Who is an asylee?

A person, who sought and obtained protection from persecution from inside the United States or at the border. An asylee is an individual who meets the international definition of refugee – a person with well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group, who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence. In the U.S., asylum seekers apply for protection from inside the country or at a port of entry.

In contrast, a refugee is a person who applies for protection from outside of the U.S.

Who is an unaccompanied alien child (UAC)?

A minor immigrant child who arrived in the U.S. or at a port of entry without a parent or guardian. UACs are children below the age of 18, who enter the U.S. without their parents or legal guardians. Those who arrive with a parent or legal guardian will be designated as UACs if the government pursues criminal charges against their parents or legal guardians. After apprehension by immigration authorities, UACs are placed in temporary care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which screens them to determine whether they have been victims of trafficking and ensures timely appointment of legal pro bono counsel for as many of the children as possible.

When a family member or other sponsor in the United States is available to take custody of a UAC and provide care, ORR places the minor with that family member or other sponsor. When a family member or other sponsor is not available, ORR places the UAC into a foster home. ORR is required to ensure that the actions and decisions related to care and custody of UACs are in the child’s best interest.

How can an individual apply for asylum in the U.S.?

Either affirmatively or defensively. Depending on whether the applicant is or isn’t in removal proceedings, he or she may apply for asylum either through the affirmative asylum process or the defensive asylum process. Under both processes, asylum seekers must indicate a “well-founded fear” of persecution in their home countries during a credible fear interview with immigration authorities. Otherwise, they are ordered for removal.

- Affirmative asylum process – Individuals can apply for asylum affirmatively if they are physically present in the U.S., regardless of how they entered the country within one year after arrival. They can also apply for asylum at ports of entry. In an affirmative asylum process, a USCIS officer decides whether the individual will be granted asylum in the U.S. If USCIS denies an asylum application in the affirmative asylum process after the individual’s visa has expired, he or she is referred for removal but can utilize the defensive asylum process to renew his or her request for asylum.

- Defensive asylum process – Individuals can seek asylum as a defense against removal after they are apprehended by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) or Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents in the U.S. or at one of the ports of entry without valid visa. A person in the defensive asylum process requests asylum in immigration court where an immigration judge decides whether or not the applicant will be granted asylum.

Individuals seeking asylum at ports of entry are placed in expedited removal proceedings by CBP and referred for a credible fear screening interview conducted by an asylum officer. The credible fear interview provides the applicant with the opportunity to explain how he or she has been persecuted or has a well-founded fear of persecution based on his or her race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion if returned to his or her country. Based on the interview, the officer then decides whether the applicant has a “significant possibility” of being eligible for asylum. If so, the officer refers such individual to immigration court in a defensive asylum application process. If not, the applicant is ordered removed and may seek review by an immigration judge in effort to appeal the negative decision.

How long does the asylum process take?

The length of the asylum process varies, but it typically takes between 6 months and several years. The length of asylum process may vary depending on whether the asylum seeker filed affirmatively or defensively and on the particular facts of his or her asylum claim.

Under the affirmative asylum process, the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) requires USCIS to schedule the initial interview within 45 days after the application is filed and make a decision within 180 days after the application date.

Under the defensive asylum process, applicants must go through the immigration court system, which faces significant backlogs. As of July 2018, there were over 733,000 pending immigration cases and the average wait time for an immigration hearing was 721 days. The backlog has been worsening over the past decade as the funding for immigration judges has failed to keep pace with an increasing case load.

Are asylum seekers released before their immigration court hearings?

It depends. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) requires all individuals seeking asylum at ports of entry to be detained. They remain in detention even after officials confirm their claims as credible, unless the officials decide the applicants are unlikely to flee and do not pose a safety threat. In addition, they must pay a bail, which they often cannot afford. If released, many asylum seekers are monitored by GPS ankle bracelets. Data show that 96 percent of asylum applicants show up to all their immigration court hearings.

If officials determine the applicants’ claims are not credible, the asylum seekers are ordered for “expedited removal” and do not receive an immigration court hearing.

Under prior administrations, immigration authorities regularly released migrants from custody while their cases were pending in the immigration court system. Those migrants were still required to check in with immigration authorities and attend hearings in immigration court. The Trump administration has modified these policies to release as few asylum seekers as possible. A recent federal court decision requiring case-by-case determinations as to whether asylum seekers pose a flight risk or threat to public safety is likely to lead to more releases pending their hearings.

Does the government provide defensive asylum seekers with appointed immigration lawyers?

No. Asylum seekers may hire their own attorney if they can afford to do so, but are not provided an attorney by the government, as criminal defendants are. Some attorneys offer pro bono services to asylum seekers and UACs in immigration proceedings.

Chances of obtaining asylum are statistically five times higher if the applicant has an attorney. In FY 2017, 90 percent of applicants without an attorney were denied, while almost half of those with representation were successful in receiving asylum.

How many people are granted asylum?

Nearly 20,500 individuals in FY 2016. In fiscal year (FY) 2016, the most recent year for which data are available, 20,455 individuals were granted asylum, which is about 28 percent out of the 73,081 cases. Approval rates varied by immigration court from about 10 percent to 80 percent.

USCIS approved 11,729 affirmative asylum applications in FY 2016, representing slightly more than 10 percent out of the 115,399 affirmative asylum applications filed with the agency. This represented a 34 percent decline from the 17,787 affirmative asylum applications granted in FY 2015. The decrease occurred as the administration transferred a large number of USCIS asylum officers from the affirmative interview process to conduct credible and reasonable fear screening interviews. Even with increased overall staffing within the USCIS Asylum Division, the number of affirmative applications granted declined considerably and the number of applications climbed to a 12-year high of almost 200,000, as fewer asylum officers were assigned to review affirmative applications.

In FY 2016, 8,726 individuals were granted asylum defensively by an immigration judge or the Board of Immigration Appeals, an increase of 7 percent over the 8,246 defensive asylum grants in FY 2015.

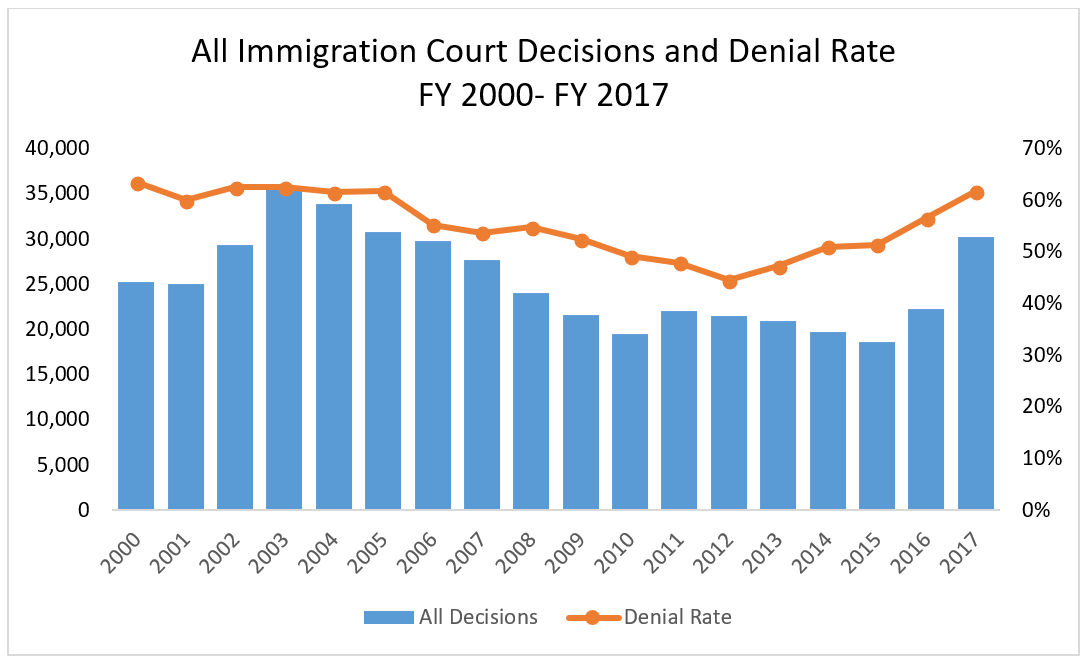

In FY 2017, as instability in Central America’s Northern Triangle showed few signs of ending, immigration judges decided over 30,000 asylum cases, a considerable increase over the roughly 22,300 asylum cases decided in FY 2016, and the most FY 2005.

However, the denial rate grew along with number of asylum cases, climbing to 61.8 percent in FY 2017, up from 56.5 percent in FY 2016. Five years earlier, the denial rate stood at 44.5 percent.

Source: http://trac.syr.edu/immigration/reports/491/

Where do asylees resettling in the U.S. come from?

Mostly from China followed by the Northern Triangle countries. Nearly 22 percent of individuals who were granted asylum affirmatively or defensively in FY 2016 came from China, followed by El Salvador (10.5 percent), Guatemala (9.5 percent), Honduras (7.4 percent) and Mexico (4.5 percent). While most applicants seeking asylum through the defensive process were originally from China (37.9 percent) in FY 2016, the largest number of asylum seekers in the affirmative process came from El Salvador (11.9 percent), China (11.7 percent) and Guatemala (11.2 percent).

Where do asylees live in the U.S.?

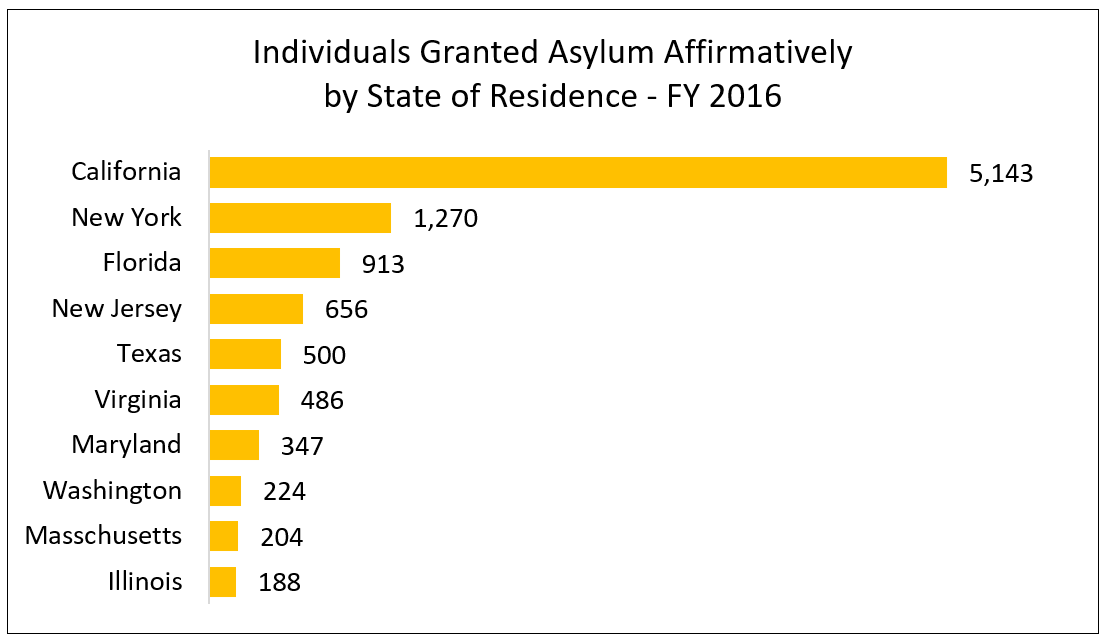

Throughout the United States, with the largest number in California. The largest number of individuals granted asylum in the affirmative process lived in California in FY 2016 (43.8 percent), followed by New York (10.8 percent) and Florida (7.8 percent).

Source: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Refugees_Asylees_2016_0.pdf

Source: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Refugees_Asylees_2016_0.pdf

Can asylees legally work in the United States?

Yes. Once granted asylum, an asylee is authorized to work in the U.S. and apply for a social security number. Asylum seekers are also eligible for work authorization if their case has been pending for more six months.

Can an asylee become an U.S. citizen?

Yes. One year after receiving asylum in the U.S., the asylee may apply to be a lawful permanent resident, or a green-card holder. To receive a green card, the asylee must have been physically present in the U.S. for at least one year after receiving asylum, and at the time of filing his or her green card application, continue to meet the definition of a refugee, continue to be admissible to the U.S. for permanent residence, and not be resettled in another foreign country. If approved, he or she must wait at least four years before applying for citizenship.