Introduction

The fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban in August 2021 has prompted a refugee crisis. UNHCR reports that more than 550,000 Afghans have been displaced since January due to Taliban advances. Those most at risk include women leaders and activists, human rights workers, journalists, and tens of thousands of individuals who have assisted U.S. efforts in the country and are marked by their connection to the U.S. military. In the capital of Kabul, the Taliban is reportedly going door-to-door, targeting those with close ties to the U.S.

Initially, it appeared that potentially hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees who had assisted the U.S. military effort would be eligible to come to the U.S. under either the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) program or a broader Priority-2 (P2) refugee status that was announced on August 2. However, both processes take years to complete and — in the case of P2 status — they required individuals to escape on their own to a third country before applying. In addition, neither status was available to many of the Afghans who are most at most risk, including Afghan women and girls, human rights workers, and journalists.

Due to the inadequacy of the SIV and P-2 programs in the context of an emergency evacuation, on August 23 the administration announced it would be using its humanitarian parole authority to process in evacuated Afghans who do not already have visas. This explainer will define humanitarian parole and describe how it is being used in the ongoing evacuation. It will discuss the eligibility and vetting protocols that have been put in place to secure the process and explain the benefits (or lack thereof) that parolees receive when they arrive in the United States.

What is parole in the context of U.S. immigration law?

Under the Immigration and Nationality Act, parole is a tool that allows certain individuals to enter and stay in the U.S. without a visa. Parole is granted either for “urgent humanitarian reasons” or because the entrance of an individual is determined to be a “significant public benefit” to the U.S. While visa processes can take years or decades, the parole process may take days or even just hours to complete. While it is often used when rapid admissions are necessary, each parole application must be considered individually and receive sign off from senior government officials. Parole programs all involve various vetting and processing requirements (discussed below).

There are several different categories of parole, and the authority has been used for a wide range of populations over the years. Parole has been used for international entrepreneurs under the IEPP and arriving Cubans under wet foot dry foot; it has been used for noncitizen veterans hoping to remain in the U.S. and for DACA recipients hoping to travel outside the country.

Parole has also been used — repeatedly and to great effect — to facilitate the evacuations of allies and others at risk following the withdrawal of U.S. troops from war-torn regions. In 1975 after the Vietnam war and then in 1996 after the first Iraq war, the U.S. used its parole authority to transport thousands of refugees and allies to Guam and Wake Island, where they went through vetting protocols and immigration processing before being resettled in the mainland United States.

Table: Past Uses of Parole During Evacuations

What is Humanitarian Parole?

Humanitarian Parole refers to parole that is granted based on an urgent humanitarian need. “Humanitarian parole” is also sometimes used by the media as a blanket term for any parole process that allows admission to individuals on an emergency basis, but there are other forms of parole that have been used for refugees or those in harm’s way. For example, in 2007, the Department of Defense used Significant Public Benefit Parole (SPBP) to quickly evacuate Iraqi translators who had worked with U.S. troops. The U.S. has also created special Refugee-Related Parole Programs (RRPPs) for specific groups of vulnerable individuals, including certain Central American minors and Cubans arriving by boat.

USCIS notes that there is no statutory or regulatory definition of either the “Humanitarian” or “Significant Public Benefit” parole authorities, and that on some occasions requests for parole may be granted for both urgent humanitarian reasons and significant public benefit reasons.

What are the eligibility requirements for parole?

Prospective applicants will only be granted parole “on a case-by-case basis for urgent humanitarian reasons or a significant public benefit.” Anyone can self-petition for parole at a U.S. embassy and sponsors inside the U.S. can also file on behalf of individuals who may be eligible.

Beyond these standardized guidelines, there are not strictly defined eligibility requirements for parole processes. Parole is always decided on a case-by-case basis, and separate application and vetting procedures are created for and tailored to each new parole program. For instance, parole for Central American minors with family members in the U.S. requires different vetting procedures and processing requirements than parole for Iraqi interpreters in 2007 or Afghan allies today. In all cases, parole applications are accepted or denied at the discretion of the U.S. government.

How is parole currently being used to evacuate Afghans?

Under Operation Allies Refuge, the Biden administration reportedly intends to use parole to evacuate up to 50,000 Afghans who may otherwise be eligible for either refugee or SIV status but have not yet completed their visa processing. As of August 30, it is not yet clear how many of these have already been evacuated. The administration is planning to end the evacuation effort by August 31 and is currently evacuating almost exclusively U.S. citizens.

Under the current parole process, Afghans undergo rapid processing at Hamid Karzai airport in Kabul before being taken to military bases in third countries, including Qatar, Bahrain, Germany, Kuwait, Spain, and the United Arab Emirates. Afghans who are in the late stages of the SIV process and have already gone through multiple rounds of security screening are provided with quick medical screenings and then flown to the U.S., where they are paroled in.

Afghans who are not in the final stages of the SIV process must wait — potentially for prolonged periods — in third countries to undergo robust security processing and vetting procedures. These vetting procedures are conducted by Department of Homeland Security (DHS) personnel, some already present at the military bases and some who have been rapidly deployed. The procedures include multiple rounds of biometric and biographic screening, and matching results with a variety of law enforcement and intelligence agency watchlists. Current and former intelligence officials with knowledge of the vetting procedures being used have described the process as “robust,” “competent,” and “secure.”

Beyond passing security and identity screens, the parameters of the current parole process are not yet fully clear. The U.S. has not yet specified the exact population of Afghans that is eligible for parole. On August 17, a bipartisan group of 46 Senators urged the administration to go beyond protections only for those who would be eligible for SIVs and P-2 status, which are both reserved only for those who directly supported U.S. efforts in Afghanistan. In their letter, the Senators called for the creation of “a humanitarian parole category specifically for women leaders, activists, human rights defenders, judges, parliamentarians, journalists, and members of the Female Tactical Platoon of the Afghan Special Security Forces.”

What benefits do parolees receive in the U.S.?

Parole temporarily shields individuals from deportation and — in some cases — allows them to apply for work authorization. Parole is separate from the visa admissions process, and it does not automatically confer immigration status or public benefits. In general, parolees must apply for more permanent immigration status to remain in the U.S. for longer than a short period. In the case of the evacuation of Kurdish allies in 1996, for example, parolees were immediately placed in asylum proceedings in order to receive more permanent protection. (In other past parole programs, Congress has passed legislation allowing individuals to access permanent status after they were paroled in.) Parole protections typically only last for a year, although certain programs have provided more extended protections or the ability to apply for “re-parole.”

Because parolees are generally not eligible for government benefits such as resettlement assistance, they often are required to secure financial support through a nongovernmental sponsor prior to admission into the U.S. However, during some previous emergency evacuations, additional funding to support arriving parolees can be authorized by either Congress or by the administration.

Under the Operation Allies Refuge parole program, Afghans are granted protection from deportation for two years and are eligible to apply for work authorization. The parolees are first housed temporarily in military bases in the U.S. In these bases, those who are in the final stages of the SIV process can complete the process and obtain SIV status. Others who may have been eligible for refugee status cannot apply for that status from inside the U.S. and must instead enter asylum proceedings or other visa processes.

Parolees are soon transferred to the care of refugee resettlement agencies across the country. Both the SIV and asylum process are severely backlogged and can take years to complete, and parolees receive no public benefits or government support beyond initial processing. As of August 26, resettlement agencies are supporting the resettlement of these Afghans largely through private donations, volunteers, and stretching already thin resources.

Table: Comparison of Federally Funded Benefits for Refugees, SIVs, and Parolees

What about Afghans who are in danger but were not evacuated?

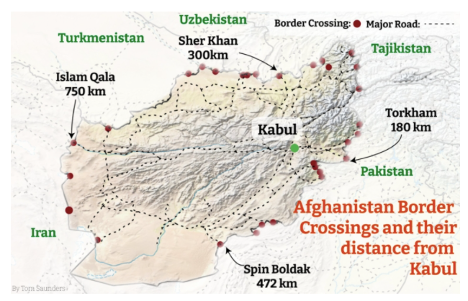

Afghans who are unable to be evacuated at the airport in Kabul may also travel to neighboring third countries such as Uzbekistan or Pakistan and apply for humanitarian parole (or P-2 refugee status, if eligible) at a U.S. embassy.

However, it has proven to be exceedingly difficult for Afghans to exit the country safely without U.S. support. Taliban checkpoints abound, and Pakistan — a traditional destination for Afghan refugees — has recently finished 1,640 miles of fencing along its border with Afghanistan, complete with 6 feet of concertina wire between two sets of 12-foot-tall chain link. Major crossing points along the border have been closed to refugees, including the Torkham gate near Kabul and Jalalabad.

To the west, the Taliban has seized control of certain crossing points with Iran (although some refugees have found safety there). Many Afghans attempting to flee through Iran to Turkey have been met with closed borders and increased enforcement. Refugees have faced a similarly cold response to the north, although in July a report suggested Tajik officials were preparing to host up to 100,000 Afghans.

Map: Afghan Borderlands

Source: I News

What more can the U.S. do?

There are multiple steps the U.S. can take to better protect Afghan refugees:

- Ensure parole eligibility is expanded to include vulnerable Afghan women and girls, human rights activists, journalists, and others most at risk.

- Work with Congress to provide sufficient additional resources to resettlement agencies and communities working to resettle Afghan parolees.

- Prolong evacuation efforts as long as possible and ensure safe passage to the Kabul airport to facilitate evacuations.

- Leave no one behind. To the extent evacuations by air are no longer possible, work to assist vulnerable Afghans in escaping to third countries.

- Apply diplomatic pressure to urge Pakistan and others to open their borders to refugees. Lead the international community in creating safe zones in neighboring countries to process claims for refugee status and humanitarian parole.