Statement for the Record

U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee

Subcommittee on Border Security and Immigration

Hearing on

“At the Breaking Point: The Humanitarian and Security Crisis at our Southern Border”

May 8, 2019

Introduction

The National Immigration Forum appreciates the opportunity to provide its views on addressing the situation at the U.S. Southern border. Since January 2019, an increasing number of migrants from Central America are being apprehended at our Southern border, including an increase in the number of family units seeking asylum.[1] The situation calls for re-examining the effectiveness of the federal government’s current policies and for a dialogue on implementing a new strategy to address the migrants at the border that ensures our laws are being followed while we continue to treat those seeking humanitarian assistance with compassion. We urge Congress to ensure that the United States continues to protect the most vulnerable by enacting laws that welcome migrants who flee violence, torture, and persecution, and work with other governments and organizations outside the U.S. on implementing policies that would reduce the power of push factors that drive individuals out of their home countries.

More Families and Children Are Arriving at U.S. Border

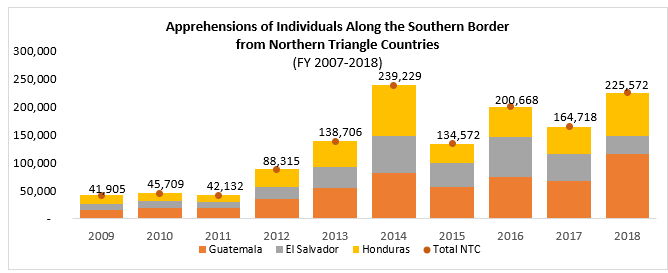

While the number of migrants trying to cross the Southern border between ports of entry has remained relatively stable during the past ten years at around 400,000,[2] the demographic make-up of those migrants has changed considerably with migrants from the Northern Triangle Countries (NTCs) of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala accounting for a considerable share of the total since 2014.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector FY 2007-2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf

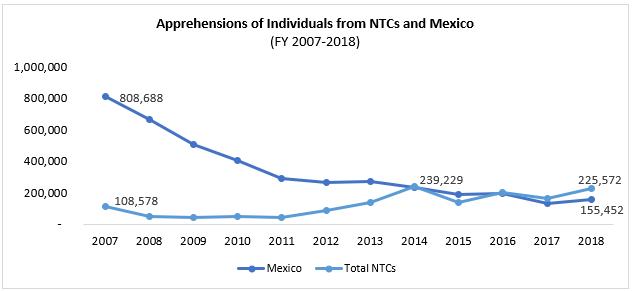

Until recently, the largest number of migrants entering the country between ports of entry (POEs) were from Mexico. However, this trend began to change in 2014. Since 2016, the number of migrants from NTCs has exceeded the number of Mexican migrants.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector FY 2007-2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector FY 2007-2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf

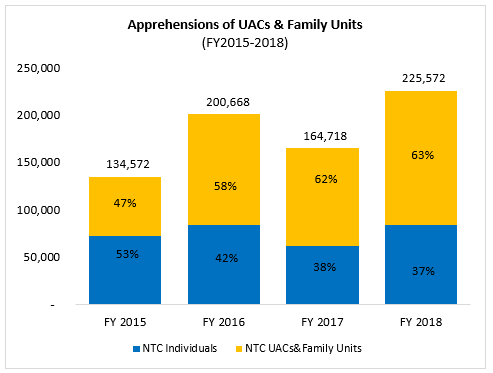

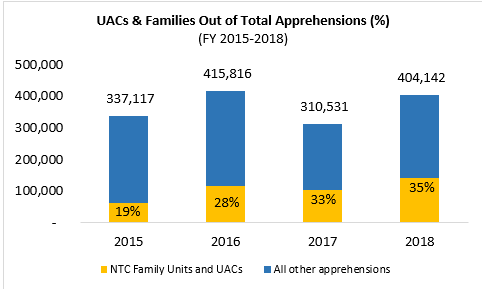

Moreover, an increasing number of NTC migrants apprehended along the Southern border in the last few years have been children and families. Between fiscal years (FY) 2015 and 2018, the proportion of family units and unaccompanied children (UACs) apprehended at the Southern border increased substantially, accounting for 63 percent of all apprehensions of NTC migrants in FY 2018. Overall, unaccompanied children and families have accounted for an increasing share of NTC migrants as well as an increasing share of the total number of all migrants overall that attempted to enter the U.S. between POEs from FY 2015 through FY 2018.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions ; U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children Statistics FY 2016. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/site-page/southwest-border-unaccompanied-alien-children-statistics-fy-2016

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions ; U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children Statistics FY 2016. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/site-page/southwest-border-unaccompanied-alien-children-statistics-fy-2016

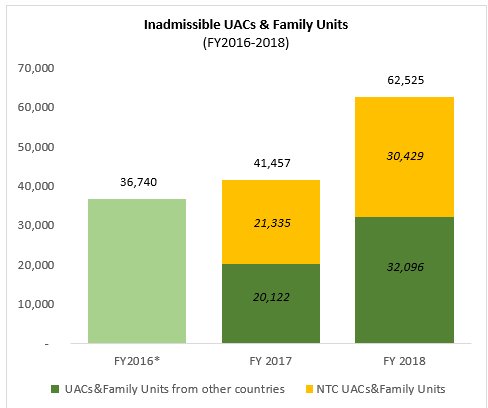

Since FY 2017, an increasing number of families and UACs from NTCs have been presenting themselves at one of the ports of entry to seek asylum. In FY 2017 and FY 2018, children and families from NTCs accounted for about a half of all UACs and family units that presented themselves to the Border Patrol officers along the Southern border.

*By-country breakdown data for 2016 is not available

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles ; U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2017. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles-fy2017

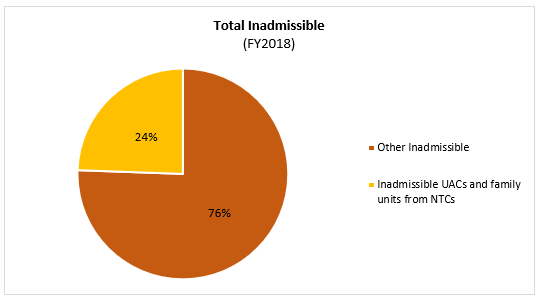

In FY 2018, UACs and families from NTCs accounted for about a quarter of all inadmissible individuals who arrived at one of the POEs along the Southern border.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles ; U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2017. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles-fy2017

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles ; U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2017. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles-fy2017

In 2019, more families and UACs from NTCs have been continuing to arrive at the U.S. Southern border. As of March 2019, 74 percent of all migrants apprehended at the border were from one of the NTCs and 58 percent were families or UACs from one of the NTCs.[3]

Migrants Are Fleeing Violence and Poverty

The “Northern Triangle Countries” of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras share political, social, and economic similarities, including high crime rates, pervasive gang violence, extreme poverty and corruption[4], which all play a crucial role in migrants’ decision to leave.

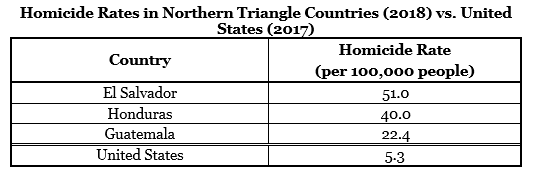

All three NTCs rank among the most violent countries in the world, with significantly higher murder rates than neighboring Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Panama. [5] In 2015, El Salvador became the most violent country in the world that is not at war, [6] with gang-related violence pushing the country’s murder rate to 103 per 100,000 people.[7] While that number has since fallen considerably to 51 per 100,000 in 2018, representing 3,340 murders,[8] it still remains nearly ten times higher than that of the United States.[9]

Similarly, Honduras saw 3,310 homicides in 2018 and a murder rate of 40 per 100,000 people.[10] Guatemala’s 3,881 homicides in 2018 represented a murder rate of 22.4 per 100,000, a reduction from recent years.[11] In comparison, the most recent data show that United States recorded 5.3 homicides per 100,000 people in 2017.[12]

Gang activity is one of the main factors consistently driving the homicide rates in NTCs,[13] disproportionately affecting poor communities that are targeted by gangs for membership recruitment and extortion.[14] Gang activity, along with ineffectual responses by NTC governments, creates a self-perpetuating cycle of lawlessness and violence. Organized crime groups target small businesses and poor neighborhoods to recruit members to assist in or pay “protection,” threatening and harming individuals who do not comply with their demands. The imminent and omnipresent nature of oppressive gang activity forces innocent people to live under the constant threat of violence. A survey conducted by Doctors Without Borders of nearly 500 NTC migrants, found that almost 40 percent mentioned direct attacks or threats to themselves or their families, extortion, or gang-forced recruitment as the main reason for fleeing their countries, with 43.5 percent reporting that they had a relative who died due to violence in the previous two years.[15] Additionally, a recent Congressional Research Services (CRS) study showed that Salvadorian and Honduran victims of crimes are 10 to 15 percent more likely to migrate than those who have not had such an experience.[16]

Moreover, large numbers of people in the NTCs live in poverty, which makes them more likely to be victimized by gangs that use their socioeconomic vulnerability to manipulate them.[17] Over 66 percent of Hondurans lived in poverty in 2016.[18] Guatemala has faced some of the worst poverty levels (around 60 percent[19]) in Latin America.[20] El Salvador’s poverty rate hit 31 percent in 2016.[21] Gangs profit off rising poverty levels by ramping up recruitment efforts in poor communities, increasing their control over the government and society. The vicious cycle is spurred even more by ineffectual governments, which are unwilling or unable to help their most vulnerable citizens.

In addition to violence and corruption, climate change-induced environmental threats also “push” NTC migrants to leave their home countries. The WorldRiskIndex, a measure conducted by Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft and International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV) at Ruhr-University Bochum that examines the disaster risk for 172 countries worldwide, revealed Guatemala and El Salvador are among the 15 countries most prone to natural disasters, such as earthquakes and droughts.[22] Since about 25 percent of the countries’ workforces are employed in the agriculture sector,[23] changing climate and natural disasters impact heavily the populations’ wellbeing.

In 2015, a massive drought plagued the NTCs, leading to financial disaster for farmers and resulting in a food shortage that had the most devastating impact on impoverished communities.[24] Individuals who were already fearful of gang violence became even more motivated to leave their countries because the drought caused food insecurity. In the most heavily-impacted areas, migrants cited “no food” as the main reason for leaving their country.[25] Guatemala has one of the highest food insecurity and malnutrition rates in Latin America, with nearly 1 million Guatemalans suffering from moderate to severe food insecurity.[26] In 2018, the International Food Policy Research Institute’s Global Hunger Index,[27] a measure that tracks hunger at global, regional, and national levels, determined that Guatemala and Honduras had the second and third highest hunger levels in Central America and the Caribbean, after first-ranked Haiti.

We Cannot Enforce Our Way into a Solution

Congress must focus on solutions that address the situation of migrants at the Southern border, not just on enforcement. Indeed, Congress has already taken strides to make the border more secure. Following the passage of the Secure Fence Act[28] in 2006, the U.S. built nearly 700 miles[29] of physical barriers along the 2,000-mile Southwest border, an all-time high, with the rugged terrain and the Rio Grande acting as natural barriers in other areas. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) also relies heavily on technology to secure the Southwest border, including fixed towers, mobile surveillance systems, and ground sensors. To complement these physical barriers and technology, the Border Patrol stationed 16,608 agents[30] in the Southwest border region in fiscal year (FY) 2018 – the latest figures available – nearly double the number in FY 2000. In addition, between FY 2000 and FY 2017, Congress increased the Border Patrol’s budget approximately 380 percent[31] from about $1.1 billion to nearly $3.8 billion. At this point, America’s Southwest border has never been more secure. Building more fencing and ramping up enforcement in the border region will only provide limited returns, doing little to discourage migrants escaping violence who seek out Border Patrol personnel upon entry to claim asylum.

Without addressing push factors in Central America, enforcement-focused policies have failed to deter migrants from entering the U.S. Even the cruelest of enforcement policies – separating parents from their children – was largely ineffective in deterring asylum seekers from coming to the Southern border. Between April and June 2018, the federal government’s decision to implement a “zero-tolerance” policy to criminally prosecute virtually all migrants crossing the Southwest border between ports of entry without authorization led to the separation of about 2,650 children[32] from their parents. Yet, CBP figures show that the number of people traveling in family units apprehended at the Southwest border remained virtually unchanged while the policy was in place, declining slightly from 9,649 in April 2018 to 9,258 in July 2018 (a decrease of only 4.2 percent),[33] with hot summer weather potentially playing a more significant role in driving this modest reduction. The modest decline in apprehensions and increase in share of those traveling in family units suggests that the federal government’s “zero-tolerance” policy only had a limited effect in deterring families from coming to the U.S. [34]

The data above suggests that the threat of separating parents and children is unlikely to deter a parent whose children’s lives are at risk. Families facing threats of violence or murder from gangs, drug cartels, and transnational criminal organizations may do whatever it takes to flee to safety.

We Face a Humanitarian Challenge at the Border

The current situation at the Southern border represents a humanitarian challenge, not a security crisis. The number of migrants crossing the U.S.-Mexico border today remains well below the all-time high levels of the early 2000s, when more than one million individuals were apprehended crossing into the U.S. every year. In addition, the Southern border has more resources than ever today, with record-high funding from Congress provided to construct fencing, deploy technology, and situate Border Patrol agents at the border. While there has been an increase in the number of migrants coming to the U.S. compared to last year – primarily families and children fleeing violence and poverty – these individuals are primarily coming to request asylum and pose little risk to the surrounding community. The Trump administration’s focus on enforcement and deterrence belies the fact that many of these migrants are escaping harm and persecution at home by seeking protection in the U.S. Once these individuals cross the Southern border, they almost immediately turn themselves in to Border Patrol agents to start the process to request asylum.

The humanitarian challenge at the Southern border is exacerbated by the administration’s decision to impede the flow of asylum seekers who can request protection at ports of entry. The practice of “metering” increasingly backlogs the flow of asylum seekers at ports of entry by limiting the number of asylum seekers allowed to enter the U.S. each day and ordering all others to wait. The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) in the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) found in a 2018 report that the backlog created by metering “likely resulted in additional illegal border crossings.”[35]

The current situation at the Southern border cannot be resolved merely by increasing enforcement, preventing asylum seekers from entering the U.S. through ports of entry, or altering U.S. laws to make it more difficult for migrants, most of them women and children, to receive asylum. Policies aimed at deterring these families are bound to fail, given the immense danger these families face by remaining in their home countries. Congress must choose policies that correctly identify the situation at the border as a humanitarian challenge and stay true to our principles as a nation with a commitment to protect those fleeing political, social, and economic persecution.

There Are Practical Solutions

The following is a set of policy recommendations including solutions that can be implemented in the short term to better manage and process the increase in Central American migrants at our Southern border, as well as longer-term solutions that address the reasons Central Americans are leaving their home countries in large numbers.

To be successful, these solutions will require a deliberate, predictable, and consistent approach that is communicated well, and the longer-term solutions will also require a sustained commitment over a number of years.

Short-Term Solutions to Manage and Process Central American Migrants

- Use resources effectively and increase resources as necessary to better manage the flow of migrants.

- Supplement personnel and resources to expand capacity at ports of entry to handle intake and process asylum claims. Migrants who are not permitted to enter (or must wait weeks or months) at ports of entry because of capacity issues are incentivized to try to cross the border between ports of entry.

- Ensure that agencies integral to the processing of certain migrants, such as Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), have additional authority, capacity, and resources to process migrants on a similar schedule as Customs and Border Protection (CBP). While CBP must operate around the clock, other federal agencies do not have a similar mandate, which could lead to delays in processing migrants.

- Increase immigration judge teams and the number of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officers to increase capacity to handle asylum claims and work to adjudicate these claims in a timely manner. Improve resourcing of the immigration courts and asylum systems.

- Permit USCIS asylum officers to see cases through to the end. Because of their expertise and familiarity with a case, they would be able to adjudicate claims more efficiently.

- Create a border court division of the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) to hear cases rejected by the asylum officers.

- Hire child welfare experts and additional translators and medical professionals to assist with the processing of migrants at the border at new centers or in short-term detention facilities so migrants can receive accurate information about immigration laws and access translation, medical, and legal services.

- Fund upgraded or additional barriers only in areas where needed — not where sufficient barriers exist or where technology and personnel already can adequately police the border in the absence of a barrier — to ensure adequate resources for processing migrants.

- Maximize use of alternatives to detention (ATDs); detain security threats.

- To ensure adequate detention capacity for security threats, keep families and children together and release them as quickly as possible on alternatives to detention (ATDs). Provide additional resources for existing Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and ORR facilities to ensure that detainees are held in humane and adequate conditions for families and children. Detention of children should remain short term and in compliance with court orders.

- Prioritize the use of ATDs, such as case management and electronic monitoring, as a cost-effective substitute to detaining large numbers of families who pose little or no security threat. (If there are not enough electronic monitoring ATD slots, low-priority migrants should instead be placed on other types of ATDs or released on their own recognizance, particularly if they are represented by an attorney.) An American Immigration Council study published in August 2018 and examining 15 years of data found that “96 percent of asylum applicants had attended all their immigration court hearings.”[36]

- Ensure an orderly release of migrants who are not safety threats.

- Provide notice to organizations providing humanitarian assistance and release migrants in manageable numbers over a number of days so that these organizations and transportation systems are not overwhelmed.

- Ensure migrants have access to medical services while in custody so they are healthy when released.

- Provide emergency resources and humanitarian assistance to nonprofits that provide services and support to families at the border.

- Inform migrants about U.S. asylum and immigration laws.

- Conduct a public information campaign aimed at migrants in Mexico and the Northern Triangle. This campaign should work to dispel misinformation from smugglers and help migrants understand who may be eligible for asylum so they do not make the dangerous trip to the U.S. if they do not have a valid claim.

- Re-establish in-country processing (potentially working with UNHCR, the U.N. Refugee Agency) to permit those in danger the option to apply for asylum in-country. Establish other legal migration options that would permit potential asylum seekers to apply for relief before reaching the U.S.-Mexico border.

- Partner with Mexico and Northern Triangle countries to counter human smuggling operations and increase intelligence cooperation.

Longer-Term Solutions to Address the Increase of Central Americans Fleeing to the Southern Border.

- Pass immigration reform to bring our immigration system into the 21st

- Broad-based bipartisan immigration reform can expand pathways for those who want to enter the U.S. legally to find work or reunite with family while increasing border security. Congress could immediately establish temporary worker visas for Central Americans as an interim step to broader immigration reform. Immigration reform also should provide temporary protected status holders from Central American countries the opportunity to earn citizenship.

- Address the factors that lead Central Americans to leave their home countries.

- Providing foreign aid is a critical component to addressing what is causing people to leave. While the Trump administration has announced that it will withhold the remaining foreign aid allocated for the Northern Triangle countries,[37] foreign aid to our neighboring countries already has had some successes making the countries more habitable.

- Provide El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras with U.S. advisors who can assist the countries’ judicial and law enforcement institutions with the implementation of reforms that will strengthen those institutions, put an end to trafficked firearms, increase the rule of law, establish public trust in these institutions, and improve security overall.

- Enact the Central America Reform and Enforcement Act (S. 3540)[38], or a similar bill that addresses the violence and humanitarian crisis in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras by funding programs to combat corruption and criminal violence. Specifically, such legislation would direct the secretaries of state and homeland security to work together to fund programs that would help the three Northern Triangle countries work together to address gang and drug violence; track and arrest human smugglers; and address international organized crime because it may need a transnational response. This funding would be provided to nongovernmental organizations to work with the countries’ governments to establish and implement the proposed programs. Funded programs should include the community-based crime prevention programs the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) carries out under the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI)[39], which has been effective in reducing violence and strengthening civil society.

- Establish educational and agricultural programs in the Northern Triangle to improve education levels and economic conditions. Programs should teach practices to adapt to the hotter and drier conditions that have led to significant drops in crop yields, and should include vocational education specializing in fishing, forestry, and market gardening. These programs would be consistent with and support the development and poverty-reduction programs of the S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America.[40] They would aim to increase human capital overall; stimulate business investment and competitiveness in the region; and strengthen the countries’ institutions responsible for budgeting and revenue collection. The U.S. and the respective countries in the Northern Triangle would fund these programs jointly. For the U.S., the programs would be under USAID oversight.

- Increase U.S. funding to the N. World Food Program (WFP)[41] directed to assisting with their efforts in the Northern Triangle countries to address food insecurity, assist farmers, and enhance the countries’ emergency response and disaster risk mitigation. Many migrants from the Northern Triangle countries are coming from rural areas where food shortages and lack of economic opportunities are prevalent.[42]

- The United Nations General Assembly and UNHCR should address the challenges the Northern Triangle countries face by:

- Working with each of the Northern Triangle countries to establish in-country relocation areas/safe zones for those who are internally displaced. These zones would allow those fleeing persecution to stay in their home countries and at the same time protect them from the violence that forces them to leave home.

- Advocating with the Northern Triangle countries to all adopt and implement the U.N’s “Comprehensive Regional Framework for Protection and Solutions” (MIRPS,[43] its Spanish acronym).[44] This framework helps countries develop a national plan that also recognizes the regional impacts of migration and provides opportunities for countries to learn from each other.

- Engaging the Northern Triangle countries in signing and ratifying the “Arms Trade Treaty”[45] the U.N. General Assembly adopted April 2, 2013, to better regulate the small arms flow into the countries.

- Help Mexico improve its refugee and asylum systems.

- The secretaries of state and homeland security should work together to provide international aid to Mexico’s law enforcement agencies in an effort to address gang and drug violence and to investigate and curtail the activities of local cartels that participate in smuggling drugs and people from Mexico into the U.S. Such an effort would make Mexico a more acceptable place to apply for asylum.

- Assist the Mexican government with the development of a more effective asylum system so that it can take in more asylees as the country addresses its safety concerns. Improvements would include increasing the number of asylum offices around the country, streamlining entry, addressing backlogs, establishing an appeals process, and creating special visas and temporary authorization for migrants from the Northern Triangle to stay in Mexico.

- Assist the Mexican government with the creation of a public/private refugee program such as the one in the U.S. by establishing a “twinning” arrangement between the U.S. and Mexico. This arrangement would require countries to share information about design and execution of refugee programs. Mexican government officials and potential private partner organizations should be able to visit the U.S. resettlement agencies, affiliate offices, and other relevant institutions to observe and learn about the U.S. resettlement program.

- Help the Mexican government establish shelters for unaccompanied children (UACs).

- Work with Mexico to establish immigrant worker programs.

- Encourage the Mexican government to develop immigrant worker programs to make the flow of immigrant workers into Southern Mexico safer and more beneficial to both Mexico and the Northern Triangle.

- Assist with the development of these programs by offering technical assistance related to developing effective regulations and aid in making strategic industrial and infrastructure investments. Such programs would draw economic migrants and deter migrants from making the much costlier and riskier trip to the U.S. while simultaneously benefitting the Mexican economy.

- Increase U.S. refugee admissions from Northern Triangle countries.

- Assemble and deploy refugee rapid response teams to the Northern Triangle and Mexico to evaluate refugee claims and operate as a mobile Resettlement Support Center to expedite consideration of refugee claims for U.S. resettlement. The State Department would undertake this deployment through the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration.

- Increase U.S. refugee admissions, and in the annual “Presidential Determination,” increase the number of refugees allocated to the “Latin American and the Caribbean” region, which includes the Northern Triangle.

- Expand the Protection Transfer Agreement (PTA) program and encourage other countries to enter into similar agreements.

- Work with Costa Rica to explore expanding the capacity of the current PTA. The PTA allows the State Department to pre-screen Northern Triangle migrants in their home countries and transfer the most vulnerable individuals to Costa Rica, where they wait until their refugee claim is processed. The State Department should increase resources to ensure the maximum number of individuals are referred to Costa Rica, currently 200 migrants every six months.

- Develop additional PTA programs with other countries in the western hemisphere.

Conclusion

Migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras are likely to continue to arrive at the U.S. border until socioeconomic and security issues in their home countries are adequately addressed. Their decision to leave their homes and begin new lives in the U.S. is rooted in real fears about their futures that push them northward. Rather than focusing on a deterrence-based approach at the Southern border, the solution to the increasing flows of migrants from NTCs must center on effective short- as well as long-term actions based on cooperation between U.S., Mexican and the NTC governments. These solutions must also be aimed at addressing the root causes of migration. To be successful, the solutions will require a deliberate, predictable, and consistent approach that is communicated well, and the longer-term solutions will require a sustained commitment over a number of years.

References:

[1] Anderson, S. (2019, March 7). What The Latest Border Statistics Really Mean. Forbes. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/stuartanderson/2019/03/07/what-the-latest-border-statistics-really-mean/#113591a37f67

[2] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Migration FY 2019. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration

[3] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Migration FY 2019. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration ; U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions ; U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles

[4] Labrador, R. C., & Renwick, D. (2018, June 26). Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Council on Foreign Relations website: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle

[5] Dalby, C., & Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved June 7, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup/

[6] El Salvador gang violence pushes murder rate to postwar record. (2015, September 2). The Guardian. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/el-salvador-gang-violence-murder-rate-record

[7] Gagne, D. (n.d.). InSight Crime’s 2015 Latin America Homicide Round-up. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-homicide-round-up-2015-latin-america-caribbean/

[8] Dalby, C., & Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved June 7, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup/

[9] Federal Bureau of Investigation. Murder. (2018, September 10). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/murder

[10] Dalby, C., & Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved June 7, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup/

[11] Dalby, C., & Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved June 7, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup/

[12] Federal Bureau of Investigation. Murder. (2018, September 10). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/murder

[13] Dalby, C., & Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved June 7, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup/

[14] McDonald, M. (2012, May 14). Caging in Central America. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from PRI.org website: https://www.pri.org/stories/2012-05-14/caging-central-america

[15] Doctors Without Borders. Forced To Flee Central America’s Northern Ftiangle: A NEGLECTED HUMANITARIAN CRISIS. (2017, May). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Doctors Without Borders website: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/msf_forced-to-flee-central-americas-northern-triangle.pdf

[16] Congressional Research Service. Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. (2019, January 29). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf

[17] McDonald, M. (2012, May 14). Caging in Central America. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from PRI.org website: https://www.pri.org/stories/2012-05-14/caging-central-america

[18] The World Bank. The World Bank In Honduras. (2019, April 4). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from The World Bank website: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/honduras/overview

[19] The World Bank. The World Bank In Guatemala. (2019, April 4). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from The World Bank website: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/guatemala/overview

[20] Central Intelligence Agency. Central America: Guatemala. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Central Intelligence Agency website: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_gt.html

[21] The World Bank. The World Bank In El Salvador. (2019, April 4). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from The World Bank website: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/elsalvador/overview

[22] Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft/Ruhr University Bochum – Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV). WorldRiskReport 2018. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft/Ruhr University Bochum – Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV) website: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/world-risk-report-2018-focus-child-protection-and-childrens-rights

[23] Congressional Research Service. Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. (2019, January 29). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf

[24] Seay-Fleming, C. (2018, April 12). Beyond Violence: Drought and Migration in Central America’s Northern Triangle. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from New Security Beat website: https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2018/04/violence-drought-migration-central-americas-northern-triangle/

[25] Seay-Fleming, C. (2018, April 12). Beyond Violence: Drought and Migration in Central America’s Northern Triangle. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from New Security Beat website: https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2018/04/violence-drought-migration-central-americas-northern-triangle/

[26] Seay-Fleming, C. (2018, April 12). Beyond Violence: Drought and Migration in Central America’s Northern Triangle. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from New Security Beat website: https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2018/04/violence-drought-migration-central-americas-northern-triangle/

[27] Congressional Research Service. Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. (2019, January 29). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf

[28] Migration Policy Institute. President Signs DHS Appropriations and Secure Fence Act, New Detainee Bill Has Repercussions for Noncitizens. (2006, November 1). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Migration Policy Institute website: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/president-signs-dhs-appropriations-and-secure-fence-act-new-detainee-bill-has-repercussions

[29] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Mileage of Pedestrian and Vehicle Fencing by State. (2017, September 21). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/document/stats/us-border-patrol-mileage-pedestrian-and-vehicle-fencing-state

[30] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. U.S. Border Patrol Fiscal Year Staffing Statistics (FY 1992 – FY 2018). (2019, March 8). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/document/stats/us-border-patrol-fiscal-year-staffing-statistics-fy-1992-fy-2018

[31] National Immigration Forum. Enacted Border Patrol Program Budget by Fiscal Year. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://forumtogether.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BP-Budget-History-1990-2017.pdf

[32] Barajas, J. (2018, August 17). 24 migrant children under age 5 remain separated from their parents, new court filing says. PBS. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/24-migrant-children-under-age-5-remain-separated-from-their-parents-new-court-filing-says

[33] U.S. Customs and Border Protection. Southwest Border Migration FY2018. (2018, November 9). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration/fy-2018

[34] Miroff, N. (2018, August 8). Border arrest data suggests Trump’s push to split migrant families had little deterrent effect. The Washington Post. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/border-arrest-data-suggest-trumps-push-to-split-migrant-families-had-little-deterrent-effect/2018/08/08/0f452f0e-9a85-11e8-b55e-5002300ef004_story.html?utm_term=.cf7de8fc7301

[35] Office Of Inspector General. Special Review – Initial Observations Regarding Family Separation Issues Under the Zero Tolerance Policy. (2018, September 27). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Office Of Inspector General website: https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2018-10/OIG-18-84-Sep18.pdf

[36] Eagly, I., Shafer, S., & Whalley, J. (2018, August 16). Detaining Families: A Study of Asylum Adjudication in Family Detention. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from American Immigration Council website: https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/research/detaining-families-a-study-of-asylum-adjudication-in-family-detention

[37] Aleman, M. (2019, April 2). US Aid Cuts Will Spur Central America Migration, Experts Say. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.foxnews.com/world/us-aid-cuts-will-spur-central-america-migration-experts-say

[38] Congress.gov. S.3540 – Central America Reform and Enforcement Act. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/3540/text?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22central+america%22%5D%7D&r=3

[39] U.S. Department of State. Central America Regional Security Initiative. (2017, January 20). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/fs/2017/260869.htm#

[40] Congressional Research Service. U.S. Strategy for Engagement in Central America: An Overview. (2019, January 3). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Congressional Research Service website: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF10371.pdf

[41] World Food Programme. Homepage | World Food Programme. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://www1.wfp.org/

[42] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Atlas of Migration: The majority of migrants from Central America come from rural areas. (2018, December 12). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations website: http://www.fao.org/americas/noticias/ver/en/c/1174658/

[43] United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The MIRPS: A regional CRRF application. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees website: https://www.acnur.org/5b50f49c4.pdf

[44] Organization of American States. Comprehensive Regional Protection and Solutions Framework. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from Organization of American States website: http://www.oas.org/en/sare/documents/honduras_regional_conference_draft_10_aug.pdf

[45] United Nations. Arms Trade Treaty. (n.d.). Retrieved May 7, 2019, from https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=XXVI-8&chapter=26&clang=_en