Who are Dreamers?

Dreamers are undocumented immigrants who came to the United States as children. They grew up and have lived in the U.S for most of their lives. Many Dreamers have attended school and obtained postsecondary degrees, worked and contributed to the U.S. economy, and started families with U.S. citizen spouses and children.

For most Dreamers, the U.S. is the only home they have known. Despite this fact, no pathway currently exists for most Dreamers to gain lawful residence or citizenship in the U.S.

What is DACA?

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) is a program that provides work authorization and protection from deportation to certain Dreamers. It does not provide a pathway to citizenship or permanent lawful status.

To enroll in DACA, a Dreamer must have come to the U.S. before their sixteenth birthday and continuously resided in the U.S. since June 15, 2007, and they must meet other requirements regarding age, education, immigration status, and no criminal activity. Recipients must submit renewal requests every two years.

As of June 30, 2024, 535,030 Dreamers held active DACA status. More than one-quarter of DACA recipients live in California, with significant populations also in Texas (89,360), Illinois (28,330), New York (21,250), Florida (21,170), North Carolina (20,550), and Arizona (20,170). A majority of DACA recipients—roughly 80 percent—were born in Mexico, but a substantial portion were born in El Salvador (21,100), Guatemala (14,220), and Honduras (13,050). DACA recipients come from 170 different countries. The average DACA recipient came to the U.S. at around seven years of age and is now 32.

In recent years, challenges to DACA’s legality have volleyed the policy back and forth in the courts. Since a July 2021 federal court ruling, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has been unable to accept new DACA applications; however, those with existing DACA protections may continue to apply for renewal.

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals is again reviewing DACA’s legality. The case will likely be appealed to the Supreme Court, potentially pushing a decision to spring 2026. This litigation requires swift action from Congress to provide a permanent solution for Dreamers, as court rulings could eliminate DACA protections altogether.

How many Dreamers live in the U.S.?

Though it is difficult to determine exact figures on how many Dreamers reside in the U.S., several estimates provide a snapshot of the population.

- DACA. DACA recipients are a sub-group of the Dreamer community. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) indicates that there are about 535,000 DACA recipients in the U.S. As noted above, USCIS is not allowed to process new initial applications for DACA.

- DACA-eligible. Many estimates of the Dreamer population take into account only those who meet DACA eligibility criteria. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimated that 1.2 million Dreamers would be immediately eligible for DACA in 2023 if the program continued to accept renewals from current recipients and started accepting new applications. This estimate suggests that over half a million undocumented individuals in the U.S. meet the eligibility criteria for DACA but are not enrolled in the program, likely because they faced financial obstacles (online DACA renewals cost $555) or because they were too young to apply before the courts blocked USCIS from processing new applications. MPI states that an additional 300,000 Dreamers meet all DACA eligibility requirements except those relating to education.

- Dreamers. Not all Dreamers are eligible to enroll in DACA, however. In 2018, the Washington Post noted that as many as 3.6 million undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. had arrived younger than age 18, including those ineligible for DACA. A report using American Community Survey (ACS) data estimated that the Dreamer population consisted of at least 3.4 million individuals in 2023.

Dreamer Legislation: An Overview

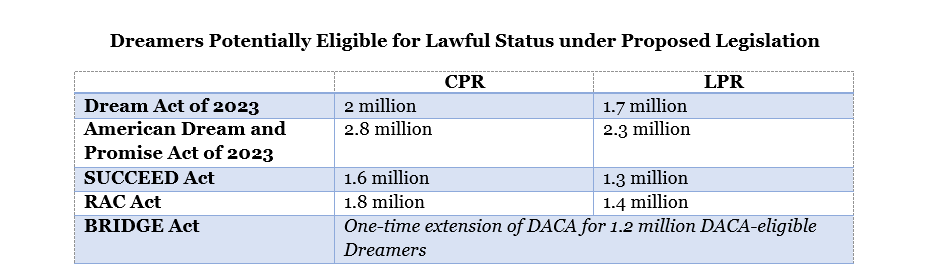

Though Congress has yet to pass a permanent legislative solution for Dreamers, several proposed bills over the years have sought to provide Dreamers with the opportunity to obtain lawful status and eventually U.S. citizenship if they meet certain requirements. Organizations provided estimates of the number of Dreamers who would benefit from these proposals.

Dream Act of 2023 (S. 365): This bipartisan bill would grant conditional permanent residence (CPR) to Dreamers who entered the U.S. under age 18, who are enrolled in school or have finished high school or its equivalent, and who have not committed certain crimes. Certain CPR recipients could also become eligible for lawful permanent residence (LPR), or green-card status, if they obtain higher education, complete two years of military service, or work for several years. After maintaining LPR status for five years, a Dreamer could apply for U.S. citizenship.

Estimates of the number of Dreamers who would gain permanent residence under the Dream Act vary. The American Immigration Council estimates that 1.6 million Dreamers would be immediately eligible and, all together, 1.9 million would be potentially eligible for CPR if the bill were enacted. Another estimate states that 2.3 million would eventually have a path to citizenship through the Dream Act.

Finally, MPI estimates that 3 million Dreamers meet the requirements for age at entry and U.S. residence under the nearly identical Dream Act of 2021, while 2 million would be eligible for CPR status and eventually 1.7 million would be eligible for LPR. The attrition rate is due to the increasing eligibility requirements—education, work or military service-based—that accompany each next step in the bill’s legalization process.

American Dream and Promise Act of 2023 (H.R. 16): This bipartisan bill would grant DACA recipients and other Dreamers protection from deportation and a pathway to permanent legal status in the U.S. Dreamers who entered the U.S. before age 18 could apply for CPR if they have not been convicted of certain crimes, are enrolled in school or have earned a high school diploma, have been admitted to a postsecondary institution, pay a fee, and pass background checks. Dreamers who receive CPR could hold this status for up to 10 years and apply for LPR upon meeting other requirements for education, military service, or employment.

MPI estimates that 2.8 million Dreamers would meet the age at entry and residence requirements for CPR status, and 2.3 million Dreamers would likely progress to LPR status. The USC Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration estimated that under a 2019 version of this bill, 1.8 million Dreamers would be immediately eligible for CPR status, and an additional 300,000 would eventually become eligible.

SUCCEED Act (S. 1852): Introduced in 2017, the SUCCEED Act would allow Dreamers who came to the U.S. before age 16 to earn CPR status and eventually LPR status through a 15-year process. Dreamers could earn CPR for five years upon passing government background checks and meeting certain age, residency, and education requirements, then extend CPR for an additional five years upon meeting requirements for higher education, employment, or military service. After maintaining CPR for 10 years, a Dreamer could apply for LPR status.

MPI estimated in 2017 that 2 million Dreamers met the requirements for age at entry and U.S. residence under the SUCCEED Act, while 1.6 million would be eligible for CPR and 1.3 million would eventually be eligible for LPR.

Recognizing America’s Children (RAC) Act (H.R. 1468): Introduced in 2017, the RAC Act would allow Dreamers who came to the U.S. before age 16 to earn CPR if they pass a government background check and either earn a high school diploma, have a valid work authorization document, demonstrate intent to enter the military, or are accepted into a higher education institution. After maintaining CPR status for five years, Dreamers who meet additional employment, military, or education requirements can extend CPR and apply for LPR.

MPI estimated in 2017 that between 2.4 million and 3.2 million Dreamers met the requirements for age at entry and U.S. residence under the RAC Act, while 1.8 million would be eligible for CPR and 1.4 million would be eligible for LPR.

BRIDGE Act (S. 128): Introduced in 2016, the bipartisan BRIDGE Act would provide a one-time temporary work authorization and protection from deportation to DACA-eligible Dreamers. This “provisional protected presence” would last up to three years. In addition to qualifying for DACA, applicants would need to pay a fee, pass a background check, and meet requirements for age of arrival and U.S. residence.

Because this proposal applies only to DACA-eligible individuals, about 1.2 million Dreamers would likely qualify for the one-time provisional protected presence under the BRIDGE Act if it were enacted today.

Contributions of Dreamers

Dreamers make critical contributions to the U.S. economy. Those covered by the proposed Dream Act of 2023 contribute $45 billion to the economy each year through their wages and an additional $13 billion in federal, payroll, state, and local taxes. DACA recipients’ tax contributions total $3.4 billion more per year than they receive in benefits, and they pay $760 million in mortgage payments annually. The DACA-eligible population holds $31.9 billion in spending power.

Nearly half of Dreamers work in industries facing several labor shortages in the last few years, including construction, manufacturing, food services, transportation, and healthcare. During the Covid-19 pandemic, more than 30,000 Dreamers responded to the crisis as nurses, physician’s assistants, or other health professionals. Nearly 10% of DACA recipients indicate that they have started their own businesses.

Dreamers are deeply integrated into their American communities. One-fifth of potential Dream Act beneficiaries are parents of at least one U.S. citizen child, meaning that around 750,000 U.S. citizen children have a Dreamer parent. One in ten Dreamers is married to a U.S. citizen. Among DACA recipients, 31%, or roughly 167,000 individuals, own homes.

Urgency for a Legislative Solution

Amid frequent court challenges to DACA’s legality, a legislative solution for Dreamers remains urgent. On September 13, 2023, the U.S. District Court for the Southern Court of Texas ruled that the program is unlawful, echoing a similar judgment by the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in October 2022. The Biden administration appealed this decision, and the Fifth Circuit Court is again reviewing the case. DACA’s fate may eventually reach the Supreme Court.

DACA recipients have remained in limbo for years, with many concerned about what will happen to the lives they have built in the U.S. should the policy be overturned. DACA recipients also face uncertainty as they wait for renewal approval every two years.

Additionally, legislative action is necessary because DACA protections do not cover all Dreamers. The youngest Dreamers eligible for DACA would have been born just before June 15, 2007, making them now 17 years old. Thousands of Dreamers residing in the U.S. were born after this date. Many otherwise eligible Dreamers were younger than 15 when the courts blocked new applications from being processed, denying them the chance to apply when they turned 15. In 2022, the estimated number of undocumented children under age 18 ranged from 850,000 to 1.2 million; most of these children are ineligible or unable to apply for DACA protections despite forming a significant portion of the Dreamer population.

Conclusion

Dreamers have resided in the U.S. since they were children, enriching American schools, workplaces, and communities despite their uncertain legal status. While DACA has provided temporary protection and work authorization for many, it leaves hundreds of thousands of others without coverage and offers no path to permanent residency or citizenship for those who have it. Congress should preserve Dreamers’ contributions to the U.S. by enacting a permanent solution that allows Dreamers to obtain legal status.

.

The National Immigration Forum would like to thank Emma Campbell, Policy and Advocacy Intern, for developing this explainer.

.