Since 2011, the National Immigration Forum has focused our organizing, communications and advocacy resources on conservative and moderate faith, law enforcement and business leaders living in the Southeast, South Central, Midwest and Mountain West. Realizing that we needed to increase our engagement with voters themselves, in 2017 we expanded our digital footprint to engage conservative voters in key regions. This year’s “Living Room Conversations,” a learning campaign to help us understand rural and suburban communities experiencing change across demography, culture, and the local economy, was a logical and necessary next step.

For the conversations, the Forum’s organizing team recruited conservative and moderate members of the aforementioned constituencies, as well as military veterans and others. Although participants were not drawn from a random sample, the campaign’s invaluable conversations — open, honest, and authentic — in 26 rural and suburban communities, along with research, polling, and demographic data, gave us a comprehensive perspective.

To complement our findings, we partnered with More in Common, an international initiative to build stronger and more resilient communities and societies, which had just completed an exhaustive quantitative survey of the American public, as well as focus groups and interviews. That work examined the landscape of American public opinion through analysis of seven different population segments they call America’s “hidden tribes.” Forum staff were trained to facilitate conversations utilizing a discussion guide More in Common researchers designed. The guide helped us lead robust and open conversations that included themes of identity, community and polarization, and perceptions about immigrants.

The Polling

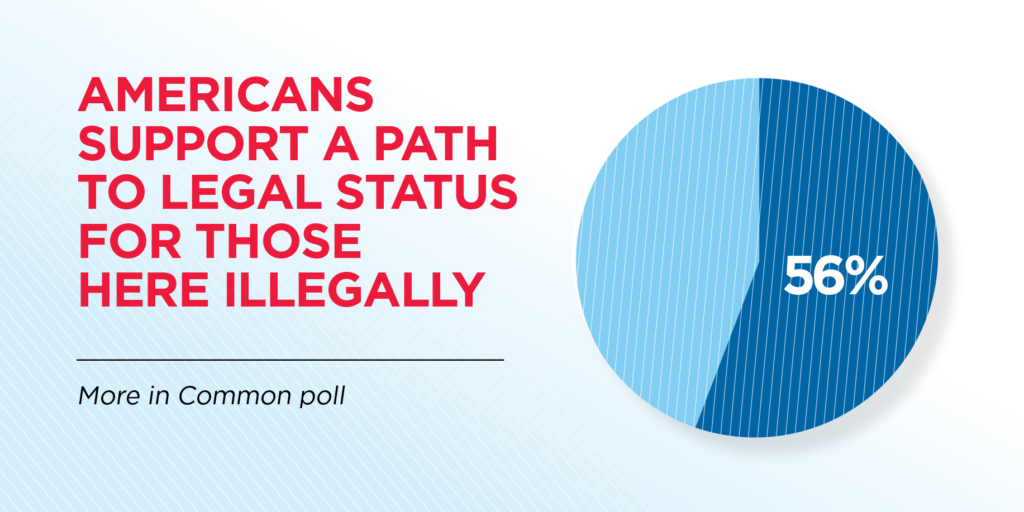

Polling data on Americans’ attitudes indicate that most Americans believe immigration is a positive for the country. According to More in Common’s poll, 56 percent of Americans believe that America’s immigrant population is good for our country.[1]

People want leaders to hear their concerns. They seek information they can trust. While many express skepticism, there is an unambiguous desire to rise above polarization and divisiveness in order to build coalitions and make overdue policy reforms. In the same poll, 60 percent said that we need to heal as a nation rather than “defeat evil” within it.[2]

Half of independents in an August 2018 Morning Consult/POLITICO survey said immigrants strengthen our country because of their hard work and talent.[3] A recent report by the Bipartisan Policy Center and Luntz Global found that although clear majorities prefer “strong enforcement both at the border and interior, 69 percent of respondents also support a path to legal status for those here illegally.”[4] Passing a Dream Act — to ensure young people who came to this country as minors can stay legally and ultimately gain citizenship — consistently polls near 80 percent approval.[5]

If the political polling suggests broad agreement on immigration policy, why does our immigration debate seem fractious?

Is it because those in the middle — the suburban, exurban, rural and independent-leading voters who will play an outsize role in determining the nation’s legislative agenda for decades to come — are split on which party they trust on immigration? Yes and no. While 35 percent of this segment trust Democrats and 34 percent trust Republicans,[6], often, Americans who belong to this part of the population hold nuanced views and can see value in both sides of the arguments. The reality is their perceptions of immigration are more complicated than polling allows us to understand.

Issues of identity...and not economics were the driving forces that determined how people voted, particularly white voters.

One example lies in a new concept known as “racialized economics” that emerged during the 2016 election season. The authors of a new book, Identity Crisis, define the term as “the belief that undeserving groups are getting ahead while your group is left behind.” As Washington Post columnist Dan Balz explained, “Issues of identity — race, religion, gender and ethnicity — and not economics were the driving forces that determined how people voted, particularly white voters.”[7]

We need to move past arguments of either-or, e.g. culture or economics. As our conversations demonstrated, Americans in these segments often do not see it as either one or the other, or in black or white terms. Framing immigration solely through the lens of economics is not likely to help. Overlooking people’s economic concerns would be an error, but so would underestimating the power of identity considerations.

Identity

We know from recent data that 69 percent of Americans — including 56 percent of Republicans — believe immigrants are “an important part of American identity.”[8] But what shined through in our conversations was that the concept of “identity” speaks as much to people’s hopes as to their fears.

In Corpus Christi, Texas, we heard about the loss of American identity, while in Memphis, Tennessee, we heard that the church can be a powerful entity that organizes efforts to build transformative and inclusive national identities. In Gainesville, Florida, a man told us that “we are tribal and can’t handle difference,” whereas up the road in Tallahassee, we heard, “One of America’s proudest and most beautiful things is that it is a melting pot of cultures.” In Bentonville, Arkansas, a participant remarked, “You’re a little bit of everything, and that’s really what America is … and that is the beauty and some of the angst in America … that you don’t want to give up your heritage.”

Numerous participants told us their identities were tied to their local communities, their neighborhoods, their sense of place.

And with change taking hold all around them, we watched law enforcement officers, small business owners, pastors — in real time — soul-searching around what these changes mean to their own identities. Those who were hopeful saw their identities tied up in larger themes of values and ideals. Those who were fearful saw “an identity crisis” around them.

Both were looking for a type of political leadership that is in short supply these days.

More in Common’s research offered valuable insight to these complexities of identity. They concluded, “To bring Americans back together, we need to focus first on those things that we share, and this starts with our identity as Americans.” Questions of race, religion, and patriotism led to competing frames.

But, “One belief that brings Americans together is a sense that the country is special.”

We observed that when Living Room Conversations participants with different religious or political beliefs felt their individual concerns were being heard, the tension in their voices dissipated, and their faces brightened. The discussions turned to a need for solutions, not divisions. In our conversations, we saw the same challenge More in Common found in their data: a need for new approaches and a different conversation on immigration that help people come together.

Three Fears

To meet this challenge, we must address head-on the fears that polarize the immigration debate. We used the Living Room Conversations to better understand three areas in which fears can influence Americans’ perceptions of immigrants and immigration:

- Culture: Are immigrants and refugees isolating or integrating? Do they live in isolated enclaves, or are they immersed in the community, learning English and becoming American?

- Security: Are immigrants and refugees threats or protectors? Are they national security or public safety threats, or do they make positive contributions to communities, even serving in law enforcement and in the military?

- Economy: Are immigrants and refugees takers or givers? Are they taking jobs and benefits, or are they economic contributors?

Culture

A participant in El Paso, Texas, captured the tension around culture: “It’s just easy to be American, and that is what this country is about, that we assimilate and unite as Americans … and I see that as a problem with some immigrants that want to isolate themselves and try to continue their own cultural behaviors — styles and behaviors … while they want to take advantage of the privileges of America … ”

Culture is difficult but important to define in the context of the immigration debate. For some, issues of race and ethnicity were central. For others, language determined whether an immigrant was integrating into American culture. Diversity and inclusion were also a consistent theme; as one participant in Fresno, California, said, “We don’t celebrate diversity … and too often it’s been us and them.”

Culture is difficult but important to define in the context of the immigration debate.

In Appleton, Wisconsin, we heard that immigration “grows our culture, makes us more educated, [and] better people.” In Lubbock, Texas, a participant remarked, “I think [immigrants] bring a lot to our community by way of service and family values.” But in Las Vegas, Nevada, we heard that although immigrants are viewed as patriotic and hardworking, there were anxieties around a loss of cultural and language unity.

The conversations echoed More in Common’s findings that freedom, equality and the American Dream were consistently identified as beliefs that make someone American. Also, among the More in Common “tribes” to the middle and right of the spectrum, the ability to speak English becomes more valued as an important factor in someone being seen as American, which is similar to what we have observed.

Security

Since the Sept. 11 attacks, security and terrorism concerns have loomed large in the nation’s immigration debate. More recently, the administration’s enforcement actions at the border and in the interior, along with progressive efforts to “Abolish ICE” and create “sanctuary cities,” have further polarized the debate. Our conversations indicated that, to a certain degree, personal relationships mitigated fears that center on security. But many participants indicated that portrayals of immigrants as security threats are pervasive throughout the media — even if these participants believe that such portrayals are misleading.

Our conversations indicated that, to a certain degree, personal relationships mitigated fears that center on security.

Some 65 percent of Americans, including 42 percent of Republicans, do not believe that undocumented immigrants are more likely to commit serious crimes, according to Pew Research.[9] In the border town of El Paso, we observed a tension between some Americans wrestling with being compassionate as they fear threats posed by unauthorized immigration. The conversation in Mesa, Arizona, which included a handful of local law enforcement officers, revealed that although issues of legality and criminality continue to plague local residents’ perceptions and attitudes, participants generally agreed that immigrants do not pose an increased security threat. In Parker, Colorado, the sense among participants was that the broader community believed immigrants pose security threats.

While we did not specifically examine participants’ perceptions of refugees, other research points to concerns that are worth highlighting. Sixty-four percent of Americans are concerned that the refugee screening process “is not tough enough to keep out possible terrorists,” but 63 percent simultaneously believe that “people should be able to take refuge in other countries, including America, to escape from war or persecution.”

Economy

As American Action Forum President Douglas Holtz-Eakin said in 2016 before the House Ways and Means Committee, from World War II to 2007, the economy grew fast enough that GDP per capita — a crude measure of the standard of living — doubled on average every 35 years, or one working career. Coming out of 2008’s Great Recession, projections indicated that it would double every 75 years. And, in 2016, those households that worked full-time for the full year saw zero increase in their real incomes. As Holtz-Eakin put it, “The American Dream is disappearing over the horizon.”[10]

In this context, it is not surprising that American parents are worried their children’s standard of living will not exceed their own. Therefore, their fear that the new immigrant family living next door is going to take from America is legitimate. This fear manifested in different ways in our conversations across the country.

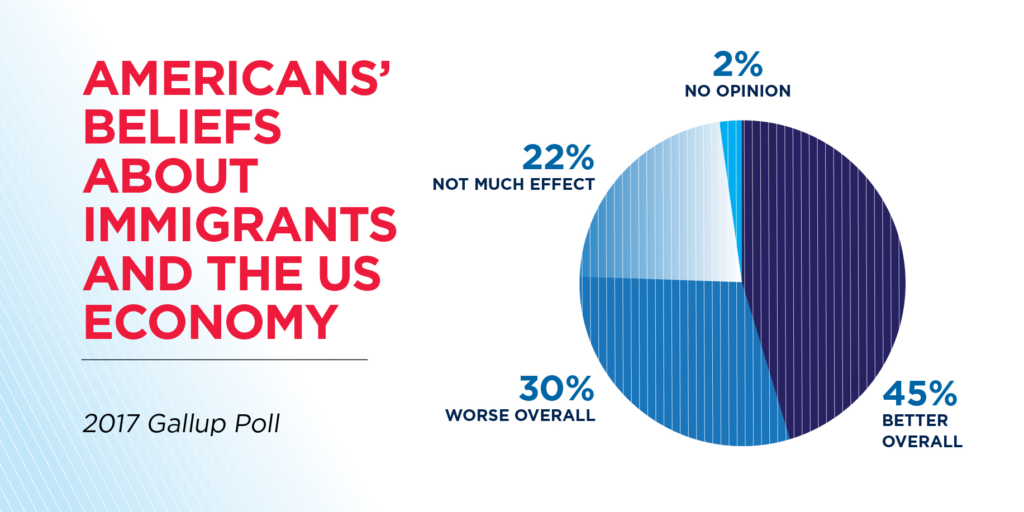

We often hear that immigrants have a bootstraps mentality — they work as hard as they can to build a better life. Data suggest that these participants are echoing national sentiment. A 2017 Gallup Poll found that 45 percent of Americans believe immigrants make the economy better overall, compared with 30 percent who believe immigrants make the economy worse overall.[11] It’s a sentiment that lines up with the contributions immigrants make to the U.S. economy: According to New American Economy, immigrants paid $105 billion in state and local taxes, and around $224 billion in federal taxes, in 2014.[12]

Participants in southern border communities, where the economy is closely tied to Mexico and to immigration, recognized the economic benefit of immigration. In San Marcos, California, participants saw that the economy is dependent on the ability of businesses to buy and sell in both the U.S. and Mexico. There was general agreement among participants in Corpus Christi that immigrants were an economic benefit. On the other hand, in Spartanburg, South Carolina, participants remarked that some in the community invoked the economy as a reason to close borders and deport people here without authorization.

Fears related to the economy can be persistent. We can address questions of culture and security only to have questions about jobs and trade linger. In the end, many Americans fear that the Mexican immigrant next door, or the Mexican in Mexico, will take their job.

Taken together, the 26 “Living Room Conversations” left us with a powerful realization: American identity is being reshaped as perceptions related to culture, security, and the economy are shifting.

Quickly changing demographics are not solely responsible; the industries of the past are giving way to the industries of the future, and the transition from a post-industrial to a knowledge-based economy is disruptive. New technologies, social norms and conventions are accentuating the way many Americans view issues such as immigration. When it comes to identity in the context of culture, security, and the economy, there is both optimism and concern.

“It’s very easy to hate from a distance,” one participant in Spartanburg said. But as people get to know the immigrant family next door, at their child’s Little League games, or one pew over at church, they come to understand them, appreciate them, love them, and value their individual contributions to the larger American story. The challenge in front of us is whether we can bridge the personal relationships with a broader perception of immigrants.

Continue reading part 4: A defining moment

***

[1] Hawkins, S., Yudkin, D., Juan-Torres, M., & Dixon, T. (2018), “Hidden tribes: A study of America’s polarized landscape.” Report prepared for More in Common.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Cameron Easley, “Independents See Immigration As Defining Partisan Issue,” Morning Consult, August 16, 2018, https://morningconsult.com/2018/08/16/independents-see-immigration-defining-partisan-issue/.

[4] “BPC Data Points to a New Middle on Immigration Reform,” Bipartisan Policy Reform, July 17, 2018, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/press-release/bpc-data-points-to-a-new-middle-on-immigration-reform/.

[5] “New Poll: Latino, AAPI, Native American, Black, and White Voters in Battleground Districts,” Latino Decisions, July 24, 2018, http://www.latinodecisions.com/blog/2018/07/24/new-poll-latino-aapi-native-american-black-and-white-voters-in-battleground-districts/.

[6] Cameron Easley, “Independents See Immigration As Defining Partisan Issue,” Morning Consult, August 16, 2018, https://morningconsult.com/2018/08/16/independents-see-immigration-defining-partisan-issue/.

[7] Dan Balz, “A fresh look back at 2016 finds America with an identity crisis,” The Washington Post, September 15, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/a-fresh-look-back-at-2016-finds-america-with-an-identity-crisis/2018/09/15/0ac62364-b8f0-11e8-94eb-3bd52dfe917b_story.html?utm_term=.50bae1a13332.

[8] NPR Press Room, “NPR/Ipsos Poll: American Views on Immigration Policy,” NPR, July 16, 2018, https://www.npr.org/about-npr/629415700/npr-ipsos-poll-american-views-on-immigration-policy.

[9] “Shifting Public Views on Legal Immigration Into the U.S,” Pew Research Center, June 28, 2018. http://www.people-press.org/2018/06/28/shifting-public-views-on-legal-immigration-into-the-u-s/#fewer-are-bothered-by-contact-with-immigrants-who-speak-little-english

[10] Douglas Holtz-Eakin, “Addressing the Growth Challenge,” United States House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, February 2, 2016, accessed October 1, 2018, https://waysandmeans.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/20160202FC-Holtz-Eakin-Testimony-CLEAN.pdf.

[11] “Immigration,” Gallup, accessed September 6, 2018, https://news.gallup.com/poll/1660/immigration.aspx.

[12] “Taxes and Spending Power,” New American Economy, accessed October 2, 2018, https://www.newamericaneconomy.org/issues/taxes-spending-power.