The U.S. economic growth is outpacing growth in workers. As a result, labor shortages are projected to grow and that will act as a brake on the economy. We are already seeing inflationary fears stoked by labor shortages, and in some regions of the U.S., businesses are postponing plans for expansion due to lack of workers.

The crucial role immigrants play in our workforce is unfamiliar to many members of the public. Immigrants are projected to provide the bulk of growth in our workforce in the coming 40 years. To meet the goal of an annual GDP increase of 3 percent, immigrant workers will be essential. This fact sheet is the first of a seven-part series examining the role immigrants play in our labor force and the contributions they make to our economy. The document highlights research showing that immigrants and U.S.-born workers do not compete against each other for jobs, but rather, fill different niches in our economy.

Workers gravitate to different industries

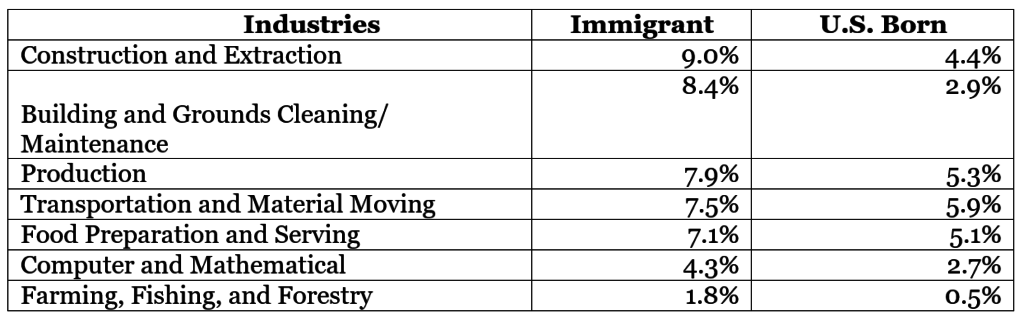

U.S.-born and immigrant workers are employed in disparate jobs within our workforce. Seven industry categoriesemploy nearly half (46.1 percent) of immigrant workers, but only a little more than a quarter (26.7 percent) of U.S. born workers.

Source: Current Population Survey, U.S. Census Bureau

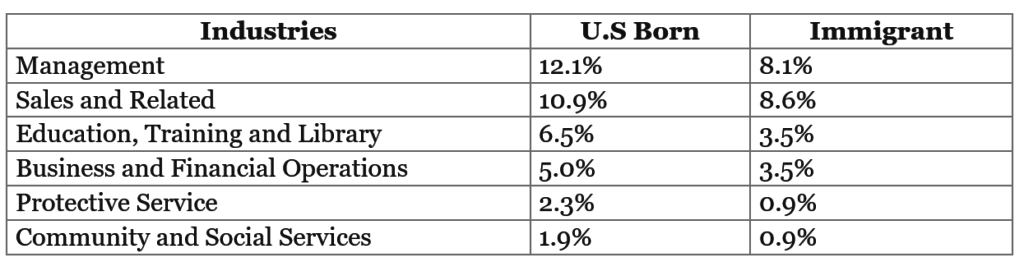

Source: Current Population Survey, U.S. Census Bureau

A different set of industry categories employ more than half (51.6 percent) of the U.S.-born workers, but only a third (33.6 percent) of immigrant workers.

Source: Bipartisan Policy Center

Source: Bipartisan Policy Center

U.S.-born and immigrant workers hold jobs requiring different skills

On average, U.S.-born workers tend to have higher levels of education and skills than immigrant workers do and, as a result, they work in jobs that require higher levels of education and skills and pay higher wages. Among the industries dominated by U.S.-born workers, 54 percent of them require a college degree or higher and median annual salaries are $50,000. In contrast, only 6 percent of the predominantly immigrant fields require a college degree or higher and median annual salaries are $36,000. The salary difference leads to further segmentation of immigrant workers and U.S.-born workers in the workforce. A highly-skilled, well paid U.S.-born worker will likely be less interested in a job that pays less and requires less in education and skills.

Immigrants are more likely to work nontraditional hours

Another difference between immigrant and U.S.-born workers is the hours worked. Immigrants are significantly more likely to work nontraditional hours than U.S.-born workers. Immigrants are 15 percent more likely to work, during the week, between the hours of 8:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m., and any time during the weekend. During weekend shifts, in particular, immigrants are 25 percent more likely to work weekends than U.S.-born workers are. The difference is due partly to the type of job that immigrants gravitate toward such as building maintenance. However, even in occupations where immigrants and U.S.-born workers fill the same jobs— for example, physicians and healthcare support workers — immigrants are more likely to work nontraditional hours.

Higher immigration levels correspond to higher employment rates for all

If immigrants were taking jobs from the U.S.-born, the expectation would be that areas with high levels of recent immigration would also have high unemployment rates. A study conducted in 2009 found there was little apparent relationship between recent immigration and unemployment at the regional, state, or county level. For example, in counties with the lowest percentage of recent immigrants (below 4.8 percent), unemployment averaged 4.6 percent. In counties with the highest percentages of recent immigrants (above 13.4 percent), unemployment was 3.1 percent. The same study found that unemployment tended to be higher in rural areas, which had fewer recent immigrants compared to urban areas, with more recent immigrants and lower unemployment.

A similar picture emerges if you look at the ebb and flow of immigration over time. One study compared the national unemployment rate to the immigration rate going back to 1890. In years when the number of immigrant arrivals was above the long-term average, the unemployment rate averaged 5.72 percent. In years where immigration was below the long-term average, the unemployment rate was higher, 7.17 percent. In sum, a long-term view of immigration shows that unemployment is lower during periods of high immigration.

Decline in U.S.-born labor market participation is not due to immigration

Much attention has been paid to the decline in labor participation rates of U.S.-born workers, especially since the 2007 recession. Some have questioned whether the decline is due to competition from immigrant workers. The answer is that U.S.-born workers have other choices, besides participating in the labor market.

- Retirement: Between 2000 and 2015, the retirement rate for the U.S.-born was higher than the retirement rate for immigrants. For example, the retirement rate for the U.S.-born population aged 65 and older in 2015 was 74 percent while the retirement rate for immigrants was 71 percent. Immigrants tend to have less in savings than the U.S.-born, and their Social Security benefits tend to be less than the U.S.-born. Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for Social Security benefits.

- Educational opportunities: Between 2000 and 2015, post-secondary enrollment among the U.S.-born increased by 2.1 percent, while among the foreign-born, it dropped by 0.1 percent.

- Disability: Between 2000 and 2015, the disability rate among U.S.-born workers increased by 2 percent, while it remained flat among the foreign-born. Immigrants are less likely to qualify for the two major disability benefit programs. Only citizens and lawful permanent residents (LPRs) are eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits, with rare exceptions. Eligibility for Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) is based on earned credit hours determined by work history. Immigrants, who generally have shorter U.S. lifetime work hours, are less likely to meet the credit hour minimums.

Labor shortfalls underscore the need for immigrant workers

Today, some of the industries that are heavily populated by immigrant workers are experiencing labor shortages, something that would not be expected if immigrants and U.S.-born workers were competing for scarce job openings. For example, in the construction industry, 63 percent of homebuilders reported labor shortages in a 2017 survey by the National Association of Home Builders. Worker shortages are common in construction and other predominantly immigrant industries, thus contradicting the theory that limiting immigration results in opportunities for U.S.-born workers.

The economy is not static

The idea that immigrants take jobs from U.S.-born workers is part of a view that the economy is static, the number of jobs is set, and an immigrant gaining a job means a U.S.-born worker loses a job. Economists find that the economy is dynamic and, when one person takes a job, other jobs are created. That newly employed person spends money on groceries, goes out to eat, buys clothing, and that extra demand for goods and services creates new jobs for other workers.

One 2015 study looked at understanding and improving the H-1B temporary immigrant workers program. H-1B workers are highly-skilled and highly-paid with many working in the technology industries. The study found that each H-1B worker was associated with an additional 1.83 jobs for U.S.-born workers. The same study cited the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which found that increasing the migration of highly skilled workers to the United States would generate $100 billion in economic growth over the next decade. Another study found a one percent increase in a city’s total employment of foreign STEM workers resulted in wage increases of 7 to 8 percent for U.S.-born college educated workers, and a 3 to 4 percent increase in wages for non-college educated workers — a significant boost to our economy.

*Special thanks to Maurice Belanger for his contributions to this series.

To see all papers in the Immigrants as Economic Contributors series, click here.

Economic Contributors I: Complementing not Competing PDF

Author: Dan Kosten