E-Verify is an electronic worker-verification system by which an employer checks to see if a newly hired employee is authorized to work in the United States. (See this fact sheet for more background on E-Verify.) The system is effective only if it can accurately screen out those not authorized to work and confirm those who are authorized.

When initially developed, the system’s error rate was unacceptably large, but over time it has been improving, and it is now small. However, because of the sheer number of individuals whom E-Verify checks, mistakes negatively affect many thousands of workers and employers.

Recent Statistics

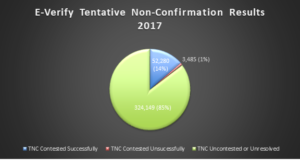

The most recent available statistics of the system’s performance are from the government’s fiscal year (FY) 2017.[1] Out of 34,853,666 cases, E-Verify returned a tentative non-confirmation (TNC) for 1.1 percent (or 383,390 cases).

Approximately 0.15 percent of the total, or 52,280 cases, were non-confirmations that were successfully contested (false negatives) — representing 13.6 percent of TNCs. Approximately 0.01 percent (3,485) of the total cases were contested but found to be accurate non-confirmations (true negatives). We cannot be certain about the remaining 324,149 non-confirmation cases because they were not contested or were otherwise unresolved for reasons such as incomplete paperwork.

Error Rates

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) has provided the erroneous TNC rate since 2006.[2] In 2017, 0.15 percent of E-Verify searches resulted in erroneous TNCs being issued. That is 13.6 percent of all TNCs, or 52,280 searches. This number is low because many employees do not contest erroneous TNCs. Many either do not understand the process for contesting an erroneous TNC or do not even know they can contest it in the first place.

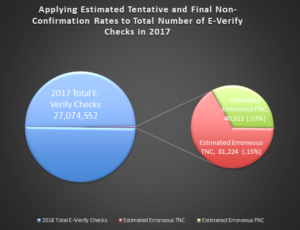

USCIS has not included the erroneous final non-confirmation (FNC) rate in their performance report since 2009. However, the Cato Institute estimated the erroneous FNC rate based off of its correlation to the TNC error rate.[3] In FY 2016, Cato estimated that 0.03 percent of all E-Verify queries ended with an erroneous FNC. That represented more than 3 percent of FNCs issued, meaning that for every thirty FNCs issued, more than one was likely to be erroneous.

If we apply these error rates to the FY 2017 data, erroneous TNCs would have been returned for more than 52,000 workers in FY 2017. And if 0.03 percent of queries resulted in erroneous FNCs, then more than 10,000 people who were eligible to work in the United States were barred from employment in error.

Number of Individuals Affected

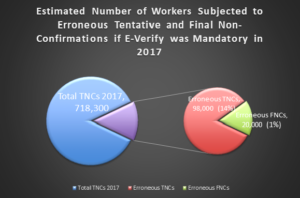

If E-Verify were mandatory and applied nationwide, the number of workers affected would more than double. In 2017, there were 65.3 million hires.[4] All of these would have to be run through E-Verify to check for work authorization. Applying the FY 2017 TNC rate to mandatory E-Verify this would result in 718,300 TNCs. Applying the error rates found by USCIS and the Cato Institute, upwards of 98,000 workers would be issued erroneous TNCs, with about 20,000 authorized workers barred from employment after an erroneous FNC.

Because millions of people are hired in the U.S. each year, a mandatory E-Verify system, even with an error rate as low as it is today, would result in tens of thousands of workers having to attempt to correct information in government databases. For many thousands more, inadequacies in the system would cause them to be barred from employment. A worker verification system that employers are required to use must address errors in the system so people who are entitled to work in the U.S. are not barred from doing so.

[1] USCIS, Performance (Updated 3/7/2018) https://www.e-verify.gov/about-e-verify/e-verify-data/e-verify-performance.

[2] Id.

[3] Cato Institute, E-Verify Has Delayed or Cost Half a Million Jobs for Legal Workers (May, 16, 2017) https://www.cato.org/blog/e-verify-has-held-or-cost-jobs-half-million-legal-workers.

[4] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey News Release (March 16, 2018) https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/jolts_03162018.htm (Accessed July 25, 2018).