I. Introduction

Immigrants working in the childcare sector play an outsized role in addressing workforce challenges as a whole. Because so many members of the workforce are dependent upon childcare, shortages of childcare workers have cascading effects across the economy. Immigrants already make up approximately 20 percent of the childcare workforce and provide a double-edged benefit of sorts – filling needed gaps in the childcare sector while also boosting labor force participation rates in other sectors of the economy. In short, immigrant workers address the ongoing demand for childcare workers, while also making it possible for others to fill jobs in different sectors because they make it easier to obtain childcare.

The focus of this explainer is to provide background on the U.S. childcare sector, highlight immigrant workers’ roles in the sector, and demonstrate how these workers benefit workers in other sectors of the economy.

II. Notable Developments in Federal Childcare Policy

Going back to the 1960s, childcare begin to receive increasing federal attention, notably in 1965 with the introduction of the “Head Start” program which was part of President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” which provided access to preschool and childcare to low-income families with young children. Soon thereafter, another notable effort at a national system for child development and childcare, the proposed “Comprehensive Child Development Act,” failed in 1971, after President Richard Nixon vetoed it despite passing both the House and the Senate with bipartisan support.

Another major federal childcare program was not enacted until the passage of the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 1990 (CCDBG) during the George H.W. Bush administration. CCDBG assisted both low and middle-income families. CCDBG established funding that was made available to the states to help subsidize childcare for families that met the eligibility requirements, and the funding was based on a sliding scale. It also improved the quality and availability of childcare.

Since the 1960s, American families increasingly have sought additional childcare options outside the home. From 1980 to 2000, the number of children living in single-parent families grew from 21 percent to 31 percent, increasing the demand for childcare workers. It was, however, not just single parent households that struggled with childcare but also two-parent households, particularly those in which both parents were working. Between 1970-2015, the number of households with both parents working had grown from 31% to 46%. In 2024, the percentage of married-couple families with both parents working was 49.6%.

Childcare and COVID-19

In recent decades, the childcare workforce grew steadily, at least until the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the childcare workforce experienced a dramatic drop during the pandemic, as illustrated in the chart below. It did not fully recover to pre-COVID levels until July 2023. Having largely returned to its pre-pandemic growth path, the childcare sector is projected to grow at least through 2030, in terms of there being an increasing demand for childcare services.

Trend Line And Deficit of All Child Care Employees Pre-Pandemic Vs. Post-Pandemic

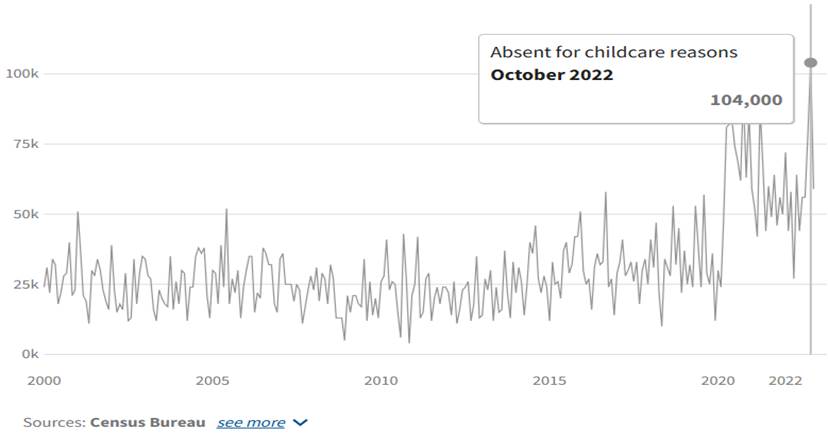

Another way to view the impacts of COVID-19 on the childcare sector is to look at the number of people missing work just for childcare reasons. Pre-COVID, the highest number of employees who cited childcare as the primary reason for work absences was 58,000 in September 2016. That number increased significantly at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, reaching 81,000 in April 2020 and hitting an all-time high of 104,000 people absent from work in October 2022.

Number of People Absent From Work For Childcare Reasons

U.S. Childcare Profile

Women make up a much larger proportion of the childcare workforce than men – about 89%. The childcare workforce is highly diverse – only a slight majority (about 56%) are non-Hispanic whites, as compared to the general population, which is 76% non-Hispanic whites. Immigrants make up close to 20% of the childcare workforce.

Daycare is often divided into two types, 1) center-based care (daycare centers and schools) and 2) home-based care. In a 2019 study, it was found that 59% of children five or younger had at least one weekly childcare provider that was not a parent. Of those receiving childcare, 62% received that care at a center of some kind, and the rest were cared for by either a non-parent relative or a non-relative. In 2022, the majority (61.5%) of childcare workers worked for a childcare center, 19.7% for elementary and secondary schools, and 18.8% for private households. In 2023, about 23% of childcare workers were self-employed.

Even before COVID-19, researchers identified areas lacking childcare opportunities, deeming them “childcare deserts.” A “childcare desert” is officially defined as “any census tract with more than 50 children under the age of 5 that contains either no child care providers or so few options that there are more than three times as many children as licensed child care slots.” Subject to detailed analysis using mapping tools, childcare deserts are not restricted to rural areas. In fact, the data shows that more people in suburban areas are impacted by childcare shortages than in either rural or urban areas. Researchers have also shown disparities by race, with 57% of Latinos having access to childcare, 50% of whites having access, and only 44% of African Americans. Under this criteria, childcare access simply means the availability of any childcare provider.

Compensation levels represent a barrier discouraging many potential childcare workers from entering the sector. The median wage for a childcare worker in 2024 was $32,050 per year or about $15.41 an hour, usually with few (or no) benefits.

Over time, increasing numbers of U.S. adults have obtained bachelor’s degrees, opening up more lucrative opportunities in other sectors of the economy. Accordingly, these native-born workers have increasingly drifted away from childcare occupations over time. Accordingly, immigrant contributions to the childcare workforce are likely to become increasingly important.

Women and Childcare

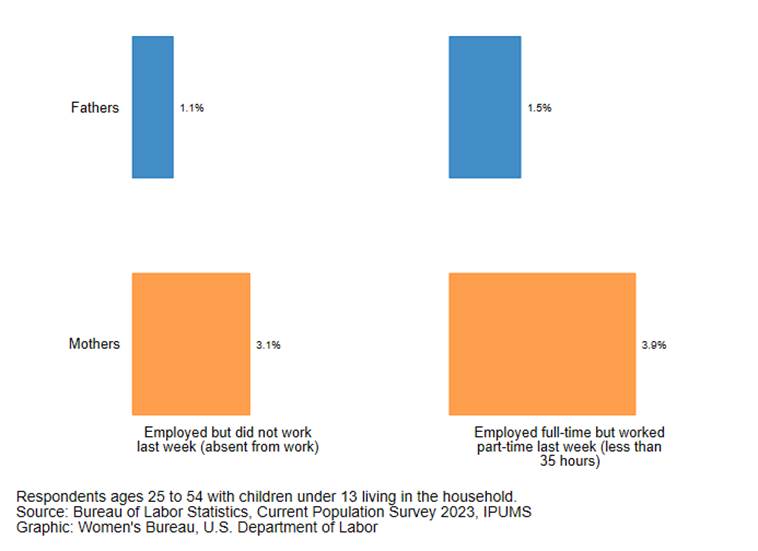

Childcare workers help boost labor force participation rates, allowing individuals who otherwise would be forced to stay at home to enter the labor force. Studies have shown that this disproportionately impacts women and their availability to enter into the workforce.

Father vs. Mother Comparison: Absent From Work For Childcare Reasons

Women in particular face barriers to their participation in the labor force, with childcare as a central issue. Increasing access to childcare for women, particularly those with young children that have not yet entered kindergarten, would increase women’s participation rates in the workforce, with benefits to employers and the economy as a whole. Filling childcare workforce gaps is a prerequisite to achieving this goal.

This discussion of the benefits of women entering the workforce in no way seeks to criticize the choices of many mothers to stay at home to care for their children (or, similarly, of fathers who choose to stay home). Childcare, whether voluntary or paid, is work and is a worthy occupation benefiting families, society, and the economy. But ensuring that the childcare workforce is sufficient to meet the needs of parents – mothers and fathers alike – provides additional opportunities to workers of all backgrounds. Immigrant workers are an essential part of this solution, filling needed workforce gaps and providing benefits to families, employers, other workers, and the economy at large.

Au Pairs, Nannies, and Babysitters

Any discussion about the childcare sector would not be complete without describing the differences between au pairs, nannies, and babysitters, each of which are discrete childcare worker categories.

An au pair is defined as having been admitted to the U.S. through a J-1 visa and stays with a family to provide childcare for one year with the option to extend their visa for another year. The program is more than just a childcare program, as there is a cultural exchange and educational component to the program.

A nanny is someone who provides parents with on-going care for the mental and physical development of the children, usually within the family home for months or years and is often full time. It is estimated that about 14.7% of nannies are foreign-born non-citizens and another 12% are foreign-born U.S. citizens. Foreign-born nannies can come in under the H-2B visa program or the much longer EB-3 employment based visa process. In addition, a smaller segment of nannies may enter under the B-1 visa for domestic help. These workers enter the U.S. with U.S. citizens or LPRs for a temporary stay of specified duration. The B-1 is a broadly used business visa, so it is difficult to determine how many of them are used for the express purpose of an accompanying nanny.

It is also the case that some nannies have a degree in childhood development or early childhood education given their job responsibilities. About 85% of nannies have some college education and 46% of those with college degrees major in a field related to children.

A babysitter is someone who provides temporary or occasional care addressing the safety and basic necessities of children. This care can be provided on an as-needed-basis or be scheduled on a regular basis such as after school each day. Most babysitters are paid cash on an hourly basis.

According to data from the U.S. State Department, about 20,000 au pairs come into the U.S. each year, representing only a small percentage of the overall childcare sector. There is a much larger number of nannies – approximately 550,000 – providing childcare. The nanny population includes a mix of native-born, naturalized citizen, and non-citizen workers, with each nanny working for an average of 1.5 families due to nanny-share arrangements. Some places have a higher concentration of nannies than others, with New York City having the most – an estimated 14,000 nannies.

III. Immigrants in the Childcare Sector

Immigrants currently represent one-in-five of all the childcare workers, a number that approaches one-in-two in large urban areas.

Even as the increasing education levels of the native-born make them less likely to enter the childcare sector, it is worth noting that immigrants within the sector are higher-educated than native-born workers in the sector, often having college degrees. There are many reasons for this disparity, including credential and licensing barriers that serve as a barrier against some educated immigrant workers securing work in “higher-skilled” U.S. occupations. Immigrants often have to start all over to meet the academic requirements in an occupation or take jobs in areas other than those of their academic study, including childcare.

Immigration Enforcement and Childcare

Past history has shown that the immigrant population within the childcare sector are particularly at risk of disruption due to the immigration enforcement activities of their local communities or the federal government.

In addition to leading to increased deportations, increased levels of interior immigration enforcement discourage some non-citizen childcare workers from going to work, or otherwise going out into the community, impacting working family members who may suddenly find themselves without childcare. It is estimated that about 6.7% of childcare workers are undocumented. While this is a relatively small percent of the overall childcare workforce, the chilling effect on the larger immigrant workforce can create additional disruptions in this sector. As the second Trump administration ramps up interior immigration enforcement in the first half of 2025, it is still too early to get much specific data on the impacts of these activities on the workforce as a whole, including the childcare workforce. But historically, prior high-profile interior immigration enforcement activities created confusion and fear among the immigrant community, reduced total working hours, and increased costs for services. If these historic impacts repeat themselves, it is highly likely the current immigration actions will depress the availability of childcare workers, significantly in some areas.

This chilling effect is especially true for childcare workers working in center-based settings as compared with those working in private settings such as households. That is because center-based childcare providers are more likely to encounter state and federal agencies, which conduct regular oversight and inspection of these facilities. Center-based childcare employees’ personal information is also more readily made available to government authorities for immigration verification, tax, or accreditation and licensing purposes. Accordingly, it is more likely that immigration enforcement activities would target childcare centers than individual homes, creating more vulnerabilities for these center-based immigrant workers.

IV. Labor Force Participation Rates And Childcare

Childcare is a uniquely important sector of the economy because it frees up other workers to engage in work in other sectors. As women have entered the workforce in large numbers over the past several decades, childcare has become increasingly important in unlocking workers who otherwise would be forced to remain at home to care for their own children. Viewed in this way, the childcare workforce, notably immigrant workers filling needed gaps in that workforce, play an increasingly important role in the U.S. economy, yielding benefits to many other business sectors.

Researchers have shown a direct relationship between labor force participation rates and the availability of childcare. In particular, studies have found that the supply of immigrant childcare workers increases the labor force participation rates of women with young children. The challenges faced by workers forced to stay home to provide childcare drew elevated attention during COVID-19, contributing to the so-called “great resignation” that led many workers to leave the workforce during the pandemic. In 2021, in the midst of COVID-19, 46 percent of women facing extended terms of unemployment, left the workforce due to childcare issues. Due in part to the stabilization of the childcare workforce after the peak of the pandemic, by 2024 women’s employment rates generally returned to pre-COVID-19 rates or higher.

V. Conclusion

The important role childcare plays in a nation’s economic well-being is often overlooked and undervalued; nevertheless, it can play a significant role across all businesses in that it is a multiplier in labor force participation rates. Immigrants already play a critical role in childcare – one out of every five childcare workers is an immigrant. Immigrant childcare workers are valuable contributors to this sector, creating additional opportunities for parents – especially women – to enter the workforce, increasing labor force participation rates and promoting economic growth.