What Is Operation Streamline?

Operation Streamline is a program under which federal criminal charges are brought against individuals apprehended crossing the border illegally. Created in 2005 as a joint initiative of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ), the program fast-tracks resolution of these immigration offenses, providing for mass proceedings in which as many as 80 unlawful border crossers are tried together in a single hearing, typically pleading guilty en masse.

Under federal law, those caught making a first illegal entry may be prosecuted for a misdemeanor (under 8 U.S.C. § 1325) punishable by up to six months in prison, and those who reenter after deportation may be prosecuted for a felony (under 8 U.S.C. § 1326) punishable by up to 20 years in prison. Operation Streamline is a fast-track program: Migrants apprehended pursuant to it are targeted for accelerated prosecution for illegal entry or illegal re-entry.[1] Several steps of a federal criminal case with prison and deportation consequences – including initial appearances, preliminary hearings, pleas, and sentencing – are combined into a single hearing that may last only minutes.[2] The average prison sentence for unlawful entrants typically varies between 30 and 180 days, depending on whether the individual has a criminal record in the U.S. or has prior reentry convictions.[3]

Before Operation Streamline, agents with CBP’s Border Patrol agency routinely returned first-time undocumented border crossers to their home countries or referred them to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) (or the Immigration and Naturalization Service, ICE’s predecessor agency) to face removal charges in the civil immigration system. Typically, U.S. attorney’s offices, which are part of DOJ, prosecuted only those migrants with criminal records or those who made repeated attempts to unlawfully cross the border.[4] Facing growing unlawful migration across the U.S.-Mexico border, DHS and DOJ announced Operation Streamline in 2005 as an effort to ramp up immigration enforcement to deter illegal border crossings, using a streamlined criminal process to punish unlawful entry.[5]

What Are the Concerns with Operation Streamline?

Several key concerns have arisen since the implementation of Operation Streamline. Critics argue the high cost of the program diverts scarce resources from core law enforcement priorities, community safety, and the courts.

1. Misallocation of Resources

Critics argue that Operation Streamline leads to a misallocation of funding by shifting prosecutorial resources away from significant threats to public safety. Rather than spending additional time and resources prosecuting serious crimes, including gun and drug trafficking or organized criminal activity, federal lawyers and courts are spending disproportionate time and resources on illegal entry or re-entry cases.[6]

As immigration prosecution rates have risen in federal courts, prosecution of other criminal matters has declined. By 2018, a majority of all federal criminal prosecutions –approximately 61% – were immigration-related, followed by drug-related offenses.[7] While immigration prosecution increases routinely drove monthly increases in federal criminal prosecutions, drug possession and other serious criminal prosecutions steadily have declined.[8]

2. Increased Criminalization and Financial Costs

Since 2005, Operation Streamline has dramatically increased the caseloads in the federal courts. This volume of prosecutions creates a burden on the federal judicial system, especially in southwestern districts – just five of the country’s 94 federal districts (Southern California, New Mexico, Arizona, West Texas and South Texas) handle 78% of all immigration-related criminal cases filed in federal district courts nationwide.[9] These five districts are among the top-six busiest federal district courts in the country.

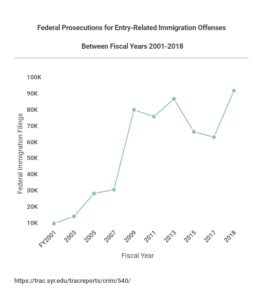

The expansion of Operation Streamline reflects an increasing emphasis over the last two decades on handling immigration offenses through the criminal justice system. Individuals criminally prosecuted for entry-related offenses increased nearly 500%, rising from 15,392 cases in FY 1997 to 90,067 cases in FY 2013.[10] While immigration prosecutions declined between FY 2013 until FY 2017, they have spiked again in recent years, climbing to approximately 100,000 prosecutions in FY 2018.[11]

The criminalization of immigration offenses, including those handled through Operation Streamline, strains U.S. courts and prisons, particularly along the southern border. While Operation Streamline comprises only a portion of the costs of criminalization, those costs – including incarceration expenses, operating expenses for the courts, and the price of prosecution and defense attorneys – are not insubstantial. In the first ten years of Operation Streamline (FY 2005 to FY 2015), incarceration costs related to the program were estimated to be more than $7 billion.[12]

3. Undermining Due Process

Without a meaningful opportunity to present their individual claims for asylum and other forms of relief under Operation Streamline, immigrants’ due process rights are under threat. Facing pressure to move migrants through the criminal justice system quickly under the program, federal courts in the border regions have resorted to holding hearings and sentencing en masse. In these hearings, federal judges address up to 80 defendants at a time, going through the colloquy for a guilty plea with dozens of defendants at once.[13] These mass proceedings lack important safeguards and individualized adjudication necessary to afford due process to impacted migrants. Individual defendants in these hearings may have met with a defense attorney for less than 20 minutes, and their guilty pleas with potential prison and deportation consequences are resolved in a hearing that may last only minutes.[14] Critics have characterized this as a “due process disaster”[15] or “assembly-line justice.”[16]

While sidestepping standard federal criminal procedures allows federal prosecutors and judges to move substantial numbers of immigration defendants through the court system and provides some efficiency gains, it does so at the cost of undermining basic due process protections. Such practices raise serious concerns about the potential miscarriage of justice.

Recommendations for Improvement

- Prosecutorial resources should focus on significant threats to public safety, not immigration offenses. Enforcement resources should be directed at prosecuting threats to community safety, including gun and drug trafficking and organized criminal activity. Operation Streamline’s focus on non-violent immigration offenses misallocates limited federal resources, forcing courts to spend disproportionate time and resources on illegal entry or re-entry cases.

- Immigration offenses should be primarily addressed through the civil immigration system. Rather than addressing immigration offenses through the criminal justice system, the federal government should return to the pre-Operation Streamline practice of primarily relying on the civil immigration system. Shifting away from Operation Streamline’s focus on criminal enforcement will reduce costs to taxpayers, including those relating to criminal detention, and preserve limited prosecutorial and judicial resources. Such an approach is consistent with public safety and would not prevent federal prosecutors from initiating illegal entry prosecutions in individual cases in which prosecutors believe such charges are appropriate.

- Federal policies should reinforce due process in the federal courts, not undermine it. The utilization of mass proceedings in conjunction with Operation Streamline threatens important rights. To the extent certain immigration offenses need to be resolved in the criminal justice system, hearings and sentencing should not be handled en masse. Criminal defendants must receive due process, including access to counsel and individualized hearings.

* * *

[1] Eleanor Acer, “Criminal Prosecutions and Illegal Entry: A Deeper Dive,” Just Security, July 18, 2019, available at https://www.justsecurity.org/64963/criminal-prosecutions-and-illegal-entry-a-deeper-dive/.

[2] Id.

[3] Bryan Schatz, “A Day in the “Assembly-Line” Court That Prosecutes 70 Border Crossers in 2 Hours,” Mother Jones, July 21, 2017, available at https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2017/07/a-day-in-the-assembly-line-court-that-sentences-46-border-crossers-in-2-hours/.

[4] Joanna Lydgate, “Assembly-Line Justice: A Review of Operation Streamline,” Chief Justice Earl Warren Institute on Race, Ethnicity & Diversity, UC Berkeley Law School, Jan. 2010, available at http://www.law.berkeley.edu/files/Operation_Streamline_Policy_Brief.pdf, at 1.

[5] U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Performance and Accountability Report: Fiscal Year 2009, download available at https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=691162, at 12-13.

[6] See Acer, “Criminal Prosecutions and Illegal Entry: A Deeper Dive”; Lydgate, “Assembly-Line Justice: A Review of Operation Streamline,” at 9.

[7] TRAC, “Federal Prosecution Levels Remain at Historic Highs,” Syracuse Univ., December 12, 2018, available at https://trac.syr.edu/tracreports/crim/540/.

[8] Id.

[9] Administrative Office of the United States Courts, “U.S. District Court – Judicial Business 2018,” 2018, available at https://www.uscourts.gov/statistics-reports/us-district-courts-judicial-business-2018.

[10] Marc R. Rosenblum, et al., “The Deportation Dilemma: Reconciling Tough and Humane Enforcement,” Migration Policy Institute, April 2014, download available at https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/RemovalsOverview-WEBFINAL.pdf, at 28-29.

[11] TRAC, “Federal Prosecution Levels Remain at Historic Highs” (“Approximately 61 percent of all [165,070] federal criminal prosecutions in FY 2018 were immigration-related”).

[12] John Burnett, “The Last ‘Zero Tolerance’ Border Policy Didn’t Work,” NPR, June 19, 2018, available at https://www.npr.org/2018/06/19/621578860/how-prior-zero-tolerance-policies-at-the-border-worked.

[13] Lydgate, “Assembly-Line Justice: A Review of Operation Streamline,” at 13.

[14] Acer, “Criminal Prosecutions and Illegal Entry: A Deeper Dive.”

[15] Id.

[16] Lydgate, “Assembly-Line Justice: A Review of Operation Streamline.”