Introduction

The National Immigration Forum appreciates the opportunity to provide its views on the benefits of immigration in building a more dynamic economy. U.S. economic growth is outpacing growth in workers. As a result, labor shortages are projected to grow that will act as a brake on the economy. We are already seeing inflationary fears stoked by labor shortages, and in some regions of the U.S., businesses are postponing plans for expansion due to lack of workers.

The crucial role immigrants play in our workforce and economy is unfamiliar to many people. Immigrants currently represent about 13 percent of the population but 17 percent of the U.S. workforce. Immigrants are projected to provide the bulk of growth in our workforce in the coming 40 years.

Founded in 1982, the National Immigration Forum advocates for the value of immigrants and immigration to our nation. To achieve this vision, we bring together moderate and conservative faith, law enforcement and business leaders to weigh in with policy makers in support of practical and commonsense immigration, citizenship and integration policies.

Our current immigration system fails to meet the needs of the nation’s economy, workforce and families. Congress and the administration must work together to build a 21st-century immigration system that advances the social and economic interests of all Americans.

Immigrants are a net benefit to our economy.

The U.S. economy is stronger because of immigrants. In 2014, immigrants earned a total of $1.3 trillion in wages, or 14.2 percent of all income earned in the United States.[1] The percentage of income earned is greater than the percentage of immigrants in the general population (13.2 percent). This disparity, in part, occurs because a greater percentage of immigrants are in their working and income-earning years than the U.S. born.

The total spending power of immigrants in the U.S. – the total income they earn minus the taxes they pay – was $927 billion in 2014, or more than 14 percent of the total American spending power.[2] The spending power of refugees in the U.S. was estimated to be $56 billion in 2015.[3] Much of this revenue goes back into the economy, creating demand for goods and services, which, in turn, help create jobs.

Regardless of their immigration status, immigrants pay taxes and spend money in local economies. Without these important economic contributions from immigrants, the U.S. economy would be smaller, and governments at all levels would see revenues decline without the taxes paid by immigrants. Research analysts have examined the economic contributions of immigrants and have concluded that, when looking at the taxes paid by immigrants verses the cost of services provided to them, immigrants have a significant positive balance. This time period includes the cost and contributions of their children. While local governments bear the cost of educating immigrant children, education is an investment, yielding higher returns in terms of income earned and taxes paid.

The net fiscal contribution of a new immigrant and immigrant’s children over a 75-year period considering the cost of services to immigrants compared to how much immigrants pay in taxes is positive.[4] The average benefit to all levels of government is $259,000. An immigrant with a college degree contributes more during that same period, approximately $800,000.

Refugees are also a positive net benefit to the U.S. economy. A recent government study estimated that, in the ten-year period between 2005 and 2014, total government expenditures on refugees were $206 billion, but in the same period refugees paid federal, state and local taxes of $269 billion.[5] A study by the New American Economy estimated that refugees earned $77 billion and paid $20.9 billion in taxes in 2015 alone.[6]

In recent years, the net economic contributions of immigrants has increased in tandem with the rising education levels of recent immigrants. A recent analysis of U.S. Census data has found that almost half of the immigrants coming to the U.S. between 2011 and 2015 were college graduates. This compares to 27 percent of immigrants who arrived from 1986-1990.[7] As a result, the fiscal benefit of recently arrived immigrants over a 75-year period is much higher than that of all U.S. immigrants, past and present.[8] The average fiscal benefit was $259,000 for recent immigrants, while the average fiscal benefit for all immigrants was $58,000. The trend toward higher education levels in our immigration flows is expected to continue or intensify, ensuring that immigrants will continue to be a fiscal boon for our country. Immigrants have helped make the American economy the strongest in the world.

Immigrants are tax contributors.

Immigrants pay the same taxes we all do — federal income tax, social security tax, Medicare tax, property tax, state income tax, sales tax, and so on. The taxes they pay help to cover federal and state services that benefit communities everywhere. In 2014, immigrants paid an estimated $328 billion in state, local, and federal taxes. Immigrants paid more than a quarter of all taxes in California, and they paid nearly a quarter of all taxes in New York and New Jersey.[9]

It is not only immigrants, who are legally present in the U.S., who are paying taxes. Undocumented immigrants make important contributions as well. An analysis based on the U.S. Census and other data estimated that undocumented immigrants paid $11.7 billion in state and local taxes. If they had a pathway to secure legal status, they would likely earn more and, consequently, more of their income would be on the books. Their state and local tax contributions would increase accordingly, by an estimated $2.2 billion.[10]

Young undocumented immigrants who grew up in the United States and are participants of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA) currently have permission to work legally in the U.S. The vast majority, approximately 91 percent, are currently employed.[11] They pay an estimated $1.6 billion in state and local taxes.[12] If DACA holders were no longer able to work, states and localities would collectively face a loss of almost $800 million in tax revenue because DACA holders incomes would drop, and more of it would be “off the books.” On the other hand, if Congress provides a path to citizenship for these individuals, states and localities would see their revenue boosted by about $50 million.

Immigrants contribute to the economy as business owners.

In addition to contributing to the economy as taxpayers and consumers, immigrants contribute to the economy as business owners. Immigrants are much more likely to start businesses than the U.S.-born. Of all new entrepreneurs in 2016, 29.5 percent were immigrants.[13] More than 20 percent of new and established business owners in the U.S. were immigrants in 2014.[14] This representation is far above the immigrant community’s 13.2 percent of the U.S. population.[15]

Immigrants have founded 51 percent of the country’s startup companies worth $1 billion or more as of January 1, 2015, a study conducted in 2016 found. Each of these companies employed an average of 760 people.[16]

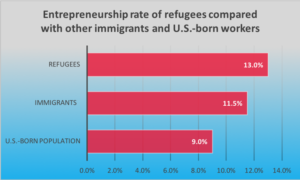

Refugees have an even higher rate of entrepreneurship. Thirteen percent of refugees are business owners, compared to 11.5 percent of non-refugee immigrants. Refugee-owned businesses generated $4.6 billion in income in 2015.[17]

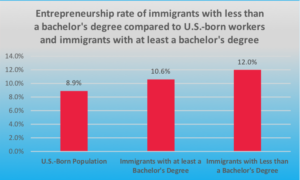

The rate of entrepreneurship among immigrants with less than a college degree is actually higher than that of immigrants with college degrees; 12 percent of immigrants without college degrees are entrepreneurs compared to 10.6 percent of those with college degrees.[18] Both groups have a greater tendency to be entrepreneurs than U.S.-born workers, who make up 8.9 percent of self-employed entrepreneurs.

Immigrant businesses revive neighborhoods and spur economic development.

Immigrant-owned businesses like other businesses can revitalized and spur economic development in local communities. A report, which closely examined the types of businesses immigrants tended to own by using data from 2013, found that 28 percent of “Main Street” business owners were immigrant entrepreneurs.[19] “Main Street” businesses can be broken into three categories: Retail (such as florists, grocery stores), Accommodation and Food Services (restaurants, hotels) and Neighborhood Services (barbers, dry cleaners). These “Main Street” businesses are often the seed of economic development in an area that has been neglected. They can transform a neighborhood into a more attractive area, where people can live and work, thus sparking greater economic activity. Immigrant entrepreneurs make up more than 50 percent of business owners in some of these “Main Street” subcategories.[20] These small and medium-sized immigrant businesses are often undervalued when local governments are considering the best ways to revitalize their localities.

Around the country, city and state leaders are realizing that attracting immigrant entrepreneurs is a crucial piece of an economic development strategy. A report from Global Detroit notes that “…city leaders are realizing that immigrant groups stabilize residential neighborhoods and commercial retail corridors that are critical to the quality of life.”[21] Immigrants in Michigan were nearly three times more likely to start businesses between 1996 and 2007 than were native-born residents. Detroit leaders have launched several initiatives to attract and retain immigrants and promote immigrant entrepreneurship.[22]

Not only major cities seek to attract immigrant entrepreneurs to revitalize neighborhoods. For example, small towns in Iowa are working with Iowa State University to promote immigrant entrepreneurship and integration as part of their economic development strategy.[23]

Businesses started by immigrant entrepreneurs create millions of jobs and generate billions of dollars in revenue. Immigrant entrepreneurs are not only providing for themselves and their families, but are helping revitalize neighborhoods, cities and regions that have seen economic decline. These investments by immigrants benefit everyone in the community.

Immigrants fill labor shortages helping the economy grow.

According to the Census Bureau, there are 161 million workers in the American workforce.[24] Immigrants make up approximately 17 percent of the U.S. labor force, about one in six workers.

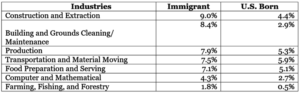

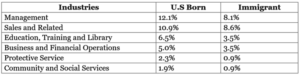

Focusing on the makeup of the workers in different industries, shows that certain industries are very reliant on immigrant labor.[25] While only 9 percent of immigrants work in construction, immigrants make up nearly a quarter (24.1 percent) of the construction workforce. Other examples are represented in the graph below.

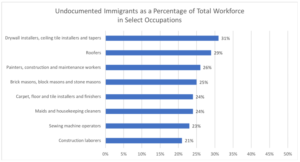

Undocumented workers are a crucial component of many occupations as well. The graph below highlights some of the occupations where undocumented immigrants are estimated to make up a significant percentage of workers.[26]

Immigrants complement workforce needs. An immigrant filling a job does not mean a U.S.-born worker loses a job. Economists find that the economy is dynamic and the number of jobs is not set. When one person takes a job, other jobs are created. That newly employed person spends money on groceries, goes out to eat, buys clothing, and that extra demand for goods and services creates new jobs for other workers.

U.S.-born and immigrant workers are employed in disparate jobs within our workforce. Seven industry categories employ nearly half (46.1 percent) of immigrant workers, but only a little more than a quarter (26.7 percent) of U.S. born workers.[27]

A different set of industry categories employ more than half (51.6 percent) of the U.S.-born workers, but only a third (33.6 percent) of immigrant workers.[28]

Immigrants and their children will drive workforce growth.

According to the latest population projections by the U.S. Census Bureau, immigration will become the primary driver of U.S. population growth by 2030, not because of an increase in immigration, but primarily due to the — rising number of deaths and lower birth rates in the U.S.-born population.[29] This growth in the workforce is critical to our economy.

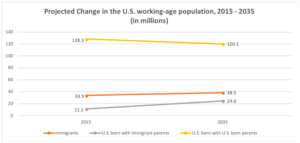

Growth in the country’s workforce likewise will be driven by an increase in the number of immigrant workers between now and 2035. As the baby boom generation leaves the workforce, the number of working-age adults born in the United States to U.S.-born parents will decline by 8.2 million. Balancing out this decline will be the growth in the number of working-age immigrants and their children. [30] Without new immigrants, the total population of working-age adults is expected to decline over the next 20 years.

The government projects the economy will add 9.8 million jobs between 2014 and 2024, but the labor force will only grow by 7.9 million workers.[31] In other words, the economy will grow faster than the workforce will. However, if more restrictive immigration policies are put in place, this gap between job openings and available workers will grow. If immigration to the United States is reduced, the working-age population will grow more slowly, or not at all. Restricting legal immigration to the U.S. will act as a brake on the economy, slowing its growth.

The U.S. is not unique in the demographic challenges it faces in regards to a growing shortage in workers and a society that is aging overall. An extreme example is Japan, a low-immigration and highly automated society, where more than one quarter of the population is 65 or older.[32] That country periodically slips into recession because it is running out of workers.[33] While its economy has improved in recent years, labor shortages have become extreme, with 71 percent of firms reporting manpower shortages.[34] Labor shortages have translated into deteriorating services in parcel delivery, hospitals, restaurants, schools and other labor-intensive services.[35] The Japanese government has come to the realization that it must have immigrant workers to ease its labor shortages, and has taken tentative steps to ease its traditional aversion to immigration.[36]

Italy already has a negative growth rate, and 0ther countries like the United Kingdom, Spain, Singapore, South Korea and China all face similar problems.[37] The point being, immigrant workers will be a highly competitive resource, with immigrants weighing their options as to the best place to work. Immigrants will be a major contributor to the economic health of many countries, including the U.S.

Immigration will not entirely solve the labor shortages, but immigrants can help address the problem. In order for that to happen, we must update our laws to allow for appropriate legal channels for immigrants to come to the U.S. and work. We must address the unique workforce challenges of immigrant workers. The number of foreigners allowed to come to the U.S. as permanent or temporary workers must increase as it is capped at the same level as it was in 1990 when our economy was one-third the size it is now.

Another immigration-related challenge is looming for the American workforce, the Trump administration has moved to end two programs that have allowed hundreds of thousands of immigrants to stay here temporarily and work with proper work authorization.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) has protected more than 800,000 people who arrived in the U.S. as children, and have lived hear practically all of their lives. One analysis of the DACA-eligible population — which includes all those eligible, not just the 800,000 who have actually registered and gained work authorization — shows that more than 155,000 are employed in restaurants and other food services, nearly 85,000 are employed in the construction industry, and more than 17,000 are employed in hospitals.[38]

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) is the other program being cut and is available to persons in the U.S. who cannot safely return to their country because of natural disaster, armed conflict, or similar calamity. Recipients of TPS receive work authorization. TPS designations for some countries have been repeatedly extended, and some recipients of TPS have had been in the U.S. and working for many years.

Cuts to legal immigration and an invisible wall of rules and regulations is being built that is cutting our future workforce. Immigration is projected to be the main component of growth in the U.S. working-age population in the coming decades.[39] In addition, while choosing immigrants based on education attainment sounds good in principle, it will not match our immigration system to the needs of the American workforce. The U.S. economy needs workers across the skills spectrum. Between 2014 and 2024, eight of the top 15 job categories that will see the greatest growth will require no formal educational credential[40]. Jobs such as personal care aides, home health aides, food preparation workers, retail salespersons, cooks, construction laborers, janitors, and material movers are expected to increase by 2,032,000 in the 10-year period from 17,537,000 jobs to 19,569,000 jobs, representing 21 percent of all new jobs.

Conclusion

The U.S. economy has benefited from immigrants in countless ways, entrepreneurship, taxes, spending power, filling temporary and permanent position across the entire skills spectrum, and revitalizing local economies. Immigrants are and will be the growth factor in the U.S. economy. The economy is in search of workers and the demand outstrips the availability. There simply are not enough workers. These challenges are already negatively affecting certain industries and regional economies, and they are only going to grow in light of our aging population and the declining native birth rate. Immigrants and their children are helping to address this crisis, but a far more responsive workforce development and immigration system must be enacted to create a dynamic economy, or the growth of the U.S. economy will begin to slow and decline altogether.

[1] “Taxes and Spending Power,” New American Economy, https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/issues/taxes-&-spending-power/.

[2] “Immigrants’ Impacts on Fiscal Matters,” Tax Policy Center, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/immigrants_impact_on_fiscal_matters_fact_sheet.pdf.

[3] “From Struggle to Resilience: The Economic Impact of Refugees in America,” New American Economy, June 19, 2017, https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/from-struggle-to-resilience-the-economic-impact-of-refugees-in-america/

[4] “Immigrants’ Impacts on Fiscal Matters,” Tax Policy Center, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/immigrants_impact_on_fiscal_matters_fact_sheet.pdf.

[5] “Rejected Report Shows Revenue Brought in by Refugees,” The New York Times, September 19, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/19/us/politics/document-Refugee-Report.html.

[6] “From Struggle to Resilience: The Economic Impact of Refugees in America,” New American Economy, June 19, 2017, https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/from-struggle-to-resilience-the-economic-impact-of-refugees-in-america/.

[7] Jeanne Batalova and Michael Fix, “New Brain Gain: Rising Human Capital Among Recent Immigrants to the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, June 2017, https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/new-brain-gain-rising-human-capital-among-recent-immigrants-united-states.

[8] Pia Orrenius, “New Findings on the Fiscal Impact of Immigration in the United States,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, https://www.dallasfed.org/en/research/papers/2017/wp1704.aspx.

[9] “Taxes and Spending Power,” New American Economy, https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/issues/taxes-&-spending-power/.

[10] “Immigrants in the United States,” American Immigration Council https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/immigrants-in-the-united-states

[11] Tom K. Wont et al., “DACA Recipients’ Economic and Educational Gains Continue to Grow,” Center for American Progress, August 28, 2017, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2017/08/28/437956/daca-recipients-economic-educational-gains-continue-grow/.

[12] Meg Wiehe and Misha Hill, “State and Local Tax Contributions of Young Undocumented Immigrants,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 30, 2018. https://itep.org/state-local-tax-contributions-of-young-undocumented-immigrants/.

[13] “Startup Activity National Trends,” The Kauffman Index, May 2017, https://www.kauffman.org/kauffman-index/reporting/~/media/c9831094536646528ab012dcbd1f83be.ashx.

[14] “Reasons for Reform: Entrepreneurship,” New American Economy, October 2016, http://www.newamericaneconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Entrepreneur.pdf

[15] “Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates,” The United States Census Bureau, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

[16] Stuart Anderson, “Immigrants and Billion Dollar Startups,” National Foundation for American Policy, March 2016, http://nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Immigrants-and-Billion-Dollar-Startups.NFAP-Policy-Brief.March-2016.pdf.

[17] “From Struggle to Resilience: The Economic Impact of Refugees in America,” New American Economy, June 2017. research.newamericaneconomy.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/11/NAE_Refugees_V6.pdf.

[18] “One Cost of Cutting Back in Less-Skilled Immigration: Potential Business Creation,” New American Economy, August 10, 2017, https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/one-cost-of-cutting-back-on-less-skilled-immigration-potential-business-creation/.

[19] David Dysseggard Kallick, “Bringing Vitality to Main Street: How Immigrant Small Businesses Help Local Economies Grow,” Americas Society/Council of the Americas, January 2015, www.as-coa.org/sites/default/files/ImmigrantBusinessReport.pdf.

[20] David Dysseggard Kallick, “Bringing Vitality to Main Street: How Immigrant Small Businesses Help Local Economies Grow,” Americas Society/Council of the Americas, January 2015, www.as-coa.org/sites/default/files/ImmigrantBusinessReport.pdf.

[21] Steve Tobocman, Global Detroit, May 14, 2010, www.globaldetroit.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Global_Detroit_Study.executive_summary.pdf.

[22] Paul McDaniel, “Revitalization in the Heartland of America: Welcoming Immigrant Entrepreneurs for Economic Development,” Immigration Policy Center, January 2014, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/revitalizationinheartlandofamerica.pdf

[23] Paul McDaniel, “Revitalization in the Heartland of America: Welcoming Immigrant Entrepreneurs for Economic Development,” Immigration Policy Center, January 2014, https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/research/revitalizationinheartlandofamerica.pdf

[24] “Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates,” The United States Census Bureau, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

[25] “Selected Characteristics of the Native and Foreign-Born Populations 2012-2016 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates,” The United States Census Bureau, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk.

[26] Jeffrey S. Passel and D’Vera Cohn, “Size of U.S. Unauthorized Immigrant Workforce Stable after the Great Recession,” Pew Research Center, November 3, 2018, assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2016/11/02160338/LaborForce2016_FINAL_11.2.16-1.pdf.

[27] Kenneth Megan and Theresa Cardinal Brown, “Culprit or Scapegoat? Immigration’s effect on Employment and Wages,” Bipartisan Policy Center, June 2016, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/BPC-Immigration-Employment-and-Wages.pdf.

[28] Kenneth Megan and Theresa Cardinal Brown, “Culprit or Scapegoat? Immigration’s effect on Employment and Wages,” Bipartisan Policy Center, June 2016, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/BPC-Immigration-Employment-and-Wages.pdf.

[29] Jonathan Vespa, David M. Armstrong, and Lauren Medina, “Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060,” United States Census Bureau, March 2018, https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2018/demo/P25_1144.pdf.

[30] Jeffrey S. Passel and D’Vera Cohn, “Immigration Projected to Drive Growth in U.S. Working-Age Population Through at Least 2035,” Pew Research Center, June 12, 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/08/immigration-projected-to-drive-growth-in-u-s-working-age-population-through-at-least-2035/.

[31] “Occupational Employment Projections to 2024,”United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2015, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/occupational-employment-projections-to-2024.htm.

[32] Keiko Ujikane, Katsuyo Kuwako and Jodi Schneider, “60 seen as too young to retire in aging, worker-short Japan,” Japan Times, July 15, 2016, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/07/15/national/60-seen-young-retire-aging-worker-short-japan/#.XE92Oi2ZNBy.

[33] Matthew Yglesias, “The real reason Japan’s economy keeps stumbling into recession,” Vox, November 17, 2017, https://www.vox.com/2015/11/17/9749264/japan-recession-abenomics.

[34] “70% of firms pinched by labor shortages, Finance Ministry survey says,” Japan Times, February 1, 2018, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/02/01/business/70-firms-pinched-labor-shortages-finance-ministry-survey-says/#.XE93xS2ZNBx.

[35] Masayuki Morikawa, “Hidden inflation: Japan’s labour shortage and the erosion of the quality of services,” Vox CEPR Policy Portal, March 31, 2018, https://voxeu.org/article/japan-s-labour-shortage-beginning-erode-quality-services.

[36] “Japan faces challenges as it moves to accept more foreign workers,” Japan Times, July 25, 2018, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2018/07/25/national/japan-faces-challenges-moves-accept-foreign-workers/#.XE945C2ZNBx.

[37] Peter Kotecki, “10 countries at risk of becoming demographic time bombs,” Business Insider August 8, 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/10-countries-at-risk-of-becoming-demographic-time-bombs-2018-8.

[38] “Spotlight on the DACA-Eligible Population,” New American Economy, Updated February 8th, 2018, https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/spotlight-on-the-daca-eligible-population/.

[39] Jeffrey Passel and D’Vera Cohn, “Immigration projected to drive growth in U.S. working-age population through at least 2035,” Fact Tank, Pew Research Center, March 8, 2017, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/08/immigration-projected-to-drive-growth-in-u-s-working-age-population-through-at-least-2035/.

[40] “Occupational Employment Projections to 2024,”United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics, December 2015, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2015/article/occupational-employment-projections-to-2024.htm.

Author: Dan Kosten