What is eminent domain?

Eminent domain refers to the power of the United States government to acquire private property for public use.[1] The government may only use eminent domain if it provides “just compensation” to the property owners.[2] While eminent domain is a useful tool for the federal government to acquire private property for public use, critics have expressed concerns that it is subject to abuse and unduly undermines property rights.

The federal government has utilized eminent domain throughout U.S. history. Since at least 1875, the government has acquired private property by eminent domain to construct public buildings and projects (including border fencing), supply water, facilitate transportation (through railroads and, later, highways), aid in defense readiness, and carry out a variety of other projects.

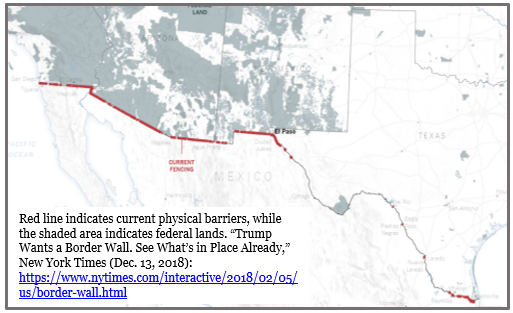

The federal government uses eminent domain to acquire private property along the Southern border to construct physical barriers, primarily border fencing. Because about 95 percent of the land in Texas is privately owned – only 1.8 percent is owned by the federal government – the government has recently used eminent domain in Texas to obtain land to construct border fencing and other physical barriers.

When can the federal government use eminent domain?

The federal government may use eminent domain to acquire private property under the following conditions:

- The acquisition of the private property is for a public use. The concept of public use in eminent domain is defined broadly and is generally equated with use that results in the furtherance of the public interest, such as – but not limited to – public safety, public health or the public’s benefit.

- The property owners are provided just compensation. The government must compensate the property owner for the fair market value of the property, even if the property is small and/or the government’s use does not significantly affect the owner’s economic interest.

How does eminent domain work?

When the federal government is considering acquiring private property through eminent domain, it first requests to survey the property to determine if the land is suitable for the government’s intended use. The request is generally the first sign that the government is interested in acquiring the property. If the land is suitable, the government sends an offer to purchase the property at an amount estimated to be just compensation based on the survey. The offer may also include a government-imposed deadline by which the property owner must decide to sell the land. While the landowner may attempt to engage the government in negotiations, the government is not required to participate in such discussions.

If the federal government and the landowner are unable to agree on the property’s value (or when the landowner is unwilling to sell the property at any price), the government moves in federal court to condemn the land. A condemnation allows the government to acquire the property through eminent domain.

To initiate a federal condemnation case, the federal government files a Declaration of Taking in the U.S. District Court in which the property is located. The declaration must include a statement of the public use and the authority under which the land is taken, among other requirements. Once the declaration is filed, the parties move forward to litigate the issues under consideration, namely the right to take the property and the amount of just compensation.[3] The government’s general standard for “just compensation” is the fair market value of the property at the time of the government’s acquisition. Fair market value is defined in the International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms as the price at which the property would be voluntarily sold between a buyer and seller. However, the government and landowner may disagree on whether the government’s offer constitutes the fair market value of the property, leaving that as a subject of the litigation. Property owners sued by the government do not have a right to be provided an attorney, so they must hire their own counsel.

Can the government seize the property promptly?

Yes. Filing the Declaration of Taking allows the federal government to seize the property as soon as a federal judge approves the order, potentially on the same day the declaration is filed in federal court and well before litigation is resolved. The declaration is filed pursuant to the Federal Declaration of Taking Act (40 U.S.C.§ 3114), which was enacted during the Great Depression to provide for expedited land seizures to allow public works projects to be promptly built. Under the law, the government may quickly obtain the title to the property and commence construction. The law also requires that the government immediately deposit a payment with the court to compensate the landowner for the fair market value of the property. The landowner can choose to accept the payment as a settlement or continue to litigate the matter, which can take years.

When has eminent domain been used along the Southern border?

The federal government used eminent domain to acquire private property along the Southern border after President George W. Bush signed the Secure Fence Act (H.R. 6061) on October 26, 2006. The bill, which passed with bipartisan support, directed the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to construct 700 miles of barriers along the Southern border. While most of the barriers were eventually built on federal lands along the Southern border thereby avoiding the need for eminent domain, some of the barriers were built on privately-owned land (mostly along the Rio Grande in Texas) and required the use of eminent domain.

Following the bill’s enactment, the federal government contacted private landowners along the border and provided them with 30 days to decide whether to sell their land. In the Rio Grande Valley in Texas, land agents closed 22 deals. However, over the following seven months, the government filed more than 360 eminent domain lawsuits against property owners who refused to sell their property, including 334 in South Texas. The targeted properties were mostly farms, but also included homes, golf courses and businesses.

Eminent domain was not used as often to build border barriers in California, Arizona and New Mexico because the federal government already owned most of the land in those border regions. The federal government eventually constructed around 650 miles of physical barriers along the U.S.-Mexico border, seizing private land in the Rio Grande Valley to build 50 miles of fencing.

How many eminent domain lawsuits are pending from the Secure Fence Act?

More than a decade after the original 334 cases were filed in South Texas after passage of the Secure Fence Act, there are approximately 60 to 70 eminent domain cases that are still pending. The cases remain unresolved mostly due to disagreements about the proper amount of compensation to the landowners.

The cases that have been resolved took an average of approximately three-and-a-half years to be settled. A DHS Office of Inspector General (OIG) report accurately predicted in 2009 that these eminent domain cases would be “a costly, time-consuming process” leading to substantial negotiation and litigation.

Does the federal government plan to continue seizing property along the Southern border to build barriers?

Yes. The federal government continues to send survey notices and purchase requests to landowners along the Southern border, in part because of the Trump administration’s efforts and issuance of a national emergency declaration to build a border wall. Landowners in the Rio Grande Valley in South Texas continue to receive notices from the federal government requesting access to survey their property, as well as to conduct soil tests and store equipment, the first step in the government’s acquisition of private property through eminent domain. A director with the Texas Civil Rights Project estimated in January 2019 that the government sent approximately 100 landowners new notices for the purpose of surveying how and where border barriers could be built. Earlier, in July 2018, Rep. Henry Cuellar (D-Texas) said that U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) had recently requested more than 200 survey notices in South Texas in Starr and Hidalgo counties.

The federal government is sending survey notices to a broad range of property owners. Noel Escobar, the Mayor of Escobares, Texas along the Rio Grande, received letters from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and CBP requesting his consent to survey his property to possibly build a border barrier. The Rio Grande City School District also received a letter in May 2018 identifying a mile of district property the government is considering acquiring for “tactical infrastructure, such as a border wall.”

In addition, as recently as January 2019, the Justice Department placed online job postings for new attorneys to handle border wall litigation in south Texas, an indication of upcoming litigation surrounding future property seizures.

What concerns have come up in connection with the use of eminent domain along the Southern border?

Critics have raised a number of concerns related to the use of eminent domain along the Southern border. An investigation conducted by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune into the use of eminent domain under the Secure Fence Act found that DHS and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) utilized the practice in a way that sidestepped laws designed to provide fair compensation to landowners, incorrectly valued some of the properties, and mismanaged cases.

Circumvented protections: The federal government issued waivers to sidestep requirements designed to ensure landowners receive fair compensation for their property. [4] Using its waiver authority, DHS unilaterally increased the threshold under which it must formally appraise a property and waived legal provisions that provided for initial negotiations with private landowners. In place of the formal appraisal, the government directed the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to review and assign values to the designated property.

Undervalued properties: The federal government initially offered compensation to landowners that did not represent the full value of the property. For instance, the government did not initially account for water rights associated with some of the properties, which can be worth more than the land itself. Once these errors became apparent, the government told the courts it would refile its settlements to account for the water rights, which led to delays in the compensation process.

The systematic undervaluing of properties also meant that landowners who could afford lawyers were able to negotiate much better deals. Such negotiated deals were, on average, triple the government’s initial offer. In contrast, property owners who could not afford attorneys, including many elderly and/or Spanish-speaking landowners, were far more likely to accept the government’s first offer. In addition, an NPR investigation of more than 300 eminent domain cases in the Rio Grande Valley found discrepancies in the amount of compensation provided to property owners after passage of the Secure Fence Act, suggesting some owners did not receive the full value of their property.

Mismanaged cases: According to the investigation conducted by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune, the federal government mismanaged hundreds of eminent domain cases. In certain cases arising from Secure Fence Act, the DOJ condemned and seized property without identifying the correct property owners and/or the property lines. These errors forced property owners to expend time and resources to correct the mistakes. In other instances, the government mistakenly compensated landowners for property they did not own and failed to recover such payments after realizing its mistakes.

***

[1] State and local governments can also utilize eminent domain.

[2] The Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution establishes, “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

[3] The procedures for the litigation are set forth in Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 71.1.

[4] The property must be appraised according to the standards set in the government’s Yellow Book, which includes standards for pricing land.