Immigrants are increasingly pivotal in the U.S. economy. Not only do they provide a more permanent solution to our workforce needs, but they also help fill the temporary needs of American employers. This paper is part of a series examining the immigrants’ various roles in our economy. It highlights research on immigrants employed as temporary workers, who fill the labor needs of U.S. employers that experience temporary or seasonal spikes in business. The paper also shows how some longer-term nonimmigrant temporary workers have become critical to the workforce of businesses with longer-term labor needs that have not been met by the native-born workforce or by our outdated immigrant visa system.

Temporary Visas Are Critical to the U.S. Economy

Two types of visas exist for foreigners who want to enter the United States: an immigrant visa, which provides permanent resident status and could lead to citizenship, and a nonimmigrant visa, which provides foreigners with authorization to stay only temporarily. Nonimmigrant visas are granted to foreigners coming to the U.S. for tourism, diplomatic purposes, and temporary work.

Thousands of temporary worker visas are allocated each year, divided into about 20 categories. Some are allocated for seasonal work, and some are issued for longer periods to fill worker shortages employers’ face. Some of these temporary visas, however, are capped in the number that can be allotted each year. These caps can pose a challenge for certain sectors of the economy that cannot get enough workers for the jobs they have open.

For the most part, the immigrants on temporary work visas are working full-time and must return to their country after their visa expires. This paper focuses on the most significant of these 20 temporary worker visa categories.

Seasonal Workers in Agriculture

Some farmers, by the nature of their business, have labor needs that vary depending on the season. Crop farms, for example, will need many more workers during harvest season. Farmers often cannot find enough native-born workers who are willing and available to fill these jobs.

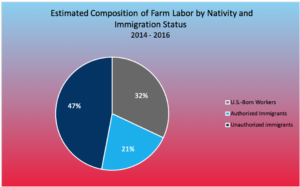

While employers in the agricultural industry require workers to provide work authorization documents, experts estimate that unauthorized workers comprise a significant percentage of their workforce. For example, approximately 50 percent of hired crop farmworkers are unauthorized immigrants. Nevertheless, in the last 10 years, the number of unauthorized Mexican workers available to work on U.S. farms has declined. U.S. farmers are increasingly turning to the H-2A seasonal agricultural work program, an initiative specifically designed to provide agricultural workers during periods of peak demand.

Source: USDA Economic Research Service, “Farm Labor,” https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/

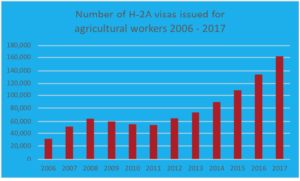

Employers participating in the H-2A program must show the government that they are hiring foreign workers only when native-born workers are unavailable. They must show that they attempted to recruit U.S. workers. In addition, they must provide housing to immigrant workers from outside the area. Employers must also pay, at minimum, a wage the government calculates based on compensation rates for similar jobs in a specific region. That way wages, in that occupation, will not be depressed (or “adversely affected”) by the hiring of temporary H-2A workers. Despite these requirements, farmers cannot find sufficient U.S. workers and rely on the H-2A program to get their work done. The number of temporary workers coming to the U.S. with H-2A agricultural work visas has more than quintupled in the last decade, from approximately 31,000 in 2006 to more than 160,000 in 2017.

Source: Department of State, Nonimmigrant Visas by Individual Class of Admission (various years) https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/legal/visa-law0/visa-statistics/nonimmigrant-visa-statistics.html

Some agriculture employers have complained that the H-2A temporary worker program does not adequately meet their labor needs. While there is no numerical cap on H-2A visas, farmers cite burdensome regulations, a system that is unable to keep up with the demand for labor in a timely manner, and the ineligibility of agricultural industries that need year-round workers, such as the dairy industry. The H-2A visa is in need of reform so that it can better meet the needs of the agriculture sector, in a timely manner, while maintaining adequate labor protections for farmworkers.

Seasonal Nonagricultural Workers

Thousands of nonagricultural employers also have spikes in seasonal labor demands. These employers can turn to the H-2B temporary worker program when they cannot find enough U.S. workers who are willing and available to fill their temporary needs. The H-2B program provides visas for temporary workers who are coming to the U.S. to perform seasonal nonagricultural work. These workers are typically employed in the landscaping, hospitality, resort, or other industries that have peak seasonal needs. Employers seeking these workers must first attempt to recruit U.S. workers. They must provide the same conditions and pay to foreign workers that they would provide to U.S. workers, in the same positions, to ensure they do not undercut the wages of U.S. workers.

However, unlike the H-2A program for agricultural workers, which is uncapped, the H-2B program is currently capped at 66,000 visas per year. In the H-2B program, 33,000 visas are reserved for workers who begin employment in the first half of the government’s fiscal year, and the other 33,000 for workers who start in the second half. The H-2B visa cap is inadequate to meet the high demand for workers. For example, the government began receiving H-2B petitions on February 21, 2018, for the 33,000 H-2B visas allocated for the second half of fiscal year 2018. After five business days, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) had received petitions for 47,000 workers. All H-2B visas are allocated by lottery. Employers get the workers they need — or not — literally by the luck of the draw.

Source: Office of Foreign Labor Certification, Annual Reports FY 2007, FY 2010, FY 2013, and FY 2016. The demand for these workers dipped during the recession but is on the rise again. https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/performancedata.cfm

For many employers with seasonal needs, failure to obtain H-2B workers forces them to cut back on operations, putting other jobs in jeopardy. One report estimated that 1 in 3 businesses that are dependent on H-2B workers would be forced to close or scale back their operations if they were unable to hire said workers. As a result, U.S. workers at those companies could lose their jobs. In plain terms, the ability of employers to hire these temporary immigrant workers helps secure the jobs of U.S. workers.

A Cultural Exchange Program That Provides Work Experience

American employers with seasonal temporary needs also benefit greatly from another initiative, the Summer Work Travel category under the J-1 Exchange Visitor Visa program. Summer Work Travel does not technically involve workers, but it allows foreign college students to work in seasonal or temporary jobs and experience U.S. culture while also meeting the temporary labor needs of U.S. employers. They travel to the U.S. on a J-1 visa.

The Summer Work Travel category is the largest of the J-1 visa categories. About 105,000 foreign students, or nearly one-third of all J-1 visa recipients in 2017, visited and worked in the country through the Summer Work Travel program.

These student workers are a valuable asset to employers in locations where the economy is seasonal, such as at national parks, summer recreational areas, and beaches. In some places, these workers make up a large percentage of the workforce. For example, J-1 Exchange Visitors make up approximately one-fourth of the workforce at Xanterra Parks and Resorts, a company that operates restaurants and lodging facilities at several national parks in the Mountain West.

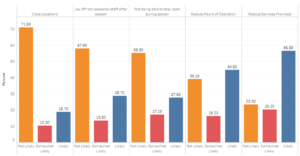

While these seasonal businesses also hire local college students, the schedules of the foreign students sometimes aligns better with seasonal demand. Employing J-1 visa recipients allows businesses to remain open for a longer season because the availability of foreign students is longer than that of local students. If businesses were to eliminate foreign workers, the consequences could include closure, layoffs, reduced hours, and/or reduced services, as illustrated in the graph below. Each of these results has a negative ripple effect throughout local economies.

Chart 3. Consequences if Host Business or Organization Did Not Employ Summer Work Travel Participants

Source: National Immigration Forum: Mutual Benefits: The Exchange Visitor Program (J-1 Visa), https://forumtogether.org/article/mutual-benefits-the-exchange-visitor-program-j-1-visa/ 20Report.pdf

Temporary Visas for Foreign Professionals

The H-1B visa is one of the temporary visa categories that is frequently debated when immigration reform efforts come up. This visa is for foreign professionals in specialty occupations. It is often referred to as a high-skilled or “tech” visa, though technology is not the only field for which this visa is allocated. This visa permits an individual to work in the United States for three years and, after that, the visa can be renewed for another three years. If the employer petitions for an employment-based immigrant visa (green card) for the worker, the worker may extend his or her temporary H-1B status beyond six years, in one-year increments, until a permanent visa is available.

An employer wishing to hire an H-1B temporary worker must first certify with the U.S. Department of Labor that the worker will not adversely affect U.S. workers in similar positions. A business will typically spend thousands of dollars in legal costs and government fees to bring in a temporary worker on an H-1B visa.

Immigrants with H-1B visas are employed in health care, business, finance, and other industries. However, the bulk of H-1B temporary workers are employed in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. The ability of employers to hire foreign professionals to fill employers’ needs is a boon to the economy. Every 100 H-1B workers employed are associated with an additional 183 jobs for native-born workers.

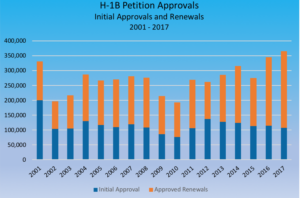

The technology revolution dating to 1990 has created a strong demand for workers with information technology skills, one that the U.S. workforce cannot entirely meet. When the current visa cap was set in 1990, the World Wide Web was in its infancy and neither smartphones nor social media were on the horizon. The use of technology, the internet in particular, has exploded since then, yet the cap on H-1B visas is stuck in the era of fax machines. Employers today file tens of thousands H-1B petitions, in excess of the 85,000 visas per year cap. These submissions occur immediately when the petition submission period opens, and USCIS holds the period open for a minimum of five business days. That figure includes 20,000 H-1B visas reserved for foreign students with a master’s degree or higher from a U.S. education institution. If more than 85,000 H-1B visa petitions are submitted, USCIS conducts a computer-generated random lottery to select the visa petitions.

However, the actual number of H1-B visas granted in any one year far exceeds the 85,000 combined cap. That is because visa requests from certain nonprofits, government research organizations, and higher education institutions are not included in the cap. And the growth in the H-1B visa program is due primarily to renewals by H-1B visa holders already in the country, which also are not counted against the cap.

Source: USCIS, “Characteristics of Specialty Occupation Workers (H-1B): various years,” https://www.uscis.gov/tools/reports-studies/reports-and-studies

Temporary Visas as a Workaround for a Broken Employment Immigration System

Many U.S. employers are looking to hire workers for permanent positions to keep their businesses operating. However, the number of permanent visas provided to those coming to work in the U.S. has not changed since 1990 — even though the size of the U.S. economy has tripled in that time. Relatively few immigrants come to the U.S. on permanent work visas. A maximum of 140,000 permanent work visas are granted each year in five separate categories, but that number includes the spouses and children of workers, so the number of visas allocated to actual workers is lower.

As a result of quotas remaining the same for employment-based permanent visas, employers have increasingly turned to the use of temporary visas to fill their workforce needs. The backlog for a permanent visa can cause a wait of many years. For example, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is just now processing visa applications filed in March 2009 by Indian nationals under the visa category reserved for “Professionals Holding Advanced Degrees.” Both worker and employer must endure the uncertainty inherent in the annual filing of the extension for the temporary visa.

The United States must reform the immigration system to stabilize the workforce. Our immigration system can help address the U.S. workforce needs of the 21st century, if we make the necessary changes.

To help alleviate worker shortages in STEM fields, the government should allow more foreign students to remain in the country after their studies at U.S. colleges and universities. In 2013, approximately 77 percent (26,530) of the full-time graduate students in electrical engineering and 71 percent (27,787) in computer science at U.S. universities were foreign students. Unless they can get an H-1B visa or a permanent visa, these students must return to their home country, and employers lose access to nearly three-quarters of the U.S.-trained students in these fields.

Conclusion

In today’s economy, businesses face difficult challenges in securing workers they need to help maintain and grow their businesses. This paper illustrates the importance of nonimmigrant or temporary visas for employers to fill temporary labor needs when they cannot hire enough U.S. workers. Whether they work in agriculture, at national parks, or at a tech startup, immigrants with temporary visas are critical to the U.S. economy. If the current demand for these workers is any indication, they will be in even higher demand in the future.

Our permanent-employment-based immigration system is out of date, which also forces employers to rely increasingly on temporary work visas to employ workers whom they would like to hire for permanent positions. The demand for workers has grown with the economy. Fiscal growth has outpaced growth in the native-born workforce, resulting in employers seeking out immigrant labor. Yet our immigration policies have remained stuck in the past. Going forward, our economy will require an employment-based immigration system that is far more aligned with our economic needs.

*Special thanks to Maurice Belanger for his contributions to this series.

To see all papers in the Immigrants as Economic Contributors series, click here.

Economic Contributors – Temporary Workers -PDF

Author: Dan Kosten