INTRODUCTION

The term “deferred action” has become a partisan flashpoint since President Obama announced his package of executive actions on immigration in November 2014. Two programs at the center of the executive actions – an expanded Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (“expanded DACA”) and the new Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (“DAPA”), have been particularly controversial, serving as the subject of high-profile Supreme Court litigation and the target of Republican-backed repeal legislation.

President Obama’s executive actions have been the subject of much debate and analysis in the political realm, the court of public opinion, and the media. However, despite executive action’s prominent role in the nation’s political and legal debate over immigration, the understanding of “deferred action” has all-too-often been lacking. Deferred action was a longstanding cornerstone of American immigration policy decades before the Obama Administration made its executive action announcement in November 2014. Expanded DACA and DAPA are far from being the only cases in which the government had relied on deferred action.

WHAT IS DEFERRED ACTION?

According to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), deferred action is defined as “a discretionary determination to defer a deportation of an individual as an act of prosecutorial discretion.”

- Deferred action can be granted by USCIS or a federal immigration judge.

- USCIS will not initiate removal proceedings against individuals who have been granted deferred action.

- Deferred action does not confer lawful status on an individual and does not provide a path to permanent residence or citizenship.

- DHS considers individual recipients of deferred action to be lawfully present in the United States during the temporary period in which deferred action is effective, but a grant of deferred action does not excuse any prior or subsequent periods of illegal presence in the country.

- DHS is permitted to terminate or renew a grant of deferred action at any time based at its discretion.

- Existing regulations (8 CFC §274a.12(c)(14)) permit an individual receiving deferred action to obtain employment authorization based on proof of his or her “economic necessity for employment,” which allows an individual to support himself or herself during the period in which executive action is effective. Work authorization is valid during the entire duration of deferred action.

WHERE DID THE CONCEPT OF DEFERRED ACTION ORIGINATE?

The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) of 1952 introduced a comprehensive plan for immigration and naturalization, specifying certain categories of “aliens” who are inadmissible to and removable from the country. DHS and its predecessors, including United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), have been deporting unauthorized immigrants for more than a century and have applied discretion to determine whether to pursue or defer particular deportations during that time.

The concept of “deferred action” has existed as long as federal immigration authorities have applied prosecutorial discretion to prioritize some removals over others. In the immigration context, prosecutorial discretion may be exercised at any stage of an immigration case.

Some experts credit the case of John Lennon (of Beatles fame) with bringing the doctrine to prominence, after his immigration attorney successfully persuaded the INS to formally grant him deferred action in the early 1970s.

Lennon, who had overstayed his visa and previously had a marijuana conviction in the United Kingdom, requested to be classified as a “non-priority alien” by INS. This status represented the lowest possible priority for the INS action, and was traditionally given to undocumented immigrants for whom departure from the United States would result in extreme hardship. Although INS officials regularly designated low-priority cases in this manner, effectively halting deportation for these otherwise deportable immigrants, it did so under a veil of secrecy and declined to even admit such a practice existed.

The non-priority status used in Lennon’s case later came to be known as “deferred action.”

In addition to deferred action, immigration authorities may exercise prosecutorial discretion in other ways, including decisions to terminate or administratively close removal proceedings, to grant stays of removal, or to decline to issue a charging document.

UNDER WHAT CIRCUMSTANCES IS DEFERRED ACTION GRANTED?

A. On an Ad Hoc Basis

Today, immigration officials commonly grant deferred action in individual cases, often for humanitarian purposes, and occasionally they apply deferred action to provide discretionary relief from deportation to individuals falling under specific categories.

Deferred action in these sorts of “one-off” cases is often referred to as “ad hoc deferred action.” According to recent guidance from the White House Office of Legal Counsel (“OLC memo”), DHS personnel may recommend ad hoc deferred action when they feel relief is warranted. However, an unauthorized immigrant can also apply for this relief by submitting a written request to USCIS disclosing why he or she is seeking deferred action, together with other supporting documentation, proof of identity, and other evidence.

Ad hoc deferred action is most commonly granted for humanitarian reasons, such as when undocumented parents are permitted to remain in the United States to care for their sick U.S. citizen children.

For example, ad hoc deferred action has been granted to a Guatemalan parent with a U.S. citizen child with significant medical issues, a 13-year-old boy from El Salvador who was traumatized by witnessing two gang killings in his home-town, and to a Nigerian whose mother was undergoing treatment for cancer. Another example is a 15-year-old girl who was the sole survivor of a devastating car accident that killed her parents, older sister, and uncle. The girl, a DREAMer who lived in the U.S. with her family since arriving a toddler from Brazil, obtained deferred action status – avoiding potential removal – prior to the announcement of DACA in 2012.

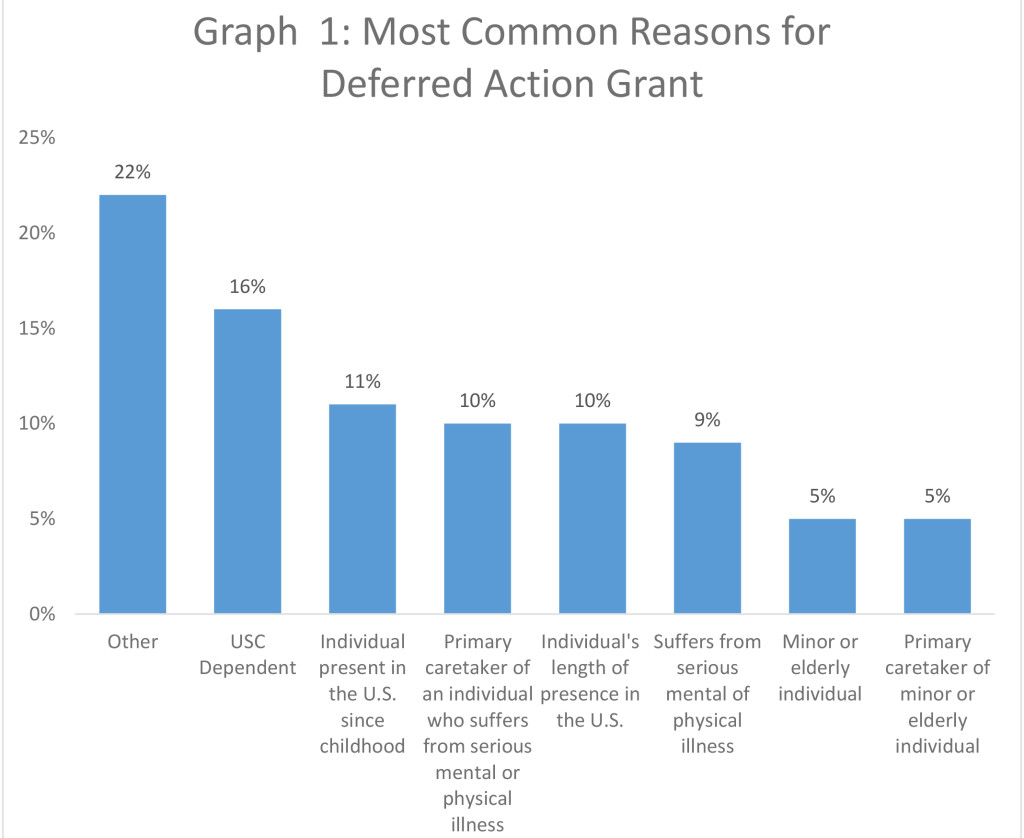

A study by Penn State University – Dickinson School of Law’s Professor Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia examined deferred action data from 24 U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) field offices covering the time period October 1, 2011, to June 30, 2012. The dataset covered 698 cases in which a request for deferred action was considered. In 324 of these cases, deferred action was granted, typically where the recipient of relief meets at least one of the following five conditions: (1) supports a U.S. Citizen (USC) dependent, (2) has maintained presence in the United States since childhood, (3) serves as primary caregiver of an individual who suffers from a serious mental or physical illness, (4) has maintained presence in the United States for several years, and (5) suffers from a serious mental or medical care condition. The results are summarized in Graph 1 below.

Source: Wadhia, Shoba Sivaprasad. My Great FOIA Adventure and Discoveries of Deferred Action Cases at ICE. Thesis. The Pennsylvania State University, 2013. N.p.: Pennsylvania State U, The Dickinson School of Law, 2013. Social Science Research Network. Web. 12 Apr. 2016.

B. Targeting Specified Groups

ICE and its predecessor INS have also broadly applied prosecutorial discretion to provide discretionary relief from removal targeted towards to particular groups of unauthorized immigrants. These broad-based grants of relief include tools such as parole, temporary protected status, deferred enforced departure, and extended voluntary departure.

This authority has been applied at least 20 times since the 1970’s, and since the late 1990’s, there have been at least five occasions when INS and/or DHS applied deferred action to target specified categories of immigrants. Prior to the Obama Administration’s actions, the largest group of people afforded deferred action was estimated to be as many as 1.5 million — about 40 percent of the then-unauthorized population — through the “Family Fairness” policy. This policy was implemented to keep families together, specifically the spouses and children of those who were legalized under the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986.

Similarly, in 1997, INS introduced a program of making deferred action available to self-petitioners under the Violence Against Women Act of 1994 (“VAWA”). VAWA authorized undocumented victims of domestic violence at the hands of their U.S. citizen (USC) or Legal Permanent Resident (LPR) spouses or parents to self-petition for lawful immigration status. Under VAWA, these individuals did not have to rely on their abusive family members to sponsor their request for relief and sign the petition on their behalf, instead the applicants themselves could file an application for immigration relief. Under this program, immigration officers approving VAWA self-petitions were required to determine on case-by-case basis whether the individual was eligible for the deferred action status.

To apply for deferred action as a VAWA self-petitioner, an individual must file Form I-360 and submit it together with supporting documentation, including evidence of the abuse or extreme cruelty and proof of relationship to the abuser. Under approval of the VAWA petition, the applicant is first granted deferred action but later he or she may apply for lawful permanent resident status. The time delay between grant of the deferred action and application for LPR status depends on the situation of the given petitioner. Spouses of USCs, parents of adult USCs or unmarried minor children of USCs may apply for the LPR status immediately, but spouses and children of LPRs must apply in accordance with the so-called “family preference system,” and it’s corresponding “country caps.” Accordingly, there can be a significant a waiting period for spouses and children of LPRs attempting to apply for LPR status. So that these qualifying VAWA self-petitioners can avoid deportation while awaiting determinations on their applications, deferred action serves as a valuable tool for these individuals.

While the INS noted that “by their nature, VAWA cases generally possess factors that warrant consideration for deferred action,” the agency instructed officers to ensure that requests receive adequate individual review. Since its formation, DHS has continued to provide individualized review to VAWA self-petitioners along these lines.

Following its experience in applying deferred action to VAWA self-petitioners, in 2000, INS initiated similar procedures for applicants seeking nonimmigrant status or visas created under the Victim of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (“VTVPA”). VTVPA introduced two new nonimmigrant visa classifications – a “T” visa available to victims of human trafficking and their family members, and a “U visa” for victims of other crimes and their family members. A year later, the INS released a memorandum directing immigration officers to assign possible victims to categories, and to use “existing authority and mechanisms such as parole, deferred action, and stays of removal” to avoid removal of those victims “until they have had the opportunity to avail themselves of the provisions of the VTVPA.” This step aimed at providing a mechanism that would offer the cooperating victims humanitarian protection and allow them to remain in the United States to assist with the investigation. Subsequent memoranda then instructed officers to assess deferred action for “all T visa applicants whose applications have been determined to be bona fide,” and all U visa applicants “determined to have submitted prima facie evidence of [their] eligibility.”

Upon its creation in 2003, DHS similarly made deferred action readily available to classes of undocumented immigrants with strong humanitarian claims against deportation. In 2005, the devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina temporarily prevented several thousand foreign students from fulfilling the requirements for maintaining their lawful F-1 nonimmigrant student status, because their schools were damaged, demolished, or otherwise unable to hold classes. At that time, DHS announced it would grant deferred action to those who were unable to maintain F-1 status directly due to consequences of the hurricane. To obtain deferred action, these affected students were required to submit an application that included a specific request for relief accompanied by an explanation of why they were unable to fulfil F-1 requirements. DHS reviewed these requests “on a case-by-case basis,” providing no assurance that all requests would be approved.

Additionally, in 2009, DHS further implemented a policy of offering deferred action to a specific class of aliens, initiating a program for certain widows and widowers of U.S. citizens and their qualifying children residing in the United States. Previously, USCIS did not provide relief to spouses or children of deceased U.S. citizens in any systematic manner, meaning that the surviving spouse could be deported if he or she was married to the U.S. citizen for less than two years at the time of the citizen’s death and the USCIS had not yet ruled on the spouse’s petitions. Again, USCIS applied an individualized assessment of the spouse’s request for relief under the policy, and a grant of deferred action was not guaranteed. Specifically, an application could be disapproved in the presence of “serious adverse factors, such as national security concerns, significant immigration fraud, commission of other crimes, or public safety reasons.”

As the OLC memo states, “although the practice of granting deferred action ‘developed without express statutory authorization,’ it has become a regular feature of the immigration removal system that has been acknowledged by both Congress and the Supreme Court.”