The United States faces a growing challenge related to illicit fentanyl. As the challenge grows, the conversation often turns to drug smuggling into the U.S. and how the situation at the U.S.-Mexico border enhances the problem. Illicit fentanyl has devastating impacts across all corners of the United States, causing public health issues in thousands of American communities large and small, from the southern border to New England, and the Pacific Northwest to the Midwest. To provide solutions to this challenge, it is important to acknowledge and have an accurate perspective of how illicit fentanyl and drug smuggling interacts with U.S. borders.

I. Drug Seizures at the Border: By the Numbers

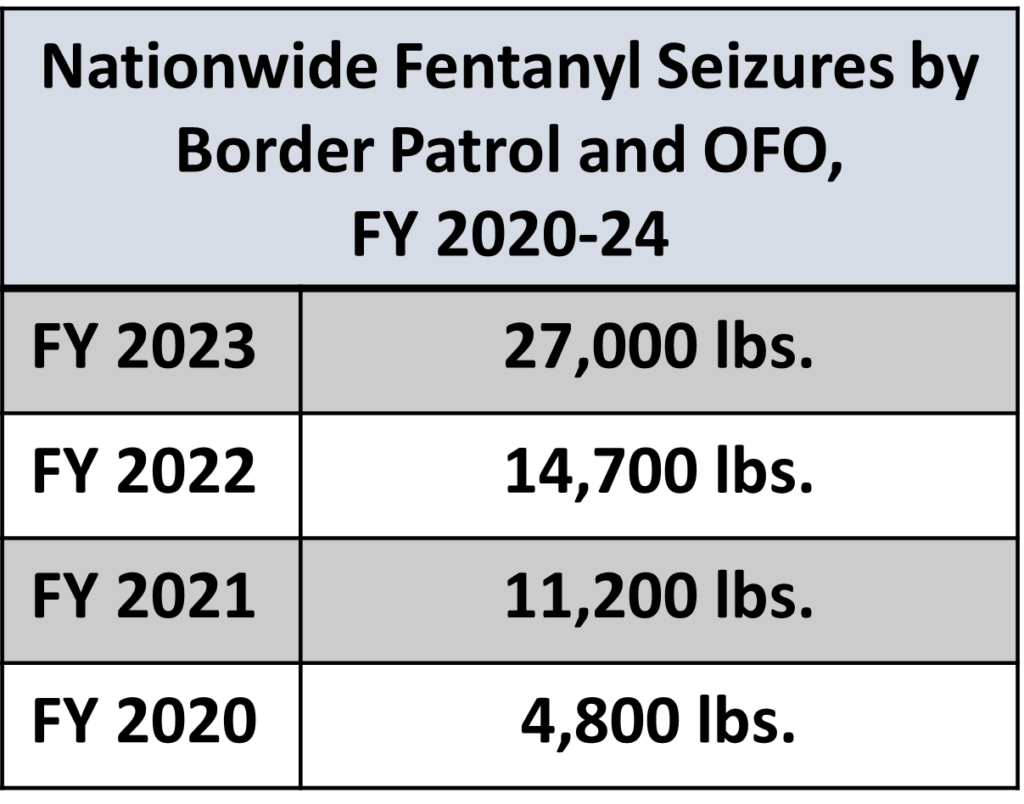

Data indicates drug seizures at the U.S.-Mexico border, by pounds seized, are trending down. The good news, at closer look, can be misleading. Seizures of heavier, less-potent drugs like marijuana are down while illicit fentanyl, a drug 100 times more potent than morphine, are up significantly: 480 percent higher at the southern border in fiscal year (FY) 2023 compared to FY 2020.

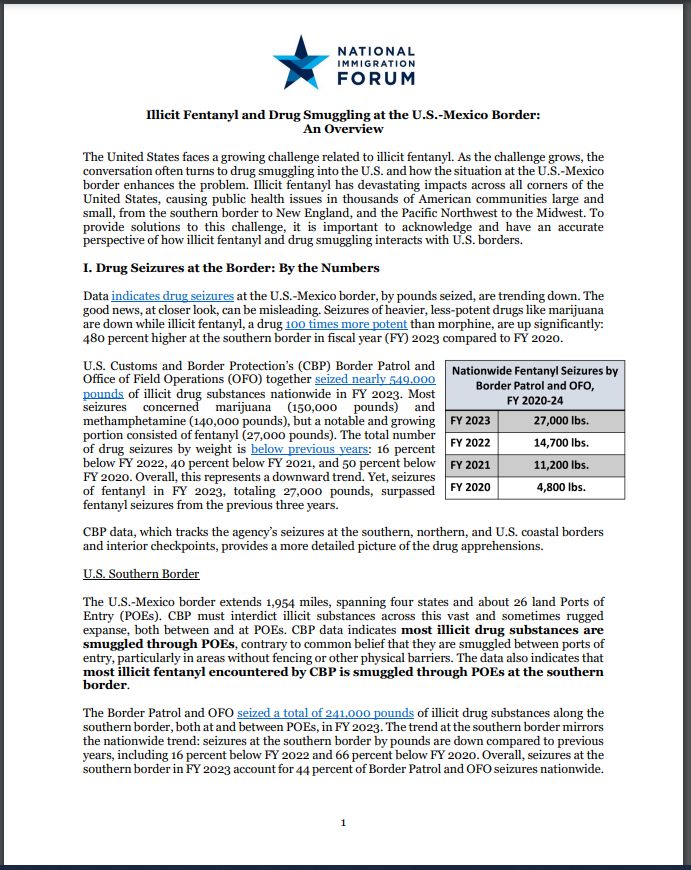

U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Border Patrol and Office of Field Operations (OFO) together seized nearly 549,000 pounds of illicit drug substances nationwide in FY 2023. Most seizures concerned marijuana (150,000 pounds) and methamphetamine (140,000 pounds), but a notable and growing portion consisted of fentanyl (27,000 pounds). The total number of drug seizures by weight is below previous years: 16 percent below FY 2022, 40 percent below FY 2021, and 50 percent below FY 2020. Overall, this represents a downward trend. Yet, seizures of fentanyl in FY 2023, totaling 27,000 pounds, surpassed fentanyl seizures from the previous three years.

CBP data, which tracks the agency’s seizures at the southern, northern, and U.S. coastal borders and interior checkpoints, provides a more detailed picture of the drug apprehensions.

U.S. Southern Border

The U.S.-Mexico border extends 1,954 miles, spanning four states and about 26 land Ports of Entry (POEs). CBP must interdict illicit substances across this vast and sometimes rugged expanse, both between and at POEs. CBP data indicates most illicit drug substances are smuggled through POEs, contrary to common belief that they are smuggled between ports of entry, particularly in areas without fencing or other physical barriers. The data also indicates that most illicit fentanyl encountered by CBP is smuggled through POEs at the southern border.

The Border Patrol and OFO seized a total of 241,000 pounds of illicit drug substances along the southern border, both at and between POEs, in FY 2023. The trend at the southern border mirrors the nationwide trend: seizures at the southern border by pounds are down compared to previous years, including 16 percent below FY 2022 and 66 percent below FY 2020. Overall, seizures at the southern border in FY 2023 account for 44 percent of Border Patrol and OFO seizures nationwide.

Border officials at POEs must manage enormous amounts of trade and travelers. In just one month, in July 2023, OFO processed 16.5 million pedestrians, passenger vehicles, and cargo trucks along the southern border. At the same time, border officials interdict efforts to smuggle illicit substances into the U.S. In FY 2023, OFO seized 176,000 pounds of illicit drug substances at POEs, accounting for about 73 percent of the total amount seized at the southern border. The Border Patrol, which covers areas between POEs, seized the remainder 65,000 pounds, or 27 percent.

This data indicates most smuggling of illicit drug substances into the U.S. happens at ports of entry, not between. Hidden in compartments in vehicles and cargo, smuggling is often quicker and more expedient at POEs compared to traveling through rough terrain between ports. While it might appear easier to smuggle illicit fentanyl between POEs, there are tools that detect the movement of illicit drugs between ports that likely make it a more difficult option. These tools include the heightened presence of Border Patrol agents along the border and detection technology, including Integrated Surveillance Towers (ISTs), Land Interdiction Multi-Role Enforcement Aircraft (MEA), tunnel detection programs, and other radar and remote surveillance technology.

CBP data also shows illicit fentanyl smuggling is increasing, and that most of the fentanyl seized by the Border Patrol and OFO is coming across the southern border. Border officials seized 4,600 pounds of fentanyl along the southern border in 2020, a number that skyrocketed to 26,700 pounds in FY 2023 – a 480 percent increase. Most of the fentanyl seized by the two agencies in FY 2023, about 98.9 percent (26,700 out of 27,000 pounds), was seized at the southern border. The remaining 305 pounds were encountered at the northern border (2 pounds) and at U.S. maritime borders and interior checkpoints (303 pounds). Of the fentanyl seized at the southern border, the vast majority, about 23,900 pounds or 90 percent, was seized at POEs.

The fact that most illicit fentanyl is smuggled through POEs adds credence to nationwide evidence that illicit drugs are predominantly smuggled through land ports, not between. CBP’s data shows fentanyl smuggling to the U.S. is increasing, most of it is smuggled through the southern border, and a majority of that comes through ports of entry.

U.S. Northern and Maritime Borders

The U.S. border with Canada spans 5,525 miles, from Washington State to the tip of Maine and along Alaska’s eastern front. CBP must interdict illicit substances across this vast, northern border. In addition, CBP’s Air and Marine Operation (AMO) secures America’s maritime borders, deploying aircraft and maritime vessels to inspect cargo and confront possible threats.

CBP data indicates that drug seizures at the northern border are down compared to previous years, with 55,100 pounds seized in FY 2023 compared to 60,100 pounds in FY 2022 (an 8 percent decrease) and 84,900 pounds in FY 2021 (a 35 percent decrease). In this respect, seizures at the northern border mirror the downward trend at the southern border. However, unlike the southern border, seizures of illicit fentanyl at the northern border are miniscule, but also trending downward. CBP seized two pounds of fentanyl in FY 2023, compared to 14 pounds in FY 2022 (an 85 percent decrease) and 22 pounds in FY 2021 (a 91 percent decrease). While the data does not definitively answer why seizures of fentanyl at the northern border have been so infrequent, it is possible that illicit drug trafficking organizations are focusing their smuggling operations along the U.S southern and, increasingly, maritime borders.

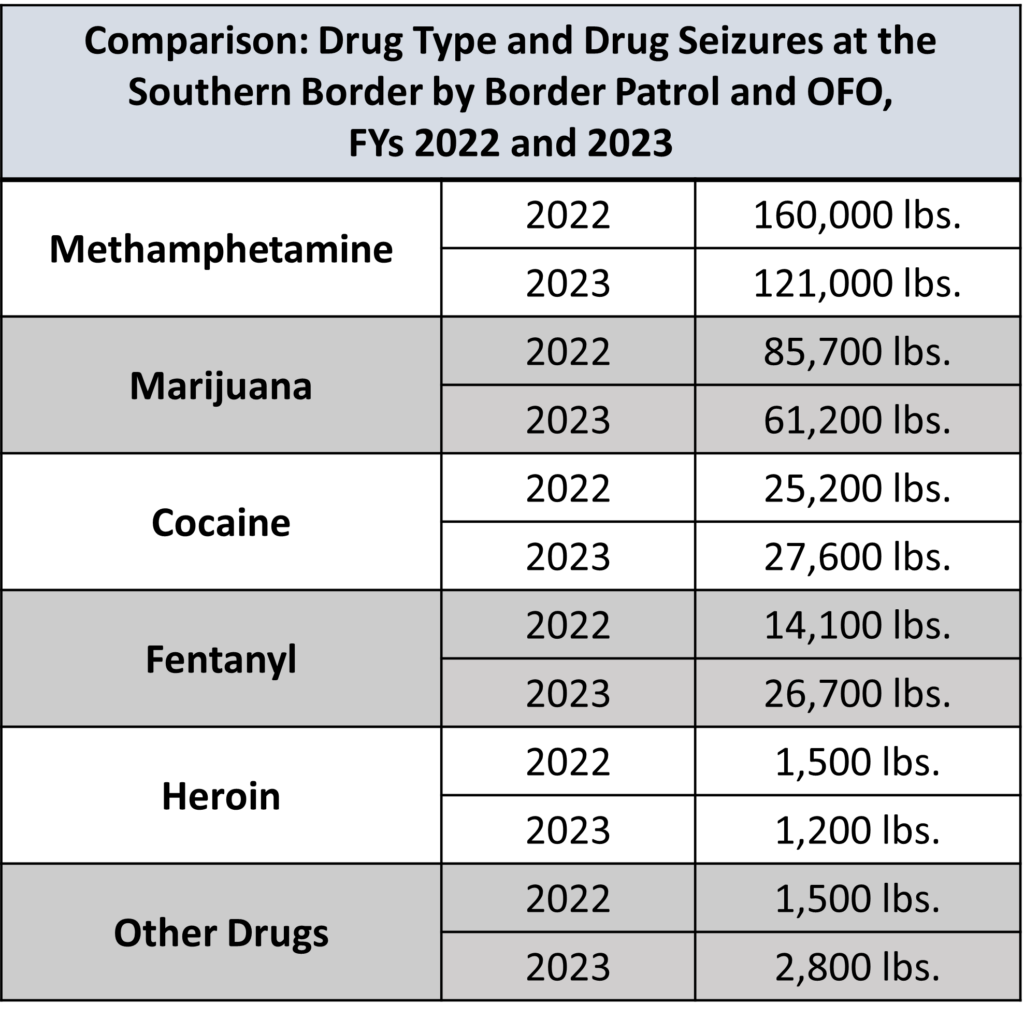

U.S. maritime borders are protected by CBP AMO, which includes 1,800 federal agents and support personnel responsible for interdicting migrants and unlawful cargo in maritime and air environments, as well as beyond the border in the interior of the U.S. AMO’s seizure data is kept separate from the Border Patrol and OFO numbers.

AMO seized a total of 304,400 pounds of illicit drug substances nationwide in FY 2023.[1] CBP’s AMO data does not indicate a downward trend in seizures by pound similar to the downward trends at the southern and northern borders, but rather points to an overall increase in FY 2023: higher than FY 2022 (270,400 pounds for the full year) and FY 2020 (287,400 pounds for the full year).[2] The data shows that seizures of illicit fentanyl increased significantly between FY 2021 and FY 2022, before increasingly slightly in FY 2023. There were 1,453 pounds of fentanyl seized in FY 2023. This is a small increase from seizures for FY 2022 (1,325 pounds or a 10 percent increase) and a significant increase from FY 2021 (786 pounds or an 85 percent increase). Fentanyl smuggling at maritime borders is likely to become a growing concern.

How Much Fentanyl Is Reaching the U.S.?

CBP officers and agents successfully interdict a significant amount of illicit drug substances smuggled into the U.S., but obviously cannot completely stop the flow of all drugs into the country. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) stated in December 2022 that the agency seized more than 10,000 pounds of fentanyl powder in the U.S. in 2022, while noting that “[m]ost of the fentanyl being trafficked by the Sinaloa and CJNC Cartels is being mass-produced at secret factories in Mexico with chemicals sourced largely from China.”

If law enforcement agencies working in the U.S. are interdicting illicit fentanyl made in Mexico, it is conclusive that illicit drug substances are being successfully smuggled into the country. While we do not have specific numbers on the amount that “gets away” or is not interdicted, it is important to consider that CBP and other border authorities may need additional resources to further stop the flow of illicit substances into the U.S.

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) noted in July 2019 that “[o]f the total amount of illicit drugs that reach the U.S. border by land, air, or sea… an unknown portion is successfully smuggled into the country.” CBP is the primary agency charged with safeguarding U.S. borders, but it is not the only agency that seizes illicit drugs, including at the border. Federal, state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies are involved in enforcement actions that may result in drug seizures. The CRS report notes that “there is no central database housing information on illicit drug seizures from all law enforcement agencies, federal or otherwise.” And, even with such a central database, its insight into successful drug smuggling might be imprecise. It is therefore hard to ascertain the amount of illicit drug substances successfully smuggled into the U.S.

II. Background on Fentanyl

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) describes fentanyl as a “synthetic opioid…a Schedule II controlled substance that is similar to morphine but about 100 times more potent.” There are two types of fentanyl. Pharmaceutical fentanyl is typically used under the supervision of licensed medical professionals to treat patients with severe pain – when properly used and prescribed it tends to pose little risk to patients. Illicitly manufactured fentanyl smuggled to the U.S., however, is typically produced in Mexico in clandestine labs with little to no oversight. Precursor chemicals for its manufacture largely come from China or India, though sometimes they also are made in the U.S. and smuggled south to Mexico.[3]

Illicit fentanyl is sometimes sold as a powder or a nasal spray. It may also be laced into other illicit drugs to increase the potency of those drugs or pressed into pills to look like legitimate prescription opioids. The DEA notes that, “[t]wo milligrams of fentanyl can be lethal depending on a person’s body size, tolerance and past usage.” How can we put that into perspective?

Fentanyl’s Potency

There are 1,000 milligrams in one gram of fentanyl, which turns out to be about 500 potential lethal doses (1,000 divided by 2) in just one gram. Each pound has 453.6 grams. When multiplied by 500, this comes out to about 226,700 potential lethal doses in one pound of fentanyl. This exercise is not an exact science, but it helps demonstrate the drug’s potency in small quantities. Of course, not every dose of fentanyl results in death, but increasing use of illicit synthetical opioids like fentanyl are exacting an enormous toll – killing 150 people each day according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Overall, between June 2020 and May 2021, more than 100,000 Americans died from a drug overdose.

Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking

Congress established a Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking in 2019 charged with examining the synthetic opioid threat to the U.S.[4] The commission published its final report in February 2022. The report examines the causes: it traces the origins of illicit fentanyl and other synthetic opioid misuse to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) approval of the prescription opioid painkiller OxyContin in 1995. As the report notes, “[p]eople with substance-use disorder, unable to continue obtaining prescription drugs, often turned to heroin and then – sometimes unknowingly – to powerful synthetic opioids.” In time, illicit criminal networks were producing and smuggling synthetic opioids to the U.S. Drug cartels quickly benefited from the rise of illegal synthetic opioids because they were and continue to be cheaper and easier to produce than other illicit substances, while being more difficult to interdict. As the Commission notes, “such a small amount goes such a long way, traffickers conceal hard-to-detect quantities in packages, in vehicles, and on persons and smuggle the drugs across the U.S.-Mexico border.”

The Commission’s report highlights the key concept of supply and demand. It determines that it is not possible to reduce the availability of illegal synthetic opioids like fentanyl by focusing on supply alone. In making this determination, the report considered the Mexican drug cartels’ financial and paramilitary strength, including “its use of violence against those who stand in their way.” The Commission found that, to “reduce illegal supply, the United States must also reduce demand,” including through public health awareness campaigns, expanded high-quality treatment programs, and intervention efforts to prevent fatalities.

Criminal Penalties

The DEA provides sentencing guidelines for those convicted of smuggling illicit substances across a U.S. border. Every sentence has a mandatory minimum and an accompanying fine. Mandatory minimum sentences and accompanying fines increase when the amount illicit substances carried across the border reaches a certain threshold, the trafficker has been caught trafficking drugs before, and/or the trafficking resulted in a serious injury or death. For instance, a first-time offense smuggling illicit fentanyl across a U.S. border carries a mandatory sentence of five to 40 years imprisonment and a $5 million fine. However, if the trafficking resulted in serious injury or death, there is a mandatory life sentence. If this was the second time the person was caught trafficking fentanyl, the mandatory minimum sentence increases to ten years to life in prison and a mandatory $8 million fine.

In federal judicial districts along the U.S. southern border, drug trafficking is one of the most prosecuted crimes. There are five districts along the U.S.-Mexico border. In fiscal year (FY) 2022, there were 1,827 drug trafficking charges in the Southern District of California (S.D. Cal.), accounting for 53 percent of all prosecuted crimes in the district. The other districts also had notable rates of trafficking prosecutions: 508 cases (or 12 percent) in the District of Arizona (D. Ariz.), 274 (13 percent) in the District of New Mexico (D.N.M.), 972 (16 percent) in the Western District of Texas (W.D. Tex), and 981 (14 percent) in the Southern District of Texas (S.D. Tex) were on drug smuggling charges. Drug trafficking prosecutions in S.D. Cal. are significantly higher than other judicial districts along the border, likely due in part to heightened CBP and other federal law enforcement presence in the district and San Ysidro being one of the busiest ports of entry in the U.S.

III. Fentanyl and the Border

Drug seizures at the U.S.-Mexico border, by pounds seized, are trending down, yet it is important to acknowledge that there is an increase in illicit fentanyl smuggling into the U.S. The challenge, however, is not purely an immigration issue. Illicit fentanyl is being smuggled predominantly by U.S. citizens and through ports of entry. Federal programs to stop the flow of fentanyl, when successful, ultimately focus on interdiction technology and targeted inspections.

Who Is Smuggling Illicit Drugs?

Evidence indicates that illicit fentanyl is primarily brought to the U.S. by American citizens and usually through legal ports of entry. The calculation is simple: illicit drug smuggling organization are likely to prefer U.S. citizens as smugglers because they are less likely to raise alarms or undergo additional vetting when re-entering the U.S. through a legal port.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission recently released an annual report on incidents related to fentanyl trafficking. In fiscal year (FY) 2022, 19,851 drug trafficking offenses were reported to the Commission. Of these, 2,362 (about 12 percent) were fentanyl-trafficking cases. This represents a steady increase since FY 2018, when there were only 422 reported offenders – an increase of about 460 percent in four years. The report shows that most fentanyl trafficking offenders in FY 2022 were U.S. citizens (88 percent). The vast majority were men (82 percent), with an average age of 35 years. A large proportion (40 percent) had little or no prior criminal history.

Data from previous years also indicates the significant role U.S. citizens play in fentanyl smuggling. In 2021, 86 percent of fentanyl trafficking convictions were for U.S. citizens. The Cato Institute also notes how just 0.02 percent of people (279 out of 1.8 million migrants) encountered by the Border Patrol for crossing unlawfully possessed fentanyl. While CBP and other border officials must deal with challenges at the border related to processing asylum seekers, the trafficking of fentanyl itself is largely connected to U.S. citizens.

CBP Interdiction Efforts

On March, 21, 2023, DHS announced a new coordinated effort, Operation Blue Lotus, to target the smuggling of illicit fentanyl into the U.S. Led by CBP and Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) agents, the operation reportedly stopped more than 900 pounds of fentanyl from coming into U.S. in just its first week. The operation included increases in targeted inspections conducted by CBP officers and HSI agents at ports along the border, as well as using canine units and advanced scanning technology to inspect cargo. By May 2023, Operation Blue Lotus and other efforts had interdicted more than 10,000 pounds of illicit substances. In one port of entry, the operation saw an increase of 2,000 percent in seizures and the arrest of 284 people on fentanyl charges. Operation Blue Lotus lasted from March 13 to May 10, 2023. DHS stated that the insights learned during the operations will enhance the department’s approach to interdicting illicit substances in the future.

The Biden administration has called in its FY 2024 budget request for additional resources to interdict illicit fentanyl and other illicit substances, including $305 million for non-intrusive inspection systems, with a primary focus on fentanyl detection at ports of entry. The budget also includes funding requests for CBP’s Forward Operation Labs (FOLs) at POEs, which conduct real-time analysis of unknown substances, enabling CBP to quickly identify unknown powders and other substances, and the Repository for Analytics in Virtualized Environment (RAVEN) program to help special investigative units identify, disrupt, and dismantle transnational criminal organizations and their networks.

IV. Recommendations

Border policies play a critical role in the interdiction of illicit substances being smuggled into the U.S. Yet, illicit fentanyl and opioids are far more than just an immigration or border issue. Tackling this problem will require a broad-based, comprehensive government response.

Included in that response, the federal government can take steps at the border to help tackle this challenge. Key policies and programs, some already implemented, can help stop the flow of illicit synthetic opioids along the U.S. borders:

- Advanced Technology at Ports. Authorize funding for targeted inspections conducted by CBP officers and HSI officers at ports of entry to stop the smuggling of illicit fentanyl and other illicit substances into the U.S. This element includes expanding on recent surge operations that stopped more than 900 pounds of illicit fentanyl from coming into the U.S. in a single week.

- Address the Demand for Illegal Synthetic Opioids. To reduce the availability of illegal synthetic opioids like fentanyl, the federal government must help reduce the demand for such substances, including through public awareness campaigns, expanded high-quality treatment programs, and intervention efforts to prevent fatalities.

- Bolster Inspections at International Mail Facilities (IMFs). Provide CBP and U.S. Postal Service with the authority and resources, including facility space and scanning technology, to screen and inspect incoming mail shipments. An oversight report from the U.S. Postal Service’s Inspector General found that postal inspectors interdict only a fraction of the drugs entering through the U.S. mail.

- Enhance Data Collection on Drug Seizures. Establish a central database housing information on illicit drug seizures by law enforcement agencies at the federal level, which would consolidate information and enhance data availability. Federal agencies could also incentivize state, local, and tribal law enforcement agencies to collect and report such data to help establish a more robust view of drug seizures in the nation.

- Hire Additional CBP Personnel. Provide CBP with funding to hire additional OFO officers, Border Patrol and AMO agents and support personnel to help interdict the smuggling of illicit fentanyl and other drugs into the U.S. Specifically, CBP should hire 600 new OFO officers and 100 more agriculture specialists annually until they reach staffing requirements identified each year in the agency’s Workforce Staffing Model. In FY 2019, OFO identified a need for 26,837 CBP officers and 3,148 agriculture specialists.

These recommendations can help play a positive, first step in stopping the flow of illicit substances into the U.S. and, long-term, in reducing the overall demand for illicit synthetic opioids.

Conclusion

The U.S. must find innovative solutions to stop and reverse the prevalence of illicit fentanyl in American communities. CBP data indicates overall drug seizures at the U.S.-Mexico border and our maritime borders, by pounds seized, are trending down. However, there is a key exception: seizures of lighter and more potent illicit fentanyl are increasing at a fast pace.

Illicit fentanyl, more potent than heroin or morphine, can be cheaply produced and smuggled in small quantities. Data shows that most illicit fentanyl is smuggled into the U.S. through the southern border and, specifically, through Ports of Entry (POEs) and by U.S. citizens. Maritime borders are also susceptible to fentanyl smuggling. To stop the flow of illicit fentanyl into America, it is important to focus on policies and programs that understand how fentanyl is being smuggled into the U.S. and by whom. There is also a need to address demand, since focusing on supply itself is unlikely to solve the challenge.

[1] CBP AMO data indicates nearly 37,000 pounds of the total – out of the 304,400 pounds of illicit drug substances – were seized at the southern border. Most of that amount (33,000 pounds or about 90 percent) were seized at non-land ports, which indicates that they likely were seized at southern maritime and air environments.

[2] This is significantly down from FY 2021 (813,000 pounds), which includes an outlier month where 445,000 pounds of illicit drug substances were seized.

[3] CBP seized two and a half tons of fentanyl precursors at the Laredo Port of Entry on September 9, 2023. These precursors were making their way down to Mexico.

[4] The provision establishing the Commission was included in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year (FY) 2020.

The National Immigration Forum would like to thank Jordan Ennis, Policy and Advocacy Intern, for contributing to the development of this paper.