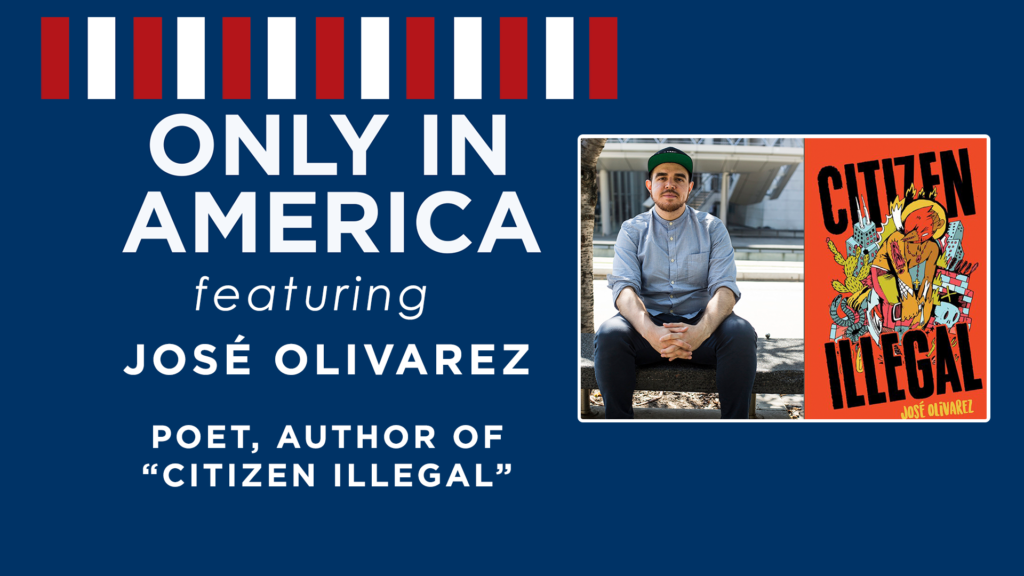

José Olivarez is a poet, educator and performer. He co-hosts the podcast “The Poetry Gods” and his debut collection, “Citizen Illegal,” received widespread critical acclaim and was a finalist in the 2019 PEN America Literary Awards. Born in Chicago to Mexican immigrant parents, José was raised with his three younger brothers in Calumet City, Illinois.

In this week’s episode, José recites some of his poems and talks to Ali about their meaning, how he uses them to communicate with his parents, and his mother’s solution for all ailments.

More Only in America Episodes Like what you hear? Click below to find all episodes of "Only in America"

Transcript

José: [00:00:00] So my name is José Olivares. I am a poet. I’m an educator. I’m a performer. I was born in the city of Chicago, raised in Calumet City Illinois, which is a suburb of Chicago. And I live in New York City currently.

Ali: [00:00:14] How did your family get to Chicago and you met?

[00:00:16] My dad and my mom are both from Canadas de Obregon, which is a small village in Jalisco, Mexico, and my dad was back and forth between the United States and Mexico for a number of years doing a bunch of different jobs. He was a migrant farm worker at times. He worked at a circus for a little bit and then he got word that there were permanent jobs in Chicago in the steel mills. So that’s when he went back to Mexico married my mom and then together they crossed the border in the trunk of a car and made their way to the city of Chicago where me and my brothers were born.

Ali: [00:00:55] Did they share with you that experience?

José: [00:00:57] They’ve shared with me bits and pieces. They’d rather not talk about it. Whenever we asked you know they want to know why we’re asking about that stuff. They would kind of rather leave that part behind them and concentrate on. Where we’re at now and what we’re up to now.

Ali: [00:01:14] Yeah I find the same thing with my parents. They’ll talk about it but it takes a while and you have to kind of chip away in like the same thing. My grandfather was towards the end of it. His time before he really started talking about it.

José: [00:01:26] Yeah. And so with my parents I think that’s something that I try each time that I talk to them to get a little bit more of the story and talk to them more and more because I don’t know I feel like in moving to the United States, There was like almost an erasure of this part of their lives and for me, I’m really interested in knowing who my parents were when they met each other who they were when they decided to make this journey right. That’s like a big decision, I imagine.

Ali: [00:01:56] So what led you to poetry?

José: [00:01:57] That’s a good question. When I was a teenager poetry was the last thing on my mind for a long time. Ultimately what led me to poetry was just that poetry was the art form where I was given permission to tell my own story and to investigate my own life. So I was always reading a ton of books but. It seemed like the majority of the writers that we were studying were white and either from nobility or they had passed away a long time ago I just had no idea that people were allowed to tell their own stories until I saw poetry for the first time. Until I had the experience of like watching teenagers perform poems about their lives and for me that’s when they click. I can also write about my family and I can write about my neighborhood and maybe people will listen.

Ali: [00:02:44] Is poetry a way for you to tell your parents story?

José: [00:02:48] For me, I can’t tell their story in part because all of the silences that exist, right? I think that there is a lot that I want to say to my parents and a lot that I want to know from them, a lot that I want them to say to me, but because there’s [00:03:04] like [0.2] this distance in our relationship which is not to say that we’re not tight but there’s unsayable things between us and so poetry is a way to try and say those things. For me to attempt to make that reach out to them and too also imagine what they might say back to me you know hopefully we get to a place in our relationship where we can be totally free and open with one another but if not I can still, kind of reach for that in the poems and hope that also then makes open our relationship more.

Ali: [00:03:34] One of the poems that you wrote was “My Mom Texts Me. For the millionth time.”.

José: [00:03:40] Yeah.

Ali: [00:03:41] It popped out to me.

José: [00:03:42] Yeah I’ll read it and then we can talk about it. My mom texts me for the millionth time. The phone vibrates, my mom buzzes my desk, her love reaches me wherever I am which is usually unavailable. My mom home with my family minus me might as well be my name. It’s our family’s second house in Calumet City after the first was lost to anachronisms. You can find my mom on the couch, her shoes off, her bare feet throb with her American ache, her work will wake her in a few hours to frame a store. My mom’s work is turning sanitary into pristine, but you already know my mom’s work by its invisibility. My mom’s shopping with you watching you, spill Mountain Dew on her floors, my job takes me away from home so I can build a bridge back to the living room. Where my mom rests her feet awash in the glow. She makes so effortless, it’s impossible to tell. The light comes from her own body. So in this poem. I think something that I’m kind of always grappling with is how, in order to build the life that I want in order to live the life that I love most, it takes me away from my family constantly. You know I went to school at Harvard University and so I left my family to go to college and then I left to find work in New York and I moved back and now I’m leaving again and my work is kind of constantly pulling me away. And at the same time it’s what allows me to build that bridge back again. What I’m hoping for right. Like I’m trying to reconnect.

Ali: [00:05:30] What I took away from this is that. It wasn’t that you were texting your mom a million times she was texting you so she was, you know, reaching out, right. Yes. In some ways you don’t even say that explicitly in the poem but you say it explicitly in the title. The text was you reaching out but the headline was, OK, she’s trying to find me.

José: [00:05:49] Yeah. And She always is. And she’s, you know, it always kind of stuns me like every time I’m in need of like a kind word or something my mom texts me and asked me how I am. And yes, so absolutely yeah. My mom, you’re right, my mom is trying to find me in the poem and the poem is me trying to find her back and so I’m picturing where she’s at that moment.

Ali: [00:06:12] So, has she read this?

José: [00:06:13] So my mom only speaks and reads and writes in Spanish. So you know my mom has the book and I’ve told her about the book and my mom knows that there’s poems about it but she hasn’t necessarily read the poems word for word.

Ali: [00:06:28] What do you think a reaction will be to this?

José: [00:06:30] I think my mom is always very proud of my work as a writer. I think also she’d probably get a little bit embarrassed. You know I think I get some of my shyness from her. So, you know, my mom would be a little bit shy that there are poems about her in the world.

Ali: [00:06:47] What does your dad think about your work?

José: [00:06:49] My dad is also a big supporter of my work. Again our relationship is not the most like emotionally communicative.

Ali: [00:07:01] I’m South Asian. I have the same thing.

José: [00:07:03] Yeah. So my dad tells me he loves me because he provides for our family. You know what I mean?

Ali: [00:07:08] Right.

José: [00:07:09] So my dad supports me. He shows up and he comes to the readings but we haven’t had yet a ton of conversations about the poems. That’s something that I’m hoping for that we’ll be able to talk more and more.

Ali: [00:07:20] That’s a process right? It’s a process.

José: [00:07:22] Yeah.

Ali: [00:07:23] You’re the one I want to talk about a little bit and kind of goes back to the journey question is “My Family Never Finished Migrating We Just Stopped.”

José: [00:07:30] All right. So I’ll read this one then we can talk about it. “My Family Never Finished Migrating We Just Stopped.” We invented cactus, to survive the winters, we created steel. At my dad’s mill, I saw a man dressed like a Martian walk straight into fire. The flames licked his skin, but like a pet it never bit him. In the desert, they find our baseball caps, our empty water bottles, but never our bodies. Even the best ICE agents can’t track us through the storms. But I have a theory. Some of our cousins don’t care about L.A. or Chicago. They build a sanctuary underneath the sand, under the skin we shed so we can wear the desert like a cobija under the bones of our loved ones, bones worn thin as thorns to terrorize blue agents. Bones worn thin as guitar strings. So when the wind blows, we can follow the music home. So, this one the origin kind of was a different place than where the poem ultimately went. What I was thinking about was this argument that you sometimes hear people on the right make where they say like well if America is such a terrible place then why is everyone rushing to get here, right? And when I wrote the title it was trying to articulate this idea that my family didn’t come to this country because of some innate American superiority to the rest of the world. My family will continue to migrate and so we find the place where we are safe until we find the place where we can be home and take care of each other and not be threatened, right? So it’s not that America is the ultimate end point in our journey is not to any one country, right? Our journey is to this place like I said where we can be safe and hold. And I was thinking about all of the stories about Juan Does that you read about and Juanita Does. Basically these are people who die crossing the desert in the United States and, by the time that their bodies are found, they’ve decomposed a lot of times so much that they’re unidentifiable there’s no records of who they are. And all we have left of them are these like very small artifacts. And so that’s why they’re called Juan Doe Or Juanita Doe because they’re unidentified, right? And so I was thinking about these stories and trying to find a way to imagine a different ending to that right. So maybe instead of vanishing into death maybe they found this place where we’re migrating towards and it’s underneath the sand and it’s a place where it’s safe from, you know, whatever people might threaten us.

Ali: [00:10:08] When I read it that’s what popped in my mind is the Juanita Does. Over the weekend, I was in Nogales across today. I was walking around the Sonora side and it brings it all to stark relief and that’s a city or town environment, but you get a very clear sense of why people are migrating.

José: [00:10:27] Yeah. And again that’s something that I think about a lot is migration is natural. It’s something that so many of us do, you know, within the United States for a variety of reasons. I moved from Calumet City to Cambridge in order to go to college. That migration is a natural thing that we do when we get an opportunity when we have to, we find ways to do it and continue to.

Ali: [00:10:52] Yeah, you teach poetry now.

José: [00:10:53] Yeah.

Ali: [00:10:53] So what’s that like?

José: [00:10:53] Teaching poetry is one of my favorite things. I love in a poetry workshop. Part of the work is facilitating the writing of poems. But part of the work is taking a look at Master texts and reading them together in kind of identifying the moves the writer is making. And I think about poetry the way that I think about magic in that the work is trying to transform ordinary objects. You take the ordinary material of your life and you try to transform it into something else so that you can reveal something deeper about what it means to be human about our relationships with one another about our relationships to work in the planet and so on. So for me, getting to see people who are beginning to write, see that happen in a poem and then begin to think about where that magic is for themselves that’s like one of my favorite to see them do that and then to hear them speak it and articulate it.

Ali: [00:11:51] And do you feel like for you as a poet, the ordinary if you will to use your term, is the immigrant experience the migrant experience? Is that part of it?

José: [00:11:59] I think that’s definitely part of it. I think so many of the poems in my book are reaching towards my parents because that’s kind of the unsayable, right? For me, right now. If I could say it easily then I would. But one of the things that I can’t articulate is the debt that I have to my parents. One of the other things that I think about right is when I was 16, I’ve went back to Mexico for a month and my secret plan was kind of to go to Mexico and stay because, you know, in my experience in public schools in the United States, I was like I don’t belong here, but if I could just go back then I would find where I belong and my life would make sense. But of course I went back to Mexico and they were like, Who are you?

[00:12:42] Right.

[00:12:43] You’re not one of us. You’re from El Norte, whatever. And so sometimes it feels like I was kind of cheated out of an experience back in my parents hometown and other times it feels differently. So there’s all of these things that are kind of constantly shaping how I see the world, how I interact with the world. So that’s kind of what I’m trying to illustrate in the poems.

Ali: [00:13:06] I sensed a lot of hope, fear, frustration, but rarely did I sense a lot of anger.

José: [00:13:13] Mm hmm.

Ali: [00:13:14] Is that true?

José: [00:13:15] I think that is true. And so this is. Another thing that kind of happened in the process of crafting the book right. Was the first manuscript was a lot more angry and sorrowful than what ended up becoming the book. And the reason for that is. I have three younger brothers. I want to make sure that when they read it they knew that I didn’t just see the parts of us that are sad or angry or you know kind of troubled that I also saw how funny we are. The book is dedicated to my three younger brothers and it’s because for better and sometimes for worse it’s like there’s nothing that they won’t make fun of. Like someone could be sick and hurting and my brothers will still find a way to make them laugh like they are always cracking jokes. And I wanted the book to reflect that. I don’t think about being Mexican or being the son of. Mexican immigrants as a burden. I’m not sad about that. I wake up happy and grateful for my experience.

Ali: [00:14:15] But you don’t romanticize the experience either. I mean it comes across the title of the book right? Citizen Illegal.

José: [00:14:20] Yeah, I did that on purpose, you know, because one, I understood that they were going to be people who would see the title, who would see my name and immediately already project a certain story onto the book. I didn’t need to then amplify that story arc to kind of play with those expectations. To write a story that’s funny or to write a story that’s not romanticized.

Ali: [00:14:44] So one funny small bit, vapor rub.

José: [00:14:47] Yes.

Ali: [00:14:49] I’ll let you read it and then we can we can have an entire like four-hour conversation around Vicks vapor rub.

José: [00:14:54] This poem it’s called No Vaporu. Vaporu is pronounced, vaporu like loud or chew. The label for Vaporu says it’s for cough suppression, but in my house vaporu is for headaches, sore muscles nightmares, and everything else. Put some vaporu on my dad’s diabetic toes and watch the Sugar evaporate. Miss a day of church, put some light blue on your head and watch forgiveness flushed your cheeks. Put some vaporu on our bank account and watch the bill collectors stop calling. When I forget a word in Spanish, take a teaspoon of blue under the tongue.

Ali: [00:15:37] Every immigrant household I think has the vaporu or vapor rub.

José: [00:15:41] Yeah, you know that’s been one of the cool experiences is that I thought that that was like a specifically Mexican thing. I didn’t know that it translated across a bunch of different cultures. That’s been cool to this day. Whenever I tell my mom that I’m sick, she’s like, mijo go buy some vaporu, you already know. That’s how you take care of it. This stuff is great.

Ali: [00:16:04] It is magic.

José: [00:16:05] Yeah it works.

Ali: [00:16:06] It works for everything.

José: [00:16:10] Yeah.

Ali: [00:16:10] A recurring Title of poems throughout the book is Mexican heaven. Yeah. And I ask you to read whichever one is your favorite one.

José: [00:16:18] But what I liked about it is that each one had the same title with kind of a different message. Yeah right.

Ali: [00:16:24] Which one is your favorite?

José: [00:16:26] So Mexican Heaven. I originally wrote as one long poem though read different parts. And I split it up for the book because it was my favorite poem in the book and I didn’t want to put it at the end because then what if people never got to the end. And then they missed my favorite poem and I didn’t want to put at the beginning because then they read the first poem and. I mean I really loved the book but then they never come back to that poem right. So what I wanted was to set it up so that no matter where you were in the book you were always coming back to Mexican Heaven.

Ali: [00:16:59] As I was reading it. I was like I wonder when the next one is gonna come.

José: [00:17:03] So I split it up for the book. So in terms of my favorite section, it changes from time to time. I think my favorite one is the Mexican Heaven on page 22. All the Mexican women refused to cook or clean or raise the kids or pay bills or make the bed or drive you to work or do anything except watch their novelas. So heaven is gross. The rats are fat as roosters and the men die of starvation.

Ali: [00:17:38] Why that one?

José: [00:17:39] I like it because one of the things that was on my mind as I was writing the book was the culture of machismo. And so this idea of there being a heaven where because the women refuse to do all of this work, that it’s kind of expected of them in our households, that heaven is gross. And the men die of starvation. I just I like that flip I like. You know I was proud of myself for that one.

Ali: [00:18:05] Yeah yeah yeah.

José: [00:18:06] Yeah.

Ali: [00:18:07] It kind of goes back to the first one that we talked about of your mom texting you for the millionth time.

José: [00:18:11] Yeah.

Ali: [00:18:11] Right. It’s not quite a start, but similar, similar theme.

José: [00:18:15] Yeah absolutely.

Ali: [00:18:17] Before we started I told you about a conversation I had with Monica Castillo who was a film critic. I was really looking at the role of immigrants in film and she had a really interesting perspective on storytelling of the immigrant experience I wanted to get your input on. To paraphrase she said so many stories about immigrants are about the journey or their arrival. But not necessarily about the departure. And why people leave. So I don’t know, I want to get your take on that.

[00:18:45] I like that. That sounds true to me and I think part of it goes back to what we were saying early on in our conversation where there’s a lot of shame about why people depart. Right and there’s like a lot of pain about why people depart that, you know, so many of us and so many of our parents write when they arrive. That’s the triumphant part right that hopefully is the beginning of something else. And so I think there’s an eagerness to bury what forces people to leave in the first place.

[00:19:19] Yeah, you’re absolutely right. Describe to me the cover.

[00:19:22] Yeah absolutely. So the cover art is by an artist from Phoenix, Arizona, who is now based in Chicago named Sent Rock(?). The cover of the book is one of sent Rock’s iconic figures and a figure that he paints over and over again. It’s a person wearing a bird mask. And in this instance, the person wearing the bird mass also has a halo around their head. They’re also tattooed, they have the rosary beads, they’re carrying a bottle of drink, you know, they’re surrounded by imagery that reminds of Chicago and the desert and there’s the Mexican eagle with the snake, so it’s all of these images said right. Is an artist that I’ve admired for a long time. Shout out to Sent Rock. And I knew, from the moment that I was writing this book, that I wanted to have a Sent Rock cover because that character that Sent Rock paints feels so on point. Kind of what I imagine to be the experience of immigration and the experience of kind of striving in America right like we’re ordinary people but we’d like try to wear the bird mask and we try to find our paths and we try to like fly and take off as much as we can. And so there’s something like very human and very hopeful and something there that has always captured me. So I was really lucky. I gave Sent Rock a bunch of the poems that are in the book and he created this image specifically for the cover so this is an original work of art.

Ali: [00:20:51] Oh really.

José: [00:20:52] Yeah absolutely yeah. And now we’re like good friends. I’m hopeful that we’ll keep collaborating on different projects.

Ali: [00:20:58] It’s a beautiful piece.

José: [00:20:59] Yeah.

Ali: [00:21:00] I got one last question for you.

José: [00:21:01] Go ahead.

Ali: [00:21:02] Finish the sentence and you know as a poet you’ve got a lot of pressure.

José: [00:21:07] Oh Lord, see you could have told me this beforehand.

Ali: [00:21:08] I’d never tell anybody this. So but at least I’m building it up. So I ask everybody to finish this sentence. Only in America dot dot dot.

José: [00:21:19] Let me see. Only in America do we celebrate the food and culture of immigrants while incarcerating and seeking to remove immigrants themselves.

Ali: [00:21:39] Thank you. I really really appreciate it.

José: [00:21:42] Thank you for having me.