Introduction

Today, more than 9.2 million lawful permanent residents (LPRs) throughout the United States are eligible to naturalize and obtain citizenship. While naturalization provides significant economic benefits to the country and for new Americans, fewer than one million typically apply to naturalize each year. The LPR population in the United States continues to grow, yet millions of citizenship-eligible immigrants do not take the critical next step to become citizens.

Many people who are eligible to naturalize and desire to do so face significant barriers, including considerable citizenship application fees, required civics and English tests, and lengthy application processing times.

Over the last few years, COVID-19 restrictions, fiscal issues, a hiring freeze at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and other factors have exacerbated processing delays and naturalization backlogs and placed burdens on applicants and petitioners. While USCIS made progress in fiscal year (FY) 2022, completing 1,075,700 naturalization applications, more can be done to eliminate the naturalization backlog. To address continuing backlogs and delays, USCIS should work to remove unnecessary barriers to citizenship, commit to eliminating (not just reducing) naturalization backlogs, and develop streamlined processes for would-be citizens to reach decisions without lengthy delays. What USCIS has learned in reducing past and current naturalization backlogs should be applied to the numerous other backlogs within USCIS.

This report provides a general overview and analysis of USCIS naturalization backlogs looking at historic trends, contributing factors, and staffing levels, as well as examining USCIS’s record on responding to past backlogs. It concludes by providing proposals to make the processing of naturalization applications more efficient and setting a goal to timely reduce and eliminate the naturalization backlog.

Methodology

Data Collection

USCIS makes raw data on naturalizations public on its website, including the number of petitions filled, denied, approved, and pending at the end of each fiscal year. This report primarily focuses on USCIS naturalization data between FY 2010 and FY 2021 to examine current backlogs, while also going back to 1990 – prior to the creation of USCIS and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) – for a broader perspective. This report uses USCIS raw data, tables, and charts to analyze trends in a more comprehensive manner.

Unfortunately, not all USCIS reporting has been consistent – some data points (e.g., staffing levels) have been included in other reports or articles, making them more challenging to track. Similarly, staffing data was not broken down by programs, making it challenging to know the number of dedicated naturalization staff. To help address these issues, this analysis includes data compiled by other organizations, providing a more holistic overview of the situation surrounding naturalization.

Limitations

USCIS is moving toward digitizing much of its workflow but remains largely a paper-based agency. USCIS employees have to manually enter paper forms into agency computer systems, resulting in data entry errors. USCIS also states that its “data is transactional in nature” and subject to change at any time, including historic reports. This was most notable in its “Number of Service-Wide Forms” and its “USCIS Naturalization Data Tables,” which the agency periodically updates. This practice provides USCIS flexibility to change its data when reporting errors are uncovered. But this also can lead to information gaps and data inconsistencies. This report relied on secondary sources to fill in information gaps that USCIS was not able to provide on its website.

Analysis

The USCIS naturalization backlog has become a nightmare for many in recent years. A number of factors have contributed to the delays, including various Trump administration policies, the COVID-19 pandemic, and ongoing funding and staffing issues. At the end of FY 2021, more than 800,000 naturalization cases were pending before USCIS, a 60% increase from FY 2016.

Although such a large backlog may seem insurmountable, it is important to underscore that this is not the first time that USCIS has been challenged with reducing a sizeable naturalization backlog. USCIS faced even larger backlogs in the late 1990s. For example in FY 1998 the backlog was 2,371,796, largely the result of LPRs seeking to naturalize under the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). In FY 2007, the backlog reached 1,182,484, in response to a fee hike and the Legal Immigration Family Equity (LIFE) Act of 2000, which permitted certain immigrants to adjust status even if they had entered unlawfully, accrued unlawful presence, or worked without authorization. The FY 2007 backlog was also influenced by immigrants seeking to naturalize in response to the punitive impact of three bills passed in 1996 that targeted non-citizens, the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), and the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA). Both the FY 1998 and FY 2007 backlogs were successfully reduced after USCIS (or the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), its predecessor agency) surged resources and personnel to increase naturalization processing volume. Of note, these backlogs were driven by spikes in applications, which correspondingly created higher revenue that helped to finance the necessary increases in staffing and resources.

Data indicates that, on average, over the last 11 years, there have been more naturalization petitions filed than processed each year. Accordingly, a growing backlog has been inevitable. USCIS can do more to keep processing in line with the number of naturalization petitions filed. USCIS officials can use its decades of data to help shape its workflow and prepare for high volumes of application submissions in a given year. For example, historical data shows that major events like impending fee hikes, presidential election cycles, and new federal immigration legislation are likely to increase applications in a particular year. The flow of applications filed is often contingent on major events. While it still can be difficult to fully predict what may happen from year to year, USCIS can take steps to proactively ramp up capacity when such events are anticipated.

Another trend worth noting is that USCIS denial rates over the last decade have remained consistent – around ten to eleven percent. USCIS denies petitions if applicants fail the English or civics test, background checks, continuous residence requirements, or have paperwork shortcomings or other complications. While backlogs and denial rates in the immigration court system have risen – particularly in asylum cases – the data suggests that USCIS denial rates for naturalizations have remained fairly stable, with slight increases (one or two percentage points) since FY 2013.

Recent Naturalization Backlogs

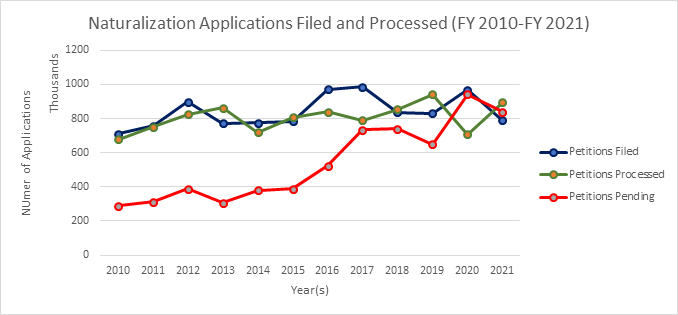

More recent patterns in naturalization applications filed and processed indicate useful information about USCIS’s timeliness and ability to respond to increases in applications filed and naturalization backlogs.

In FY 2012, USCIS saw a spike in both petitions pending (rising from 312,000 to 390,000) and petitions filed (rising from 756,008 to 899,162), which can be attributed to the presidential election that year. An increase in applications is typical in an election year and reflects the desire to vote, an important motivating factor for immigrants considering obtaining citizenship. While posing a challenge, the increase was managed well, with USCIS overcoming this backlog within a year. By FY 2013, the number of pending petitions fell back slightly below the FY2011 level.

Source: National Immigration Forum Analysis of USCIS Data

However, another spike, associated with the 2016 presidential election and a proposed fee increase, marked a turning point for USCIS. After FY 2015, the agency’s naturalization backlog increased significantly, and the agency failed to quickly respond to the increasing backlog for a number of years. In FY 2016, USCIS received more applications (972,151) for citizenship than it completed (839,093). That trend largely continued, with the number of pending petitions remaining above 800,000 in FY 2020 and FY 2021, more than twice the level it was at in FY 2015.

The centrality of immigration in the 2016 presidential election helped drive the number of naturalization applications that year. Candidate Trump’s hardline positions and rhetoric on immigration created uncertainty about the future of immigration in the U.S. and led many LPRs to file petitions to naturalize, both leading up to and after the election. Reflecting this trend, the number of pending petitions significantly increased by 135,608, from 388,832 in FY 2015 to 524,440 at the end of FY 2017.

The growth in the naturalization backlog starting in FY 2016 largely continued until FY 2022. The growth in this backlog has also impacted other backlogs and will continue to do so if the naturalization backlog is not reduced. For example, the Petition to Remove Conditions on Residence (Form I-751) has a median processing time of 19.5 months for FY 2023, according to USCIS. People who are married for less than two years and seek to receive a green card through marriage, are only given a conditional green card valid for two years. Before seeking to naturalize, these spouses of U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents are required to file Form I-751 in order to secure a regular green card. Form I-751 is used by USCIS to help ensure that a marriage is legitimate rather than a fraudulent “green card marriage.”

As the number of backlogged naturalization applications have increased, so too have the number of pending I-751 applications – reaching 270,925 as of the fourth quarter of FY 2022. This lengthy I-751 backlog is particularly concerning because it causes many spouses to postpone applying for naturalization. Normally, this population is eligible to apply for naturalization in three years based on marriage, instead of the standard five years, so the backlog in processing Form I-751 has a cascading impact in other parts of the naturalization system. While spouses filing Form I-751 technically can file their naturalization applications 90 days before they meet that three-year mark and have the removal of conditions (I-751) and naturalization applications (N-400) pending at the same time, concurrent filing has an inherent risk. If their Form I-751 is denied, the N-400 application is immediately denied as well, and all fees are lost. Therefore, many prospective applicants simply wait to apply for naturalization until after removal of conditions under Form I-751 has been approved, even though this can delay naturalization by months or years, further undermining the efficiency of the naturalization system.

Between FY 2016 and FY 2021, the number of pending naturalization petitions has averaged 737,921. However, unlike previous upticks in the number of pending petitions, USCIS did not immediately respond, instead waiting several years before taking targeted action. This post-2016 backlog was only worsened by subsequent events, including COVID-19 restrictions, funding shortfalls, and a hiring freeze, negatively impacting applicants and petitioners and leading to a crisis state.

COVID-19 Pandemic

In FY 2020, USCIS received 967,755 applications for citizenship, and completed only 708,863 applications. With USCIS operational capacity severely limited after March 2020 and the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, the number of completed applications in FY 2020 was 232,519 fewer than in FY 2019 and represented the lowest number of naturalization applications completed in the proceeding nine years.

Even as the pandemic limited USCIS functions and promoted the search for alternative processes, the 2020 presidential election and planned USCIS fee change, that was ultimately blocked by a federal judge, increased the number of citizenship applications filed in FY 2020 by 137,195 from FY 2019 levels-going from 830,560 to 967,755.

The COVID-19 pandemic left USCIS with 942,669 pending cases at the end of FY 2020, the highest levels since 2007. While USCIS made some initial progress reducing this backlog in FY 2021, this number remained high with 839,635 pending cases. While USCIS cannot be blamed for the myriad complications and delays arising from a global pandemic, it can be faulted for failing to act years earlier. USCIS can also be blamed for failing to prepare for what should have been an anticipated fee- and election-related influx of applications by properly allocating resources and personnel. This inaction made the impact of the pandemic worse than it needed to be.

Staffing Levels

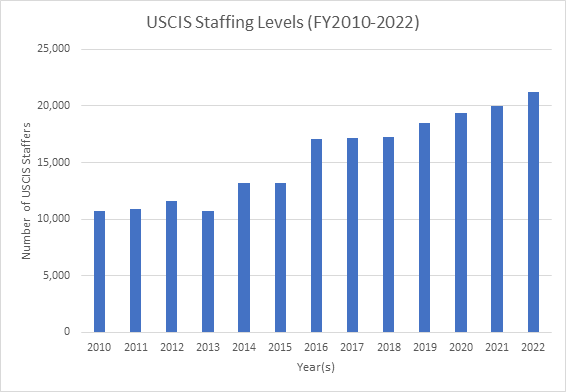

Increased staffing levels have been a critical tool in addressing naturalization backlogs. Indeed, USCIS hiring and allocating additional staff to handle naturalization processing continues to be a clear and effective means to address naturalization backlogs. Unfortunately, USCIS does not provide data that specifically addresses the number of staff it assigned to work on naturalization processing, instead only providing overall staffing numbers for the entire agency in most cases.

Even as the naturalization backlog has climbed in recent years USCIS staffing has grown, nearly doubling since 2010. Despite a Trump-era hiring freeze announced in February 2020 (shortly before COVID-19 pandemic-related closures in the U.S.), a hiring surge for asylum officers and support staff was instituted to deal with the asylum backlog, causing USCIS to nevertheless grow overall in FY 2020. However, few of the new hires, most of whom were asylum officers, spent significant time working to address the growing naturalization backlog.

This growth in overall USCIS staffing (but not necessarily naturalization staffing) continued even as the COVID-19 pandemic led some internal USCIS leaders to raise concerns about the agency’s falling revenues. In June 2020, the Trump administration announced that it would furlough up to 70 percent of USCIS’s workforce, purportedly due to COVID-related reductions in revenues. Critics raised doubts about the extent of the revenue declines, questioning whether the planned furloughs were a policy decision by an administration that was skeptical of legal immigration. Subsequently, after congressional pushback and further examination into the agency’s fiscal health, USCIS cancelled the furlough, claiming that it was able to make alternative “unprecedented spending cuts” as revenue increased.

Source: National Immigration Forum Analysis of USCIS Data

Notably, despite the pandemic, the number of naturalization applications filed in FY 2020 actually increased over FY 2019, likely due to the forthcoming 2020 presidential election, and the corresponding revenue from naturalization fees improved the agency’s bottom line. This occurred even as the pandemic limited some USCIS operations and reduced submissions of other applications.

Even though USCIS ultimately averting a major furlough, the threat led some employees to leave the agency and seek employment elsewhere. These departures increased a number of USCIS backlogs and were particularly harmful when paired with the Trump-era hiring freeze that prevented many of the vacancies from being filled. Through all this the agency’s overall staffing increased as specific personnel were hired such as asylum offices in FY2020. While the Biden administration lifted the hiring freeze, many vacancies have persisted. As USCIS continues to rebuild its workforce and fill vacancies, the difficulty in filling these positions indicates that the agency will also need to make additional changes beyond increasing staffing to streamline the naturalization process.

Efficiency Gains and Funding Developments

With the pandemic closing USCIS offices and limiting in-person services, the agency searched for alternative ways to manage its workflow. Some of the alternative efficiencies identified and implemented by USCIS included expanding the use of virtual interviews, reusing fingerprints from other processes, and expanding the number of application processes that could be done digitally, reducing the reliance on paper. With COVID-19 reducing demand for some USCIS services, the agency expanded the use of premium processing to apply to other services, helping to generate more revenue to keep the agency afloat.

The rollout of these new practices holds promise for improving efficiency. USCIS should continue expanding new practices that prove effective in improving and streamlining services. For example, increasingly moving to digital filing and processing has been long overdue for USCIS, and these efforts may yield significant efficiency gains.

The pandemic also has created an opportunity to examine USCIS’s funding model. While USCIS has been predominately a fee-funded agency, COVID-19 highlighted the fragility of that structure. While demand for naturalization increased, the availability of USCIS services decreased dramatically, leaving the agency with fiscal challenges. Congress must reassess USCIS’s funding model to address not only current but also long-term realities, including providing annual appropriations for USCIS. Rather than remaining a primarily fee-funded agency, USCIS should be funded by a combination of annual appropriations and the fees it collects.

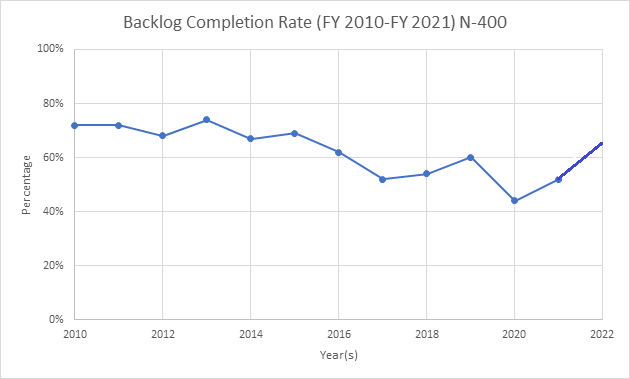

Backlog Completion Rates

An effective method to evaluate how efficient USCIS has been in processing its backlog of applications is to measure its backlog completion rate for naturalization applications. Backlog completion rate refers to the percentage of applications from proceeding years and the current year that have been completed. For example, if USCIS processed every citizenship application it received in the current year plus the applications that were pending from the previous year, that would yield a backlog completion rate of 100%. The lower the completion rate, the less progress made toward reducing and eliminating the backlog.

Source: National Immigration Forum Analysis of USCIS Data

USCIS achieved a backlog completion rate of 74 percent in FY 2013 and this number trended downward through FY 2020, only beginning to rebound in the past two years. There was a 10-point drop in backlog completion between FY 2016 and FY 2017 (62% to 52%), coinciding with the first year of the Trump administration and the beginning of the increase in the naturalization backlog.

In FY 2019, the backlog completion rate rose to 60 percent, but plummeted to 44 percent in FY 2020, amid pandemic-related processing slowdowns and the pre-pandemic Trump-era hiring freeze announced in February 2020. As operations began to return to normal and the Biden administration came into office in FY 2021, there was an 8-point increase in the backlog completion rate from FY 2020 to FY 2021 (44% to 52%), similar to Trump-era pre-pandemic levels. Devoting more resources and personnel toward naturalization and taking steps to speed up processing, USCIS completed its highest number of naturalizations (1,023,200) in nearly 15 years, leading to a backlog reduction rate of 62 %.

However, while representing progress over FY 2020, unless the backlog completion rate rises dramatically, this means that backlogs will continue to grow at unsustainable rates. USCIS will need to find a way to significantly raise the backlog competition rate to effectively reduce the naturalization backlog. Backlog completion rates from the last decade – in the 60-75% range – will not be sufficient to address the backlog. USCIS will need additional resources to hire additional staff and implement more efficient processing to increase these rates and eliminate its naturalization backlog altogether.

To further these gains, USCIS should take additional steps to determine the level of staffing needed to increase the backlog reduction rate and eliminate the backlog entirely in the coming years. The agency should begin collecting data on the marginal impact of each new full-time employee focused on naturalization processing. With that data, USCIS will be better situated to set staffing levels to eliminate the naturalization backlog. Elimination of USCIS backlogs, naturalization-related and others, should be a top priority for the agency.

Learning from Historic Backlogs

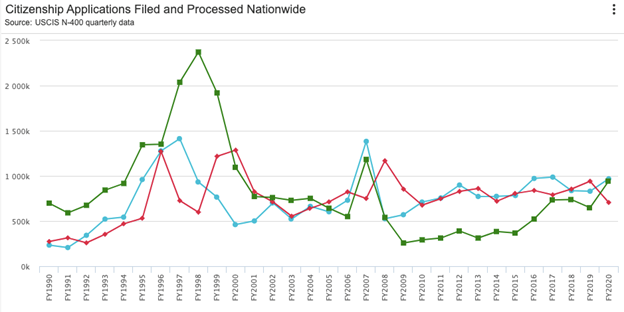

After the passage of IRCA in 1986, 2.7 million unauthorized immigrants received legal permanent residence status. Over time, these individuals would be eligible for citizenship and in turn increase the pool of citizenship applications filed. By the mid-1990s, people who obtained LPR status under IRCA became eligible to naturalize and the naturalization backlog began an upward trend.

However, naturalization has also been spurred on by impending immigration crackdowns. Three federal laws passed in 1996– the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), and the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) – led many LPRs to adjust status and obtain citizenship, adding to the naturalization backlog. These laws increased penalties for various immigration offenses and limited access to public benefits for non-citizens, making citizenship more appealing for those who qualified and increasing naturalization filings. During the period FY 1995 to FY 2000, there was an unprecedented surge in naturalization applications. Between FY 1995 and FY 1998, the volume of naturalization applications filed stayed above 900,000 and peaked at a record-high 1.4 million in FY 1997. Additionally, the backlog between FY 1995 and FY 2000 remained above 900,000 and peaked at about 2.4 million in FY 1998. The Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), USCIS’s predecessor agency, responded by dedicating significant resources to address the backlog. In 1998, the INS officially requested additional appropriations from Congress to reduce the naturalization backlog, in addition to raising agency revenues through a proposed citizenship fee increase from $95 to $225. The INS committed to adding 290 people to its staff with such funding. In FY 1998 INS actually secured an increase of $163 million to address the naturalization backlog. Using this funding to hire additional personnel, the INS was able to process significantly more applications in FY 1999 and FY 2000, bringing the backlog back down to just above 1 million by FY 2000, a level below where it had been in FY 1995.

In FY 2007, USCIS experienced an increase in naturalization applications as a result of an impending 80% increase in naturalization fees, and the earlier passage of the LIFE Act of 2000.

The LIFE Act made it easier for many immigrant family members and workers to obtain LPR status, even if they had entered unlawfully, accrued unlawful presence, or worked without authorization. The LIFE Act also encouraged those LPRs eligible for citizenship in five years, to naturalize in FY 2007 and FY 2008. The resulting increase led the naturalization backlog to rise above one million, not as severe as the backlog in the mid-1990s, but still significant. According to the Migration Policy Institute, USCIS addressed this backlog by expanding hours, detailing more staff to processing centers, hiring additional contract workers and employees- including retired USCIS workers. In addition, USCIS increased staffing by almost 600 positions between FY 2007 and FY 2008, although not all of those staffers were devoted to addressing the naturalization backlog.

Through dedicating funding, resources, and personnel to addressing the backlog, USCIS successfully brought the number of pending naturalization cases down from 1.1 million at the end of FY 2007 to 230,000 in FY 2009, resulting in one of the lowest backlogs in 30 years. INS and USCIS handling of previous backlogs provide evidence that when the agency dedicates resources to citizenship application surges, it has been able to significantly reduce the backlog within one or two years.

![]()

Source: 2021 State of New American Citizenship Report. Boundless Immigration. “Backlogs in Context.”

On a promising note, we are starting to see a similar management focus on reducing current backlogs, most recently in FY 2022 when attention was given to the naturalization backlog. The USCIS Fiscal Year 2022 Progress Report notes, “Although there is much work ahead to deliver timely decisions to all customers, USCIS continues to apply every workforce, policy, and operational tool at its disposal to reduce backlogs and processing times.” In FY 2022, the number of USCIS employees increased by 1,250 as compared FY 2021, rising from 20,003 to 21,253, although only a fraction of those employees focused on naturalization. In any event, USCIS should continue to increase staffing levels focused on the naturalization backlogs, make operational improvements to increase efficiencies, and leverage technical automation to prevent future backlogs.

Conclusion

The lessons learned from the naturalization backlogs that have plagued USCIS over the years have made it essential that the agency act to address this issue. USCIS must devote resources, add personnel, create new, and expand on existing, efficiencies to reduce the current backlog within two years and then eliminate the cycle of naturalization spikes and corresponding backlog reductions.

USCIS has demonstrated that it is capable of reducing backlogs and in a relatively short period of time when it prioritizes that reduction. However, returning the backlog to manageable levels is only the first step. Reducing a backlog without permanently controlling the process by securing adequate staff and expanding capacity leading up to presidential elections, fee schedule changes, and legislative changes only means we will continue to see repeated cycles of backlog increases and reductions that adversely affect applicants and petitioners. In the present, the impending fee changes and presidential election of 2024 should be taken into consideration. USCIS must control this backlog cycle such that it does not discourage the pool of 9.2 million eligible LPRs from applying for naturalization in an efficient and timely manner.

USCIS has a menu of options that can be used to tackle this issue and improve its processes overall. Those options include the following:

- predicting increased caseloads associated with recurring events,

- responding promptly to backlog increases,

- increasing the number of dedicated naturalization staff based on a manageable caseload size,

- detailing internal staff to help manage a growing number of naturalization applications,

- hiring additional contract workers and employees to handle backlogs,

- expanding hours, and

- increasing efficiencies through expanding the use of virtual interviews, reusing fingerprints, shortening applications forms, digitizing fee waivers, and allowing for e-filing of naturalization applications from third-party databases.

USCIS should begin implementing these options and also work with Congress to obtain appropriations specifically earmarked for addressing and eliminating current and future naturalization backlogs. USCIS should also take steps to ensure that backlogs are prevented in the first place – including surging personnel and resources before elections, planned fee changes, and other predictable occurrences. USCIS should hire additional dedicated staff to eliminate the current backlog within two years, retain sufficient staffing to permanently prevent the reoccurrence of a backlog, and digitize and modernize its processes.

USCIS has demonstrated that it is fully able to reduce such backlogs when it commits to doing so and is provided adequate resources. INS and USCIS experienced record and unprecedented naturalization backlogs in the mid-1990s, and again a decade later, yet took prompt and effective action to reduce those backlogs. Facing a growing backlog more recently starting in FY 2016, USCIS acted in FY 2022. USCIS naturalized more than one million new U.S. citizens and achieved a backlog completion rate of 62 percent. The progress report USCIS published for FY 2022, and past USCIS backlog reduction actions, are evidence that this goal of eliminating its current naturalization backlog, and preventing future backlogs, is possible. USCIS can and should take prompt action to make this is reality.

The National Immigration Forum would like to thank Gilberto Calderin, policy intern, for his extensive contributions to this report.