A PDF version of this resource is available here.

As of June 24, 2025, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was holding the highest recorded number of individuals in immigration detention in U.S. history. At more than 59,000 individuals, the population was 140% over the federally funded capacity for 41,500 beds. Data shows that 47% of individuals in immigration detention at that time did not have a criminal record, nor did they have pending criminal charges, and less than 30% had been convicted of crimes. Between January 1 and June 24, ICE deported around 70,000 people with criminal convictions, but many of the documented infractions were for immigration or traffic offenses. This is a departure from the Trump administration’s promise to prioritize detaining and deporting immigrants with criminal records or those who are public safety threats.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBA) (H.R. 1), signed into law by President Trump on July 4, provides an additional $45 billion over four years to increase immigration detention capacity, including family detention facilities. This funding — an extra $10.6 billion per year — will allow ICE to increase detention capacity to at least 116,000 beds, over 2.5 times the current numbers. Moreover, because ICE is limiting its discretion to release individuals from immigration detention on bond during removal proceedings, except in a small handful of narrow circumstances, the immigration detention population in the U.S. will continue to grow.

Overview: Immigration Removal Proceedings Process

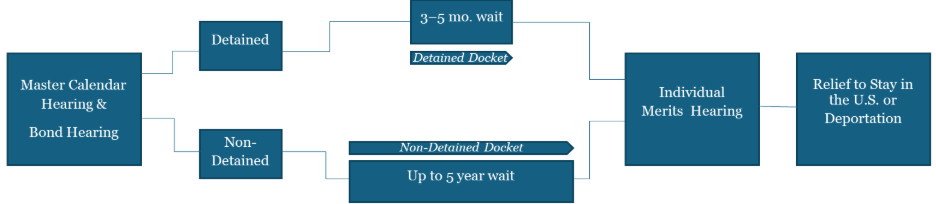

Removal proceedings begin with a master calendar hearing after an individual is issued a Notice to Appear (NTA). Individuals held in detention can typically request a bond hearing to be released, but access has recently been reduced. Following either the master calendar hearing or bond hearing, individuals generally have an individual merits hearing. The wait time for an individual merits hearing depends on whether the individual is in detention or not, with the detention docket historically moving much faster.

Master Calendar Hearings

A Master Calendar Hearing (MCH) before an immigration judge is an individual’s first court hearing in the removal proceedings process. The immigration judge reviews the charges against the individual, such as that they are in the country unlawfully or overstayed a visa. The purpose of an MCH is to inform individuals of their legal rights and access to legal services, advise them of the evidence they can present in court, and to generally give more information about the process. If the individual believes that the charges are incorrect, they can deny them and ask the government to prove its case.

After this review, an individual states their claim for relief. They are then given the opportunity to file an application to stay in the U.S. which they will bring back to court. Finally, the immigration judge will set important dates for an individual’s case, including deadlines to submit relevant applications, a date for another MCH if necessary, and a date for an individual’s merits hearing. Bond hearings to be released from immigration detention can be scheduled before or during an MCH.

Because an individual does not present any evidence during an MCH and their claim for relief is not evaluated until their individual merits hearing, individuals are rarely ordered removed during an MCH. Thus, unless the individual did not appear at the MCH, resulting in a in absentia removal, deportation following an MCH is unlikely. Data shows individuals routinely appear for these hearings, with only eight percent of individuals in deportation proceedings receiving in absentia removal orders over the past three years. Moreover, in that same period, data indicates that for individuals who are represented by counsel, only three percent received in absentia removal orders.

Bond Hearings

The main avenue for individuals to leave an immigration detention facility during the first six months of the second Trump administration was through an immigration bond hearing. This differs from previous administrations, in which ICE exercised its discretion to release at least some individuals who are not considered public safety threats from detention while their immigration court cases proceeded. Individuals must actively request a bond hearing because they are not offered one. In bond hearings, immigration judges determine whether someone is eligible for a bond or redetermine the bond amount set by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Upon payment of a bond, they are released from immigration detention. Individuals must actively request a bond hearing because they are not offered one.

Those who left the U.S. either voluntarily or involuntarily, were issued a removal order at the border, committed aggravated felonies, were denied and did not appeal for relief from removal by an immigration judge, or were denied relief from removal by the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) after an appeal are ineligible for bond. For eligible individuals, if the immigration judge determines that the individual does not pose a danger to property or other people, is not a national security risk, and is likely to show up for further immigration proceedings, the immigration judge grants a bond, and the individual is released.

Recently, immigration bond hearings enabled two young Dreamers to be released from detention centers. Ximena Arias Cristobal, a Georgia teen who was taken into ICE custody after a traffic stop, was granted a bond and released after an immigration judge determined that she was not a flight risk or a danger to the community. Similarly, Caroline Dias Goncalves, a college student and recipient of TheDream.US scholarship, was arrested by ICE after information from a traffic violation was shared in a non-immigration dedicated messaging group between local, state, and federal law enforcement. She requested and was granted a bond as well, allowing her to be released from detention.

Detained v. Non-Detained Dockets

If individuals are not granted bond or are ineligible for bond, they are held in detention, and their case is placed in the detained docket. If individuals are granted a bond, they are released, and their case is placed in the non-detained docket. Both detained and non-detained individuals must wait for their individual merits hearing. Detained dockets have historically moved much faster than non-detained dockets, as immigration courts will schedule hearings for detained individuals as soon as possible, and hearings are typically set a few weeks or months out. In contrast, non-detained dockets can take years.

Individual Merits Hearing

During individual merits hearings, immigrants present their case to remain in the U.S. This can include a case for asylum, withholding of removal, cancellation of removal without a green card, adjustment of status, or deferred action. Immigration judges then issue a final decision on whether the individual will be allowed to remain in the U.S. As of June 2025, immigration judges issued removal and voluntary departure orders in 50.5% of cases that reached the individual merits hearing stage. If neither party appeals the decision, the immigration judge’s decision becomes final.

New Limitations on Bond Hearings Expanding Mandatory Detention

Following the release of a July 8 memo, bond hearings to be released from detention may no longer be accessible for many undocumented immigrants. In the memo, ICE’s acting director Todd Lyons, instructs officers to detain immigrants for “for the duration of their removal proceedings.” Lyon’s memo asserts that the federal government has “revisited its legal position on detention and release authorities” and reinterpreted an immigration law from the 1990s, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), such that mandatory detention applies to all “arriving aliens.” This means that all individuals who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border between ports of entry can be detained, not just those who arrived recently, as had been the practice under prior administrations. The memo states that immigrants may be released on parole in rare instances, but this will be at the discretion of an immigration officer and not an immigration judge.

The American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA) reports that immigration judges are now routinely rejecting individuals’ requests to be released from detention, which it argues deprives individuals of their statutory right to have an immigration judge review whether their detention is in fact necessary. Other courts continue to grant bonds, but ICE has appealed those decisions in some cases and the Supreme Court has declined to intervene. In March 2025, a Washington immigration court faced litigation challenging a similar policy that denied bond hearings to longtime U.S. residents.

Many observers contend this policy change will likely lead to immigrants being detained indefinitely, expanding mandatory detention beyond those who have committed serious crimes to include those who pose no threat to public safety. It is also likely that detained docket wait times for an individual merits hearing will increase due to the sudden surge of noncriminal immigrants in detention, resulting in an increased backlog. This policy of mandatory detention will deny millions of long-term U.S. residents — individuals who have built their lives, raised families, and contributed to their communities — substantive review of their individual circumstances. Others caution that eliminating bond hearings risks turning the immigration system into “a tool of mass control, unchecked by law or logic.”

ICE officials assert that the policy allows for everyone who entered the U.S. without authorization to be treated equally, and, with increased funding from the OBBA, it now has the capacity to detain more immigrants for extended periods of time, making release unnecessary. Nonetheless, in the memo itself, the administration acknowledges the policy is likely to face legal challenges.

The National Immigration Forum would like to thank Reine Choy, Policy & Advocacy Intern, for her work developing this explainer.