Statement for the Record

U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary’s

Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration

Hearing on

“TVPRA and Exploited Loopholes Affecting Unaccompanied Alien Children”

May 23, 2018

The National Immigration Forum (Forum) advocates for the value of immigrants and immigration to the nation. Founded in 1982, the Forum plays a leading role in the national debate about immigration, knitting together innovative alliances across diverse faith, law enforcement, veterans and business constituencies in communities across the country. Leveraging our policy, advocacy and communications expertise, the Forum works for comprehensive immigration reform, sound border security policies, balanced enforcement of immigration laws, and ensuring that new Americans have the opportunities, skills, and status to reach their full potential.

Introduction

The Forum appreciates the opportunity to provide its views on unaccompanied immigrant children (UAC) addressed in the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA), which protects victims of human trafficking. The U.S. asylum system is a long-standing humanitarian effort consistent with our nation’s core value of caring for and protecting the most vulnerable by responding to their situation in compassionate and humane ways. The TVPRA is an important component of that system. We urge Congress to ensure that the United States continues to protect the most vulnerable by enacting laws that welcomes UACs, who flee violence, torture, and persecution in their home countries, and do not enact provisions that would reduce the level of protection they receive.

UACs Are Fleeing Violence

The total number of unaccompanied children attempting to cross the U.S. border has been declining over the last couple of years.[1] In 2017, the number of UACs apprehended along U.S. Southern border dropped 31 percent from FY 2016[2] and the vast majority of U.S. Border Patrol sectors saw overall decreases in apprehensions of those minors.[3] Furthermore, the most recent figures suggest the trend is likely to continue. In the first half of FY 2018, the U.S. Border Patrol apprehended 24 percent fewer UACs compared to the same period in FY 2017.[4] Most of the kids crossing the border without guardians and proper immigration documents came from Guatemala (45 percent in 2015), Honduras (17 percent in 2015), and El Salvador (29 percent in 2015).[5] Moreover, 6 percent were from Mexico and 3 percent from other countries.

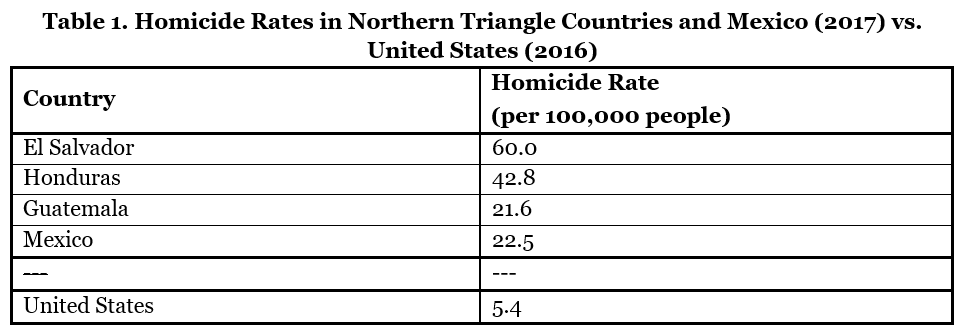

The countries from which UACs are coming are countries that consistently rank[6] among the most violent in the world.[7] Although the rates have fallen in the past few years, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras still have the world’s highest murder rates,[8] and significantly higher homicide rates than neighboring Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama.[9] In 2015, El Salvador became the most violent not-at-war country on the world, as its gang-related violence pushed the country’s murder rate to 103 per 100,000 people.[10] While the number has since fallen considerably, it still remains eleven times higher than that of the United States.[11] In 2017, there were 3,947 murders in El Salvador and the country’s homicide rate stood at 60 per 100,000, down from the 81.2 per 100,000 recorded in 2015. However, a recent survey showed that only 12 percent of Salvadorans believe that crime in the country decreased last year and two thirds of respondents even believe it have increased.[12] Honduras saw 3,791 homicides in 2017 and a murder rate of 42.8 per 100,000 people.[13] Guatemala’s murder rate fell slightly from 27.3 to 26.1 per 100,000 with 4,409 homicides in 2017.[14] Mexico , witnessed over 29,168 homicides in 2017, and the country’s murder rate hit 22.5 per 100,000 inhabitants, its highest murder rate ever.[15] In comparison, the most recent data show that United States recorded 5.4 homicides per 100,000 people in 2016.[16] (Table 1.)

Sources:

Clavel, T. (2018, January 19). InSight Crime’s 2017 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/2017-homicide-round-up/

Crime in the U.S. 2016. (2017, May 08). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016

UACs Need to Be Protected from Gangs

According to Border Patrol data, only a tiny fraction of all unaccompanied youth apprehended have been suspected or confirmed to be associated with gangs such as MS-13.[17] Research finds that UACs are often fleeing violence often caused by gangs in their home countries and persecution.[18] Despite the evidence that UACs are flee violence and persecution, some bills would make it harder for them to enter and stay in the U.S. For example, Senator Heller’s (R-NV) “Criminal Alien Gang Member Removal Act”, or S. 2380, while trying to address the problem of gang violence, could actually weaken protection for UACs. The bill would allow the Secretary of DHS to designate any ongoing group, club, organization, or association of five or more people who, within the last five years, have engaged in at least one of a wide range of offenses as a criminal gang or cartel.[19] It would prohibit those associated with such a group from entering the U.S. if the DHS Secretary, the Attorney General or a consular officer “knows” or “has reason to believe” the individuals are or have been members of a group designated as a criminal gang.[20] Due to the broadness of the bill’s definition of what constitutes a criminal gang or cartel and wide range of applicable offenses, it could impose criminal liability on non-criminal groups. For instance, a church that drives undocumented immigrants to a religious service could be designated a criminal gang or cartel under the bill. In addition, the bill could weaken protections for UACs and other asylum seekers, by blocking individuals merely suspected of belonging to a criminal gang or cartel from entering the U.S. even if they qualify for asylum.[21]

TVPRA Protects Children From Violence and Exploitation

In 2008, Congress passed the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act (TVPRA) with strong bipartisan support. The bill protects victims of human trafficking and includes provisions for unaccompanied children who are often especially vulnerable to trafficking en route to or while in the United States. The protections in the TVPRA for unaccompanied children are consistent with our values and a strong tradition of caring for and protecting the most vulnerable by responding in compassionate and humane ways. However, these protections for unaccompanied children are now at risk, with a number of recent legislative proposals attempting to weaken them.[22]

One of the most important provisions within the TVPRA helps ensure that children are properly assessed for trafficking and asylum claims and not returned to gangs, cartels and other dangers that they were trying to escape, by requiring the officers to undergo specific training to screen the children with sensitivity and care and within adequate time. Further, the act requires U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) to interview all asylum seekers, including UACs, to determine if they face “credible fear” of persecution or torture or of returning to their home countries to determine whether they are eligible to continue the process to seek asylum. [23] Asylum officers refer only individuals found to have “credible fear” or who state they are seeking asylum to immigration court proceedings and an immigration judge decides their eligibility for the protection.

Some recent proposals suggested heightening of these credible fear standards to require asylum officers to seek evidence of such fear in addition to the applicant’s statements. Asylum seekers would have to provide some type of proof of persecution in their countries. Such a change could result in rejecting valid asylum claims and returning people to countries where they face persecution. UACs are especially unlikely to be able to provide proof because they may be too young to understand or explain their situation fully and likely left their homes suddenly without any evidence or preparation on how to present that evidence. This change would also violate the principle of nonrefoulement, the basic international principle that an individual should not be returned to a country in which he or she will face harm of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.[24],

Moreover, the TVPRA directs Customs and Border Protection (CBP) officers to transfer UACs to custody of Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), typically within a 72-hour period after the agency’s screening, for care and further background checks. This requirement puts children in the care of an office that is set up to safeguard their best interest.

The TVPRA directs the State Department to ensure that UACs, who are not eligible to stay in the U.S., are safely repatriated to their country of nationality.[25] The U.S. currently has agreements with our neighboring countries – Mexico and Canada – specifying rules for repatriating unaccompanied children from those two countries. These agreements allow ineligible children to return without additional penalties[26] and guarantee that the children are met by appropriate officials in their country, who will ensure the children’s safety, during reasonable business hours.[27] The U.S. does not have similar agreements with other non-contiguous countries. Therefore, our authorities have very limited control over how the deported children are received after arrival in those countries. Congress should provide financial and other program assistance to Central American countries to ensure the safe repatriation of UACs and encourage the Trump Administration to enter into agreements with other countries similar to those with Mexico and Canada so that we have better information about treatment of UACs after arrival to their home counties.

The TVPRA also requires unaccompanied children from Canada and Mexico – contiguous countries – to be screened within 48 hours of being apprehended to determine whether they should be returned home. For children from other countries (as well as from Mexico and Canada if they are apprehended in the interior) the TVPRA has an additional safeguard, directing asylum officers to transfer these UACs to the care and custody of HHS and place them in formal removal proceedings.[28] Proposals by some in Congress to change the TVPRA so that all Central American children’s asylum claims are processed within 48 hours (as those of children from contiguous countries are processed) would be harmful and contrary to our nation’s value to protect the most vulnerable. By placing them in formal removal proceedings, UACs have more time to adjust to their situation and become more comfortable with sharing information about their circumstances. Hurrying these children’s screening would result in more victims who have viable asylum claims being deported back to danger because children who have been subjected to trauma need more than a few hours to disclose the abuse. Congress should amend the TVPRA to provide these additional protections to all unaccompanied children.

Furthermore, TVPRA requires authorities to place eligible UACs promptly in the “least restrictive setting possible” while awaiting their court hearing.[29] That typically means placement with a parent, relative or other sponsor in the U.S., or alternatively in a shelter or foster home if no sponsor can be found. Proposals to investigate the immigration status of sponsors of UACs and initiate their removal if they are unlawfully present in the U.S. would discourage individuals from sponsoring UACs and increase the psychological strain UACs experience because they would have to stay in ORR custody for longer and be placed in foster care rather than with family. Safe placement of eligible UACs and appropriate treatment of all asylum-seeking children is crucial for their future development.

The TVPRA also allows undocumented children to receive special immigrant juvenile status (SIJS) if reunification with one or both parents is not possible due to abuse, neglect or abandonment[30], and directs immigration authorities to follow special legal procedures for all asylum-seeking children, including access to counsel and child advocates.[31] Some of the recent proposals would require DHS to treat children, who did not qualify as unaccompanied, like adults in immigration removal, stripping them of these special protections for minors. These kids would be required to go through regular proceedings, including apprehension, detention, expedited removal, and mandatory detention. Children are not adults and should not be treated that way. Such an approach could cause serious harm and have long-lasting impact on the children’s physical and mental health, development and wellbeing.

Conclusion

The overwhelming majority of unaccompanied children currently seeking protection in the U.S. are fleeing gangs, violence, and persecution in their home countries. These unaccompanied children are entitled to protection under U.S. and international law.[32] The TVPRA is critical to keeping children safe from violence and exploitation, and we urge Congress to ensure that any amendments to the act will not make UACs more vulnerable to violence and trafficking.

Congress should make the child’s best interest paramount in addressing the situation of UACs. Child safety should not be compromised for the sake of expediency. Congress should enact laws that ensure that the United States continues welcoming unaccompanied children, along with other asylum seekers, and do not limit their protections and rights.

[1] Total Unaccompanied Alien Children (0-17 Years Old) Apprehensions By Month, FY10-FY17. (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2017-Dec/BP Total Monthly UACs by Sector, FY10-FY17.pdf

[2] U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2017. (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions-fy2017

[3] U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2017. (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions-fy2017

[4] U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions

[5] Factsheet: U.S. Department of Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Refugee Resettlement, Unaccompanied Children’s Program (Rep.). (2016, January). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Administration for Children and Families website: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/orr/orr_uc_updated_fact_sheet_1416.pdf

[6] Labrador, R. C., & Renwick, D. (2018, January 18). Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Council On Foreign Relations website: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle

[7] Gagne, D. (2017, January 16). InSight Crime’s 2016 Homicide Round-up(Rep.). Retrieved https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2016-homicide-round-up/

[8] Labrador, R. C., & Renwick, D. (2018, January 18). Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Council On Foreign Relations website: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle

[9] Labrador, R. C., & Renwick, D. (2018, January 18). Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Council On Foreign Relations website: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle

[10] El Salvador gang violence pushes murder rate to postwar record. (2015, September 2). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/el-salvador-gang-violence-murder-rate-record

[11] Labrador, R. C., & Renwick, D. (2018, January 18). Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle (Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Council On Foreign Relations website: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle

[12] Clavel, T. (2018, January 19). InSight Crime’s 2017 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/2017-homicide-round-up/

[13] Clavel, T. (2018, January 19). InSight Crime’s 2017 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/2017-homicide-round-up/

[14] Clavel, T. (2018, January 19). InSight Crime’s 2017 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/2017-homicide-round-up/

[15] Clavel, T. (2018, January 19). InSight Crime’s 2017 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/2017-homicide-round-up/

[16] Crime in the U.S. 2016. (2017, May 08). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016

[17] Fact Sheet: Immigrant Youth and MS-13. (2017, December 12). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from https://leitf.org/2017/12/fact-sheet-immigrant-youth-ms-13/#_ftn10

[18] Kandel, W. A. (2017, January 18). Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43599.pdf

[19] S.2380 – Criminal Alien Gang Member Removal Act. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2380

[20] Penichet-Paul, C. (2018, February 27). Building America’s Trust Act: Bill Summary(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from National Immigration Forum website: https://forumtogether.org/article/building-americas-trust-act-bill-summary/

[21] Penichet-Paul, C. (2018, February 27). Building America’s Trust Act: Bill Summary(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from National Immigration Forum website: https://forumtogether.org/article/building-americas-trust-act-bill-summary/

[22] Cepla, Z. (2018, March 23). Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act Safeguards Children(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from National Immigration Forum website: https://forumtogether.org/article/trafficking-victims-protection-reauthorization-act-safeguards-children-2/

[23] Unaccompanied Alien Children: A Primer(Rep.). (2014, July 21). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Bipartisan Policy Center website: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/unaccompanied-alien-children-primer/

[24] Advisory Opinion on the Extraterritorial Application of Non-Refoulement Obligations under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol(Rep.). (2007, January 26). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) website: http://www.unhcr.org/4d9486929.pdf

[25] A Guide to Children Arriving at the Border: Laws, Policies and Responses(Rep.). (2015, June 26). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from American Immigration Council website: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/guide-children-arriving-border-laws-policies-and-responses

[26] Kandel, W. A. (2017, January 18). Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43599.pdf

[27] Unaccompanied Alien Children: A Primer(Rep.). (2014, July 21). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Bipartisan Policy Center website: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/unaccompanied-alien-children-primer/

[28] Kandel, W. A. (2017, January 18). Unaccompanied Alien Children: An Overview(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/homesec/R43599.pdf

[29] Unaccompanied Alien Children: A Primer(Rep.). (2014, July 21). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from Bipartisan Policy Center website: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/unaccompanied-alien-children-primer/

[30] Richardson, H., Blumenfeld, M., & Vannucci, K. M. (2017, January). USCIS Policy Updates for Special Immigrant Juveniles: A Practice Advisory for State Court Practitioners(Rep.). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from National Immigrant Justice Center website: https://www.immigrantjustice.org/sites/default/files/content-type/resource/documents/2017-01/USCIS Policy Updates SIJS Practice Advisory.1.12.17.pdf

[31] A Guide to Children Arriving at the Border: Laws, Policies and Responses(Rep.). (2015, June 26). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from American Immigration Council website: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/guide-children-arriving-border-laws-policies-and-responses

[32] Children on the Run: Unaccompanied Children Leaving Central America and Mexico and the need for International Protection(Rep.). (2014, March 13). Retrieved May 22, 2018, from UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) website: http://www.refworld.org/docid/532180c24.html