It was not inevitable that we would arrive at this juncture. As recently as 2013, after the U.S. Senate passed comprehensive, bipartisan immigration reform legislation, the Republican-controlled U.S. House was signaling that it would take up a bill. At the southern border, moving images of thousands of unaccompanied young people fleeing violence in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras were not yet on nightly newscasts. The United Kingdom was still firmly in the European Union. The Syrian refugee crisis was yet to horrify the world.

Then history swiftly intervened.

In short order, dramatic events in faraway places reached the palm of our hand. The fragmentation of media and the increasing influence of social media helped bring these changes into sharp focus. For Americans worried their children would not be better off than they are, it felt like the movement of goods, people, commerce, and ideas had accelerated to the point that the world was at the nation’s doorsteps.

Old assumptions about what’s threatening, or what’s promising, were called into question. Images of the Syrian refugee fleeing war, the young Salvadoran family seeking a new beginning, reached Americans who were losing trust in their government. More and more Americans started to perceive that the family they saw on a boat or on a train could become a neighbor in a matter of weeks. By the time Donald Trump descended the escalator and launched an unlikely bid for the presidency in June 2015, the concept of a cohesive American identity was being questioned.

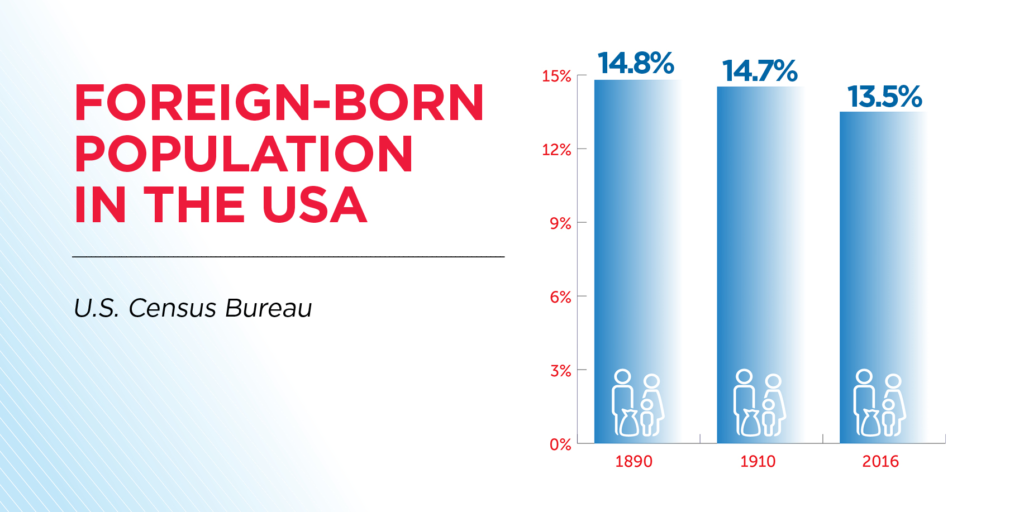

And yet in a historical context, what we’re experiencing is not new. In 1890 and again in 1910, the foreign-born made up at least 14.7 percent of the nation’s population.[1] Decades of xenophobia and political backlash followed the 1910 crest, resulting in multiple laws restricting immigration.

By 2016, the foreign-born share of the U.S. population nosed closer to these historic highs, reaching 13.5 percent. Today, as some 68.5 million people[2] are physically displaced around the world and international migration has grown to 258 million, the xenophobia and political backlash have returned. As Muzaffar Chishti, director of the Migration Policy Institute at New York University law school, told Steve Levine of Axios, “We’ve begun the 21st century as we began the 20th. The target may be different, but the anxiety is the same.”[3]

We've begun the 21st century as we began the 20th. The target may be different, but the anxiety is the same.

The changes and the anxieties are most pronounced in rural and suburban communities. Take Luzerne County, which includes and surrounds Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The county’s diversity index — which measures the variance of the racial and origin-based composition of a given population — increased by 360 percent from 2000 to 2015. It was one of the counties that saw a dramatic swing from blue to red in 2016. President Barack Obama carried Luzerne County by nearly 5 percentage points in 2012, and President Trump carried the county by more than 19 points four years later.[4]

This divide between rural, suburban and urban communities is only widening. Estimates indicate that by 2040, approximately 70 percent of Americans will live in the 15 largest states. Even as New York City, Los Angeles, and Houston continue to see population growth, the 30 percent of the country’s population — living in smaller states without major metropolitan centers — will hold disproportionate power when it comes to deciding who goes to the Senate, who wins the electoral college, and what type of immigration system we can build together.[5]

What will our democracy look like in 2040?

Will it resemble Webster City, Iowa, where a changing community in a red state bands together to save the local theater?[6] Or will it be a microcosm of Burien, Washington, where, in a blue state, the city’s first Latino mayor was attacked?[7]

To break through the tribalism — essentially, to live up to “out of many, one” — we must heed the words of the woman in our Myrtle Beach Living Room Conversation who reminded us that we must know people, and actively listen to them, if we want to form an educated opinion. Her sentiment applies to all of us, native-born Americans and immigrants alike.

Charting a viable path toward compromise and common purpose requires us to meet people where they are, understand their hopes and fears in the midst of fast-changing communities, and, ultimately, work together to hold elected officials from both parties accountable for divisive rhetoric.

Continue reading part 3: Out of Many, One

***

[1] “The Foreign-Born Population in the United States,” United States Census Bureau, accessed October 1, 2018, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/pdf/cspan_fb_slides.pdf.

[2] “Figures at a Glance,” United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, accessed September 6, 2018, http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/figures-at-a-glance.html.

[3] Steve Levine, “U.S. could face prolonged era of anti-immigrant fever,” Axios, September 20, 2018, https://www.axios.com/peak-immigration-peak-hysteria-united-states-0dc178c6-3333-4bd7-8374-34056a17a43f.html.

[4] Thomas B. Edsall, “How Immigration Foiled Hillary,” The New York Times, October 5, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/05/opinion/clinton-trump-immigration.html.

[5] Phillip Bump, “By 2040 two-thirds of Americans will be represented by 30 percent of the Senate,” The Washington Post, November 28, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/politics/wp/2017/11/28/by-2040-two-thirds-of-americans-will-be-represented-by-30-percent-of-the-senate/?utm_term=.826487ecb26c.

[6] Jeffrey Fleishman, “Immigration. Technology. Trump. A lot has changed in small-town America. One Iowa town drew the line at its movie theater,” Los Angeles Times, September 16, 2018, http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-ca-webster-city-theater-20180916-story.html.

[7] Adeel Hassan, “Police May Seek Hate-Crime Charge in Attack on Latino Mayor,” New York Times, July 24, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/24/us/jimmy-matta-attack-sanctuary-city.html.