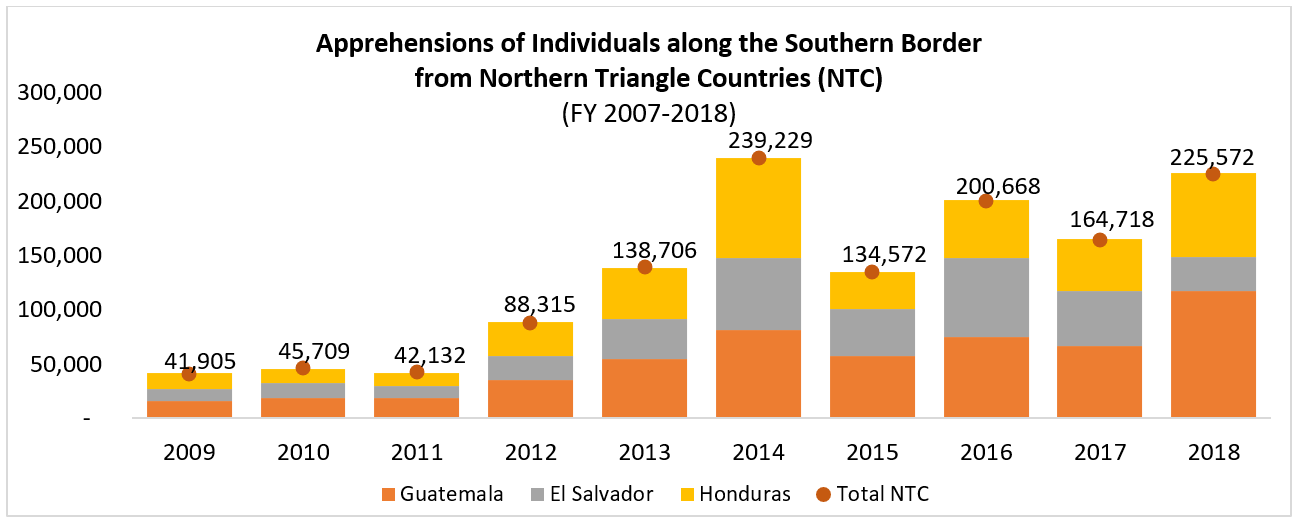

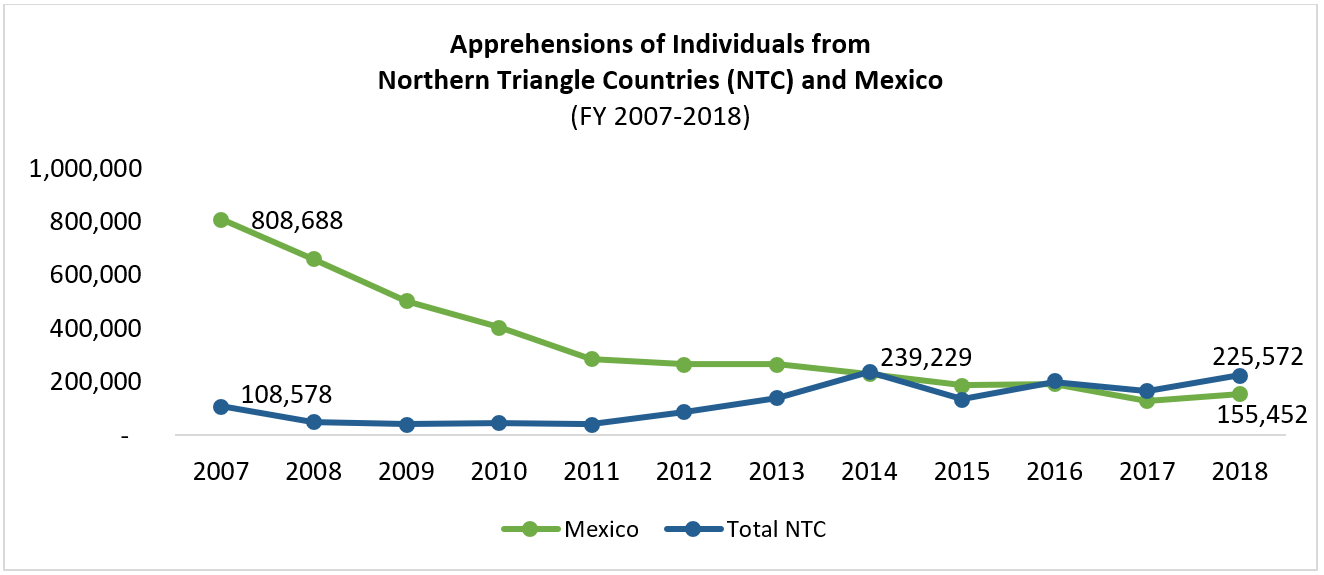

For centuries, the United States has been a popular destination for migrants from around the world. Every day, asylum seekers and other migrants are coming to the U.S. southern border. This pattern is not new. However, the demographic composition of people attempting to cross the border has changed considerably over the past decade. In 2007, the vast majority of migrants attempting to enter the U.S. through its southern border were from Mexico. In 2018, most migrants were from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala — often referred to collectively as the “Northern Triangle countries” because they are the three northernmost Central American countries. Most of the Northern Triangle migrants have been unaccompanied children and families rather than individual adults, and an increasing number of families and unaccompanied children also present themselves at one of the U.S. ports of entry to apply for asylum rather than attempt unauthorized border crossings.

Migrants from Central America leave their home countries and undergo the often dangerous journey to the U.S. for varying reasons, and comprehensive data about these reasons is unavailable. Understanding the motives that lead migrants to the U.S. is crucial to reaching well-focused immigration and foreign policy solutions to the increasing migrant flows from Central America.

Unfortunately, the debate about whether migrants come primarily because of the “pull” factors to the U.S. or because of the “push” factors motivating them to leave their countries of origin is unresolved. Past research has suggested that some come primarily for the social and economic benefits of living in the U.S., but more recent findings suggest that more decide to begin new lives in the U.S. primarily because of real fears about their futures — fears that “push” them northward despite increased border security and stricter U.S. immigration policies.

Defining ‘Push’ and ‘Pull’ Factors

Individuals around the globe migrate for a broad variety of reasons, which can be conceptualized in two general terms: “push” and “pull” factors. “Push” factors are conditions in migrants’ home countries that make it difficult or even impossible to live there, while “pull” factors are circumstances in the destination country that make it a more attractive place to live than their home countries.[1] Common “push” factors include violence, gender inequality, political corruption, environmental degradation and climate change, as well as lack of access to adequate health care and education. Common “pull” factors include more economic and work opportunities, the possibility of being reunited with family members, and a better quality of life, including access to adequate education and health care.[2]

Although the general “push” and “pull” factors describe motivational trends and patterns, they do not account for the specific and personal reasons for migrating that are unique to every individual.

Central American Migrants Coming to the U.S.

The data regarding migration from Central America does not explain whether people are coming because of push or pull factors, but the recent increases suggest new motivations for migration. While the number of migrants trying to cross the southern border between ports of entry annually has remained relatively stable during the past 10 years at around 400,000 per year,[3] the demographic makeup of those migrants has changed considerably, with Northern Triangle migrants accounting for a considerable share of the total since 2014.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector in FY2007-FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector in FY2007-FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf.

Until recently, the largest number of migrants entering the country between ports of entry (POEs) were from Mexico. However, this trend began to change in 2014, and since 2016 the number of migrants from the Northern Triangle actually has exceeded the number of Mexican migrants.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector in FY2007-FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector in FY2007-FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf.

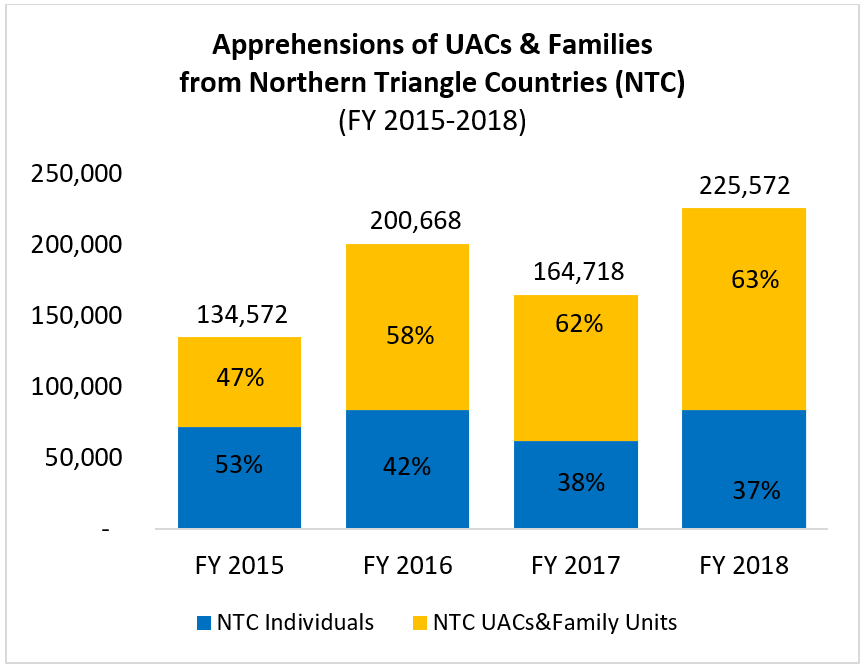

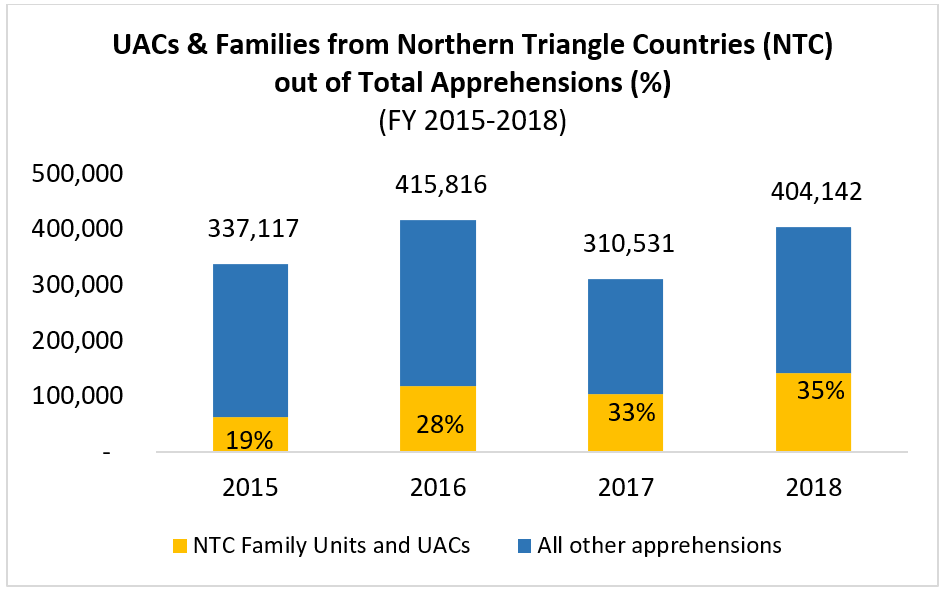

Moreover, an increasing number of Northern Triangle migrants apprehended along the southern border from FY 2015 through FY 2018 have been children and families. Between fiscal years (FY) 2015 and 2018, the proportion of family units and unaccompanied children (UACs) apprehended at the southern border increased substantially, accounting for 63 percent of all apprehensions of Northern Triangle migrants in FY 2018.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. ; Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children Statistics FY 2016. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-alien-children-statistics-fy-2016.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. ; Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children Statistics FY 2016. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-alien-children-statistics-fy-2016.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. ; Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children Statistics FY 2016. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-alien-children-statistics-fy-2016.

Source: U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions. ; Southwest Border Unaccompanied Alien Children Statistics FY 2016. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/southwest-border-unaccompanied-alien-children-statistics-fy-2016.

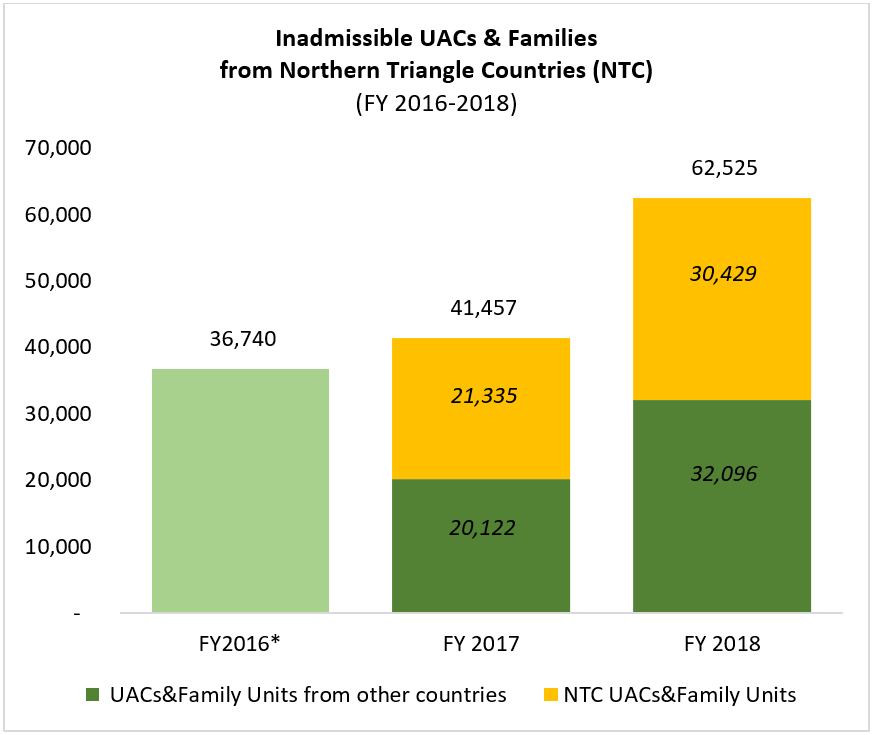

Since FY 2017, an increasing number of families and UACs from Northern Triangle countries have been presenting themselves at one of the ports of entry to seek asylum. In FY 2017 and FY 2018, children and families from the Northern Triangle accounted for about half of all UACs and family units that presented themselves to Border Patrol officers along the southern border.

*By-country breakdown data for 2016 is not available

*By-country breakdown data for 2016 is not available

Source: Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles.; Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2017. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles-fy2017.

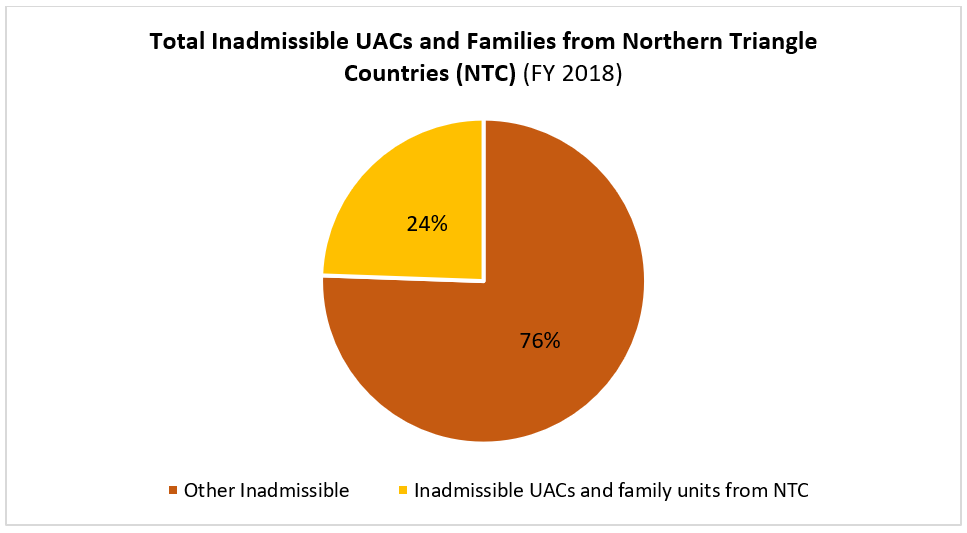

In FY 2018, UACs and families from the Northern Triangle accounted for about a quarter of all inadmissible individuals who arrived at one of the POEs along the southern border.

Source: Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles.; Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2017. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles-fy2017.

Source: Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles.; Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2017. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles-fy2017.

In 2019, more families and UACs from the Northern Triangle countries have been continuing to arrive at the U.S. southern border. As of March 2019, 74 percent of all migrants apprehended at the border were from one of the Northern Triangle countries and 58 percent were families or UACs from one of the Northern Triangle countries. [4] [5] [6]

What ‘Pushes’ Central American Migrants?

To understand the changes in these migration patterns, we need to examine the circumstances and events in the Northern Triangle countries. These countries share political, social and economic similarities, including high crime rates, pervasive gang violence, extreme poverty and corruption,[7] which all play a crucial role in migrants’ decision to leave. In the 1980s and 1990s, migration researchers concluded that economic factors were “pulling” migrants to what they perceived as a thriving U.S. economy.[8] However, current analyses of migration across the southern border attribute migration to a complex interaction between various “push” and “pull” factors motivating migrants to leave their homes.[9] Experts generally agree that the recent increase in UACs and families migrating from the Northern Triangle is attributable to immediate threats of violence, corruption and environmental degradation in these countries, which are classified as “push” factors,[10] together with contributing factors of U.S. immigration policy and practice[11] and smuggling organizations’ activities and propaganda.[12]

All three Northern Triangle countries rank among the most violent countries in the world, with significantly higher murder rates than neighboring Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama.[13] In 2015, El Salvador became the most violent not-at-war country in the world,[14] as its gang-related violence pushed the country’s murder rate to 103 per 100,000 people.[15] While the rate has since fallen considerably,[16] it still remains nearly 10 times higher than that of the United States.[17] In 2018, there were 3,340 murders in El Salvador and the country’s homicide rate stood at 51 per 100,000, down from the 81.2 per 100,000 recorded in 2016. Honduras saw 3,310 homicides in 2018 and a murder rate of 40 per 100,000 people.[18] Guatemala’s murder rate fell to 22.4 per 100,000 with 3,881 homicides in 2018.[19] In comparison, the most recent data shows that United States recorded 5.3 homicides per 100,000 people in 2017.[20]

| Homicide Rates in Northern Triangle Countries (2018) vs. United States (2017) | |

| Country | Homicide Rate |

| (per 100,000 people) | |

| El Salvador | 51.0 |

| Honduras | 40.0 |

| Guatemala | 22.4 |

| United States | 5.3 |

Gang activity is one of the main factors consistently driving the homicide rates in the Northern Triangle countries.[21] Together with a lack of governmental intervention, gang activity creates a self-perpetuating cycle of lawlessness and violence. Organized crime groups target small businesses and poor neighborhoods, recruiting members to impose and collect payments for “protection,” threatening and harming individuals who do not comply with their demands. The imminent and omnipresent nature of oppressive gang activity forces innocent people to live under the constant threat of violence. A study conducted by Doctors Without Borders revealed that among nearly 500 Northern Triangle migrants surveyed, almost 40 percent mentioned direct attacks or threats to themselves or their families, extortion or gang-forced recruitment as the main reason for fleeing their countries, and 43.5 percent reported they had a relative who died due to violence in the previous two years.[22] Additionally, a recent Congressional Research Services (CRS) study showed that Salvadoran and Honduran victims of crimes are 10 to 15 percent more likely to migrate than those who have not had such an experience.[23]

Moreover, large numbers of people in the Northern Triangle countries live in poverty (defined by the World Bank as living at $1.90 or less per person per day[24]), which makes them more likely to be victimized by gangs that use their socioeconomic vulnerability to manipulate them and target them for membership recruitment and extortion.[25] More than 66 percent of Hondurans lived in poverty in 2016.[26] Moreover, Guatemala has faced some of the worst poverty levels (around 60 percent) in Latin America.[27] El Salvador’s poverty rate hit 31 percent in 2016.[28] Gangs profit off rising poverty levels by ramping up recruitment efforts in poor communities to increase their hegemony over the government and society. The vicious cycle is spurred even more by corrupt governments and their inability and unwillingness to help their most vulnerable citizens.

In addition to violence and corruption, climate change-induced environmental threats also “push” Northern Triangle migrants to leave their home countries. The World Risk Index, a measure of disaster risk applied to 172 countries worldwide, revealed that Guatemala and El Salvador are among the 15 countries particularly prone to natural disasters, such as earthquakes and droughts. Because about 25 percent of the countries’ workforce is employed in the agriculture sector,[29] changing climate and natural disasters have a heavy impact on the population’s well-being. In 2015, a massive drought plagued the Northern Triangle, leading to financial disaster for farmers and resulting in a food shortage whose impact was most devastating on impoverished communities.[30] Individuals who were already fearful of gang violence became even more motivated to leave their countries because the drought caused food insecurity. In the most heavily impacted areas, migrants cited “no food” as the main reason for leaving their country.[31] Guatemala has one of the highest food insecurity and malnutrition rates in Latin America, with nearly 1 million Guatemalans suffering from moderate to severe food insecurity.[32] In 2018, Guatemala and Honduras had the second- and third-highest hunger levels in Central America and the Caribbean in the International Food Policy Research Institute’s Global Hunger Index,[33] a measure that tracks hunger at global, regional and national levels; Haiti ranked first.

Are Central American Migrants Being ‘Pulled’ to the U.S.?

The conditions in the Northern Triangle countries explain why people desire to migrate to the U.S., but there’s no denying that the conditions in the U.S. may be a contributing factor driving their migration. A common misperception, however, is that “pull” factors, such as socially, politically and economically attractive circumstances, explain solely why migrants come to the U.S. While the U.S. has been known as a country of unlimited possibilities with a growing economy, an excellent educational system, low levels of poverty and low levels of violence,[34] these factors alone are not the only forces “pulling” migrants to undergo the long and dangerous journey to the U.S. border to face an uncertain fate.

Family reunification is another common “pull” factor, as many Northern Triangle migrants have relatives who have already settled in the U.S. About 1 in 5 Salvadorans and 1 in 15 Guatemalans and Hondurans have migrated to the U.S., making the U.S. an attractive destination for their children and other family members fleeing the region.[35]

A comprehensive study about the causes of the increased migration at the U.S.-Mexico border published by the South Texas College of Law Houston showed that in Northern Triangle countries, the “word of mouth” phenomenon is a tangentially related factor “pulling” individuals to the U.S.[36] Smugglers (sometimes referred to as “coyotes”), who profit from bringing migrants across the southern border, encourage already vulnerable individuals to leave their homes, pushing them past a “psychological tipping point” by providing them with inaccurate information about the U.S. immigration system.[37] They orchestrate a “campaign of rumors,” exaggerating the system’s navigability and the likelihood of being granted asylum and scaring individuals into paying exorbitant amounts of money to be smuggled into the U.S.[38] A study of more than 400 interviews of migrants from the Northern Triangle revealed that most migrants do not possess any knowledge of the U.S. immigration system,[39] suggesting this “pull” factor is based on falsehoods rather than accurate perceptions about political realities and immigration laws in the U.S.

Conclusion

It is impossible to explain with absolute precision why migrants come to the U.S. because no comprehensive data tracks all of the reasons. Given the current realities in the Northern Triangle countries and recent research, it is reasonable to conclude that push factors — social, political and economic realities forcing people to leave their home countries — outweigh the pull factors in the U.S. that make it a more attractive place to live. Although more research about migrants’ reasons for leaving their home countries is needed, it seems likely that migrants from the Northern Triangle countries will continue to arrive at the U.S. border until socioeconomic and security issues in their home countries are adequately addressed.

In the past few years, the Trump administration has implemented a number of policies to discourage migrants from coming to the U.S., such as family separations; metering, in which U.S. Customs and Border Protection limits the number of people who can request asylum at a port of entry; and Migrant Protection Protocols at the border, in which some migrants are returned to Mexico for the duration of their immigration proceedings. However, a lack of knowledge about which immigration policies particularly draw immigrants to the U.S.,[40] combined with evidence that migrants are unfamiliar with the U.S. immigration system, make it unlikely that these deterrence efforts will stop individuals from migrating north.[41]

Rather than focus on U.S. domestic policies and a deterrence-based approach at the southern border, the way to address the increasing flows of migrants from the Northern Triangle must center on U.S. cooperation with Mexico and the Northern Triangle countries to address the root causes of migration.

[1] Root Causes of Immigration, Justice for Immigrants, https://justiceforimmigrants.org/what-we-are-working-on/immigration/root-causes-of-migration/ (last updated Feb. 14, 2017).

[2] Ibid.

[3] U.S. Border Patrol Nationwide Apprehensions by Citizenship and Sector in FY2007-FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2019-Mar/BP%20Apps%20by%20Sector%20and%20Citizenship%20FY07-FY18.pdf.

[4] Southwest Border Migration FY 2019. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/sw-border-migration.

[5] U.S. Border Patrol Southwest Border Apprehensions by Sector FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/usbp-sw-border-apprehensions.

[6] Southwest Border Inadmissibles by Field Office FY2018. U.S. Customs and Border Control, Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/ofo-sw-border-inadmissibles.

[7] Labrador, R. C., Renwick, D. Central America’s Violent Northern Triangle, Council on Foreign Relations, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/central-americas-violent-northern-triangle (last updated June 26, 2018).

[8] See generally Kathleen M. Johnson, Note, Coping with Illegal Immigrant Workers: Federal Employer Sanctions, 1984 U. Ill. L. Rev. 959 (1984).

[9] Chishti, M., Hipsman, F. (2016, February 18). Increased Central American Migration to the United States May Prove an Enduring Phenomenon. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/increased-central-american-migration-united-states-may-prove-enduring-phenomenon.

[10] Rempell, S. Note, Credible Fears, Unaccompanied Minors, and the Causes of the Southwestern Border Surge, 18 Chap. L. Rev. 337 (2015).

[11] Wilson, J. H. (2019, January 2019). Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf.

[12] Farah, D. Five Myths about the Border Crisis. (Aug. 8, 2014). The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/five-myths-about-the-border-crisis/2014/08/08/1ec90bea-1ce3-11e4-ab7b-696c295ddfd1_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.868b3aa9c20f.

[13] Dalby, C., Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup.

[14] El Salvador gang violence pushes murder rate to postwar record. (2015, September 2). The Guardian. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/el-salvador-gang-violence-murder-rate-record.

[15] Gagne, D. (2016, January 14). InSight Crime’s 2015 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-homicide-round-up-2015-latin-america-caribbean/.

[16] Dalby, C., Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup.

[17] Murder. (2018, September 10). Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/murder.

[18] Dalby, C., Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup.

[19] Dalby, C., Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup.

[20] Murder. (2018, September 10). Federal Bureau of Investigation. Retrieved from https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2017/crime-in-the-u.s.-2017/topic-pages/murder.

[21] Dalby, C., Carranza, C. (2019, January 22). InSight Crime’s 2018 Homicide Round-Up. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/insight-crime-2018-homicide-roundup.

[22] Forced To Flee Central America’s Northern Triangle: A Neglected Humanitarian Crisis(Rep.). (2017, May). Retrieved July 23, 2019, from Doctors Without Borders website: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/sites/default/files/2018-06/msf_forced-to-flee-central-americas-northern-triangle.pdf.

[23] Wilson, J. H. (2019, January 2019). Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf.

[24] Ferreira, F., Jolliffe, D. M., & Prydz, E. B. (2015, October 4). The international poverty line has just been raised to $1.90 a day, but global poverty is basically unchanged. How is that even possible? The World Bank. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/international-poverty-line-has-just-been-raised-190-day-global-poverty-basically-unchanged-how-even.

[25] Ramirez, E. G. Migration from Central America, European Parliament (Oct. 2018), https://www.pri.org/stories/2012-05-14/caging-central-america.

[26] The World Bank In Honduras. The World Bank. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/honduras/overview.

[27] The World Factbook: Guatemala. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/print_gt.html.

[28] The World Bank In El Salvador. The World Bank. Retrieved July 23, 2019, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/elsalvador/overview.

[29] Wilson, J. H. (2019, January 2019). Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf.

[30] Seay-Fleming, C. Beyond Violence: Drought and Migration in Central America’s Northern Triangle, News Security Beat (Apr. 12, 2018), https://www.newsecuritybeat.org/2018/04/violence-drought-migration-central-americas-northern-triangle/.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Wilson, J. H. (2019, January 2019). Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ball, I., Rosenblum, M. R. (2016, January). Trends in Unaccompanied Child and Family Migration from Central America(Rep.). Retrieved July 23, 2019, from Migration Policy Institute website: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/trends-unaccompanied-child-and-family-migration-central-america.

[36] Rempell, S. Note, Credible Fears, Unaccompanied Minors, and the Causes of the Southwestern Border Surge, 18 Chap. L. Rev. 337 (2015).

[37] Douglas Farah, Five Myths about the Border Crisis, The Washington Post (Aug. 8, 2014), https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/five-myths-about-the-border-crisis/2014/08/08/1ec90bea-1ce3-11e4-ab7b-696c295ddfd1_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.868b3aa9c20f.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Elizabeth G. Kennedy, ‘No Place for Children’: Central America’s Youth Exodus, InSight Crime (June 23, 2014), https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/children-central-america-youth-exodus-us-border/.

[40] Wilson, J. H. (2019, January 2019). Recent Migration to the United States from Central America: Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved July 22, 2019, from https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45489.pdf.

[41] Elizabeth G. Kennedy, ‘No Place for Children’: Central America’s Youth Exodus, InSight Crime (June 23, 2014), https://www.insightcrime.org/news/analysis/children-central-america-youth-exodus-us-border/.