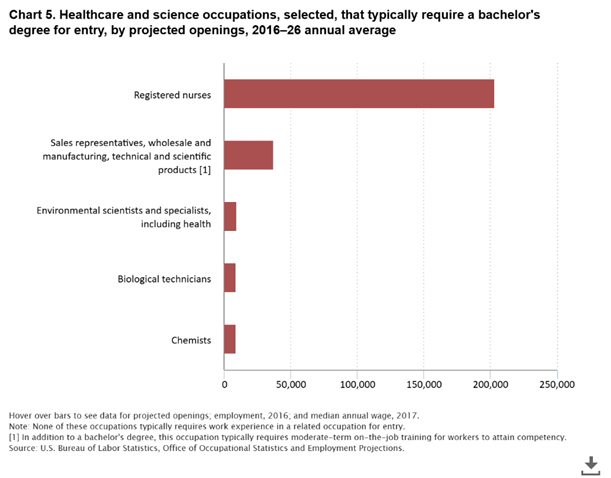

As dire as the physician shortage is shaping up to be, the nursing shortage will likely be worse in terms of sheer numbers, not necessarily in terms of percentage growth. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that, out of all health care and science-related positions, U.S. demand for RN’s will be the largest by far. To meet the growing demand for nurses, the U.S. will need to add an average of more than 200,000 additional RN’s every year to the workforce between 2016-2026.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

In a more recent report, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projected that in the decade between the years 2023 and 2033 the U.S. will need an average of more than 194,500 RN’s every year to meet the growing demand for RN’s.

Other studies also reflect the current state of the nursing shortage. In November 2022, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) projected that there will be a shortfall of 78,610 RNs in 2025, although they forecast a slight decline in the shortage to 63,720 RN’s by 2030. According to that report, the states expected to have the largest shortfalls will be Washington, Georgia, and California.

On the international stage, a report commissioned by the International Council of Nurses (ICN) similarly concluded that the nursing shortage worldwide constitutes “a global health emergency.” The ICN report signals that not only is the U.S. facing its own nursing shortage but is also competing with many other countries to find the nurses it needs.

D. Barriers to Filling the Professional Health Care Demand

That there are shortages of professional health care workers and that it will continue for some time to come has been well established. The ensuing question is what are some of the underlying causes and barriers to addressing these shortage of health care workers.

1. Limited Training Opportunities and Aging Populations

The ongoing physician and surgeon shortage can be attributed to a multitude of factors. Several factors, relate to the limited number of opportunities to study medicine in the U.S., are too few medical schools, too few slots in those schools, too few available internships and residencies. Other factors include governmental underfunding, excessively high costs for students, and the intense multi-year program of study and practice that dissuades some potential students from pursuing this career. This is true not only for general practitioners, but for numerous physician specialties.

At the same time, the aging of the U.S. population, as detailed above, creates more demand for medical care and for a larger health care workforce. In addition, other factors are creating more demand for treatment, including addiction, poverty, and poor nutrition, as well as increased access to health insurance over the past decade, which increases the likelihood that people will pursue medical attention when they need it. This, combined with the growing numbers of physicians and surgeons reaching retirement age (or leaving the profession due to burnout), places major strains on practicing physicians and surgeons. This will have significant consequences even though many doctors increasingly work well beyond retirement age.

The nursing profession faces its own barriers to meeting growing health care demands, including a shortage of nursing school faculty, growing numbers of nurses approaching retirement age, and nurses leaving the profession due to burnout or other factors.

2. The Benefits of Higher Education and Credentialing

Multiple studies over the past two decades, including a 2021 study in in the Nursing Outlook, and a 2003 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), have found a direct correlation between the number of nurses with a bachelor (BSN) or higher, and an increase in the quality of care and a decreased risk of death for patients. In short, higher education among nurses has led to increased quality of care.

Yet a significant group of educated, credentialed people often struggle to find opportunities in the health care workforce – immigrants. For immigrants in particular, one of the biggest barriers to helping address the shortage of physicians and registered nurses is not having their overseas academic credentials and licenses recognized. Credentials and licensing requirements for most occupations are not federally controlled but regulated instead at the state level. These requirements can vary by state and by occupation, with occupational requirements often delegated to state agencies or boards.

Overseas credentials add complexity to this already complicated process, with confusion over other languages and a lack of familiarity with foreign credentials. As a result, skilled, credentialed, and experienced immigrant workers often have to start over to meet U.S. academic and licensing requirements, sometimes forced to enter their fields of expertise at entry-level positions, including in the health care sector.

These barriers often limit immigrant workers from fully contributing in occupations where they already have extensive academic and practical experience. In some instances, immigrant doctors and nurses have been forced to leave the field entirely, taking on jobs in other sectors such as working in retail or serving as taxi or rideshare drivers. While some progress has been made toward addressing these licensing and credentialling barriers, such as for International Medical Graduates (IMGs), much remains to be done to address this “brain waste.”

Access to U.S. higher education is another barrier for immigrants interested in serving as health care professionals, an obstacle that will likely only be heighted after various proposed student visa restrictions are implemented by the Trump administration. But even before any new restrictions, significant hurdles have made it hard for many international students to graduate from U.S. academic institutions or pursue jobs in their expertise. For example, the J-1 visa is the most commonly used visa program for medical students; however, that visa requires students who have completed their academic requirements to return to their country of origin for two years before they are eligible to come back to the U.S. to work as a physician. While the Conrad 30 wavier program allows a limited number of doctors to avoid this requirement, it is capped at a low level and has various stipulations.

The most common visa to study nursing in the U.S. is the F-1 visa program. After completing their studies, nurses can apply for a one-yearOptional Practical Training (OPT) program to gain relevant training as they work, and then pursue an EB-3 green card. However, existing visa caps have generated backlogs with multiyear waits, sometimes representing what is essentially a lifetime wait for certain countries.

III. Recommendations

Given the current shortages of physicians and nurses in the health care workforce-shortages that are only expected to get worse–it is essential that policymakers take steps to address this growing concern. As such, the recommendations that follow focus primarily on immigrant professional health care workers, with some of the recommendations also benefitting others in this sector.

a. Increase Funding for U.S. Residency Programs and Slots

The vast majority of the U.S. residency programs are directly linked to federal funding of the Graduate Medical Education (GME) program. The Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act, a bill that has received significant bipartisan support in the past, would help address the physician shortage. The bill would, incrementally, increase the number of Medicare-supported residency positions each year for seven years, resulting in a total of 14,000 additional positions. The bill had broad bipartisan support, in the 118th Congress (2023-2024) it had a total of 192 House co-sponsors (23 Republicans & 169 Democrats).

b. Increase the Available Conrad-30 Slots for Physicians and Pass the Docter’s Act

As noted above, the Conrad 30 Waiver Program is a small, but beneficial program that allows a small number of immigrants graduating from U.S. medical schools to start their U.S. careers by working in medically underserved communities. Due to the program’s ongoing success, legislation is periodically introduced to reauthorize it, the Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act has garnered broad bipartisan support over the years. As more and more states in the Conrad 30 program are filling all their allocated slots, there is clearly a demand to expand it to allow additional recent graduates to take part.

As a starting point, The DOCTORS Act, a bipartisan and bicameral bill directly linked to the Conrad 30 program, seeks to increase the number of participants in the program by recapturing unused waivers and providing them to states that have maxed out their Conrad 30 slots, increasing the number of international medical students that would be able to work in underserved areas.

Other constructive proposals could authorize the program for longer periods of time and

expand the number of waivers granted to physicians in each state. Additional potential tweaks could exclude participating physicians (and their spouses and children) from the annual cap limits on immigration visas and go further in recapturing prior unused slots.

c. Provide Additional Federal Funding for Compensation to Those Serving Underserved Communities

Proposals to address physician compensation, especially those practicing in underserved communities, can help address workforce shortages. Considering the negative impact of inflation, it is important to ensure that physicians and nurses – immigrant and native-born alike – are compensated properly so they can continue to practice in these areas. Congress can provide additional funding to supplement existing compensation in these communities, making work in these underserved communities more desirable for physicians to practice in.

d. Reintroduce and Pass the Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act

The Healthcare Workforce Resilience Act has drawn significant bipartisan, bicameral support in previous congresses. The bill would respond to the health care worker shortage by recapturing 40,000 unused employment-based visas and use them to expedite processing for immigrant doctors and nurses. The unused visas would be targeted to respond to areas of need and be issued so as not to displace American workers. A constructive and immediate solution to increase access to health care, the bill would provide opportunities to thousands of immigrant health care workers who otherwise might be stuck waiting for years in the green card backlog or otherwise discouraged from practicing in the U.S.

e. Update and Expand “Schedule A”

Shortage Occupation Schedule A is a list of “shortage” occupations in which the Department of Labor (DOL) has determined that hiring foreign workers will not adversely affect the wages or working conditions of U.S. workers. Schedule A shortage occupations are positions in which there are not enough willing, qualified, and available U.S. workers for a sustained period. Those applying for employment-based immigrant visas for Schedule A jobs – which currently includes RNs – do not have to receive a labor certification or an offer of employment. Instead of going through the labor certification process, green card applicants are fast-tracked if they meet certain occupational certification criteria relevant to the position.

DOL very infrequently updates Schedule A occupations, citing concerns about the lack of accurate data. The list was last amended in 2004 but a proposed update to Schedule A in 2024 was introduced, but not finalized and may no longer be under consideration. Given the ongoing shortages of RNs, DOL should modernize and amend the Schedule A list to provide additional places for RNs, and add physicians and surgeons to the Schedule A occupations. Updating Schedule A to include additional health care positions, would represent “an important step” to address labor shortfalls and provide new opportunities to qualified immigrant workers, benefiting patients and health care employers alike.

f. Increase the EB-3 Cap

The EB-3 category is an essential visa for the health care sector, particularly nurses. These visas are capped at 37,520 visas, representing the maximum 26.8 percent of all the employment-based immigrant visas – 140,000 annually, with some adjustments based on unused visas from past years.

It is important to note that the EB-3 visa category, in addition to RNs, covers a broad category of skilled and unskilled workers ranging from house cleaners, construction works, to health care aids, to engineers and lawyers, all of whom must fit into the cap. When looking at the shortage of nurses for 2025 the projection from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is a shortage of 78,610 RNs. Even if all the EB-3 slots went only for RN’s it would not fill even half of what is needed. Given ongoing workforce challenges in health care and elsewhere, Congress should reevaluate the EB-3 cap and increase it to address these needs.

g. Pass the Dream Act or a Similar Dreamer Solution

As noted above, thousands of DACA recipients serve in important health care roles. Yet, legal challenges to DACA and Congress’s failure to provide permanent solutions to Dreamers over a couple of decades threaten to further undermine the health care workforce and deny opportunities to these deserving workers.

The Dream Act was first introduced in Congress in 2001 and remains a needed and bipartisan solution that would give Dreamers, who meet specified requirements, work authorization and a pathway to citizenship. Adopting the Dream Act, or one of a number of other proposed permanent Dreamer solutions, would provide Dreamers with the safety and security to allow more of them the opportunity to pursue careers in the professional health care sector.

IV. Conclusion

Immigrants make invaluable contributions as physicians and registered nurses, filling critical roles in the U.S. health care system. Given ongoing health care workforce shortages, which will only get worse in the years to come, it is important to ensure immigrants can continue to help fill these gaps.

The aging of the U.S. population, the large-scale retirement of Baby Boomers, the retirement or resignation of health care workers, and the extended life expectancies of the general population all contribute to workforce shortages or increase the demand for health care services. Before these challenges become a greater crisis, policymakers should prioritize commonsense immigration solutions to address these workforce challenges, strengthening the U.S health care system, and supporting the health and wellbeing of the American people.

[1] In this paper, the term “physicians” encompasses both physicians and surgeons of many different specialties, following the guidance of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. See “Physicians and Surgeons,” Occupational Outlook Handbook, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physicians-and-surgeons.htm, updated April 18, 2025.

[2] While nurses have many different specialties, educational attainment, and experience levels, this paper will primarily focus registered nurses. Over 70% of registered nurses have a BSN degree or higher. See “Nursing Workforce Fact Sheet,” American Association of Colleges of Nursing, https://www.aacnnursing.org/news-data/fact-sheets/nursing-workforce-fact-sheet, updated April 2024.

The National Immigration Forum would like to thank Cassandra Lis, Policy and Advocacy intern, for helping to develop this paper