For an updated analysis of the Mexican asylum system, please see Mexico’s Asylum System: Good in Theory, Insufficient in Practice, posted 3/14/2023.

On July 16, 2019, the Trump administration implemented a new rule requiring migrants who travel by land to the U.S. southern border to apply for asylum and be denied in one of the countries they passed through before they can seek asylum in the U.S. (with limited exceptions). The rule effectively requires Central Americans arriving at the U.S. Southern border to seek asylum in Mexico prior to seeking it in the United States. The rule is currently in effect despite pending litigation.

Requiring migrants to seek asylum in Mexico may seem to be a reasonable alternative to seeking asylum in the U.S., but the Mexican asylum system is restrictive, severely underfunded and underdeveloped, and faces significant staffing and infrastructure limitations. These inadequacies create a dysfunctional system that is unable to meet the current humanitarian crisis and exposes vulnerable asylum seekers to mistreatment and dangerous conditions in Mexico.

What funding challenges does the Mexican asylum system face?

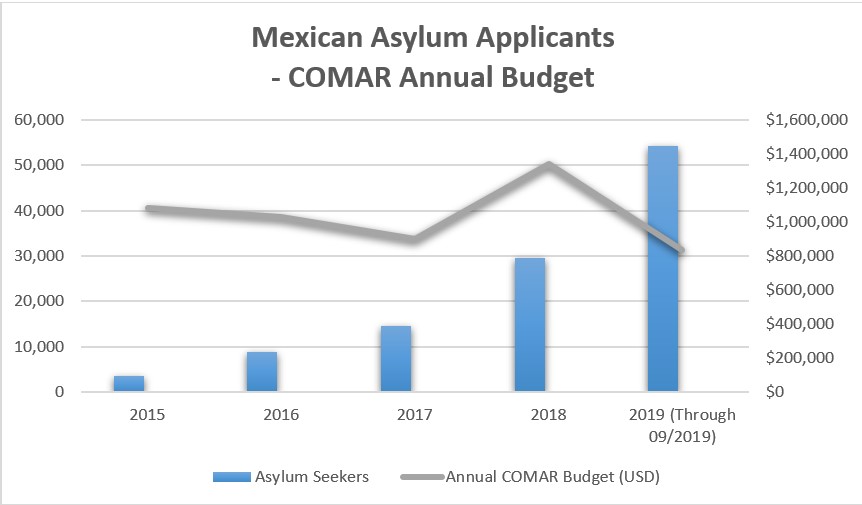

The Mexican asylum system is severely underfunded, with a minuscule budget and a mushrooming caseload. In 2014, Mexico received a total of 2,137 applications for asylum. In 2017, that number ballooned to 14,596, increasing again in 2018 to 29,693 asylum claims, representing nearly fourteen times as many applications as four years prior. The Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) struggles to operate with an extremely limited total budget of $1.1 million USD in 2017, an amount that has not kept pace with the increasing number of applications. This limited budget restricts COMAR’s ability to staff enough personnel to handle its rapidly growing caseload. While recent additional U.N. funding allowed COMAR to hire 29 new staff members, the Commission still lacks the resources to remedy the problem.

Figure 1 – Mexican Asylum Applicants and COMAR Annual Budget[1]

Sources: Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR) and Transparencia Presupestaria

Sources: Comisión Mexicana de Ayuda a Refugiados (COMAR) and Transparencia Presupestaria

Comparatively, the U.S. adjudicated nearly 82,000 affirmative asylum cases in 2018. The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the agency within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) responsible for immigration and asylum claims, had an enacted 2018 budget of $345 million for Asylum, Refugee, and International Operations. The budget for 2019 is $337.5 million. Another comparison can be made to the Canadian asylum system. Canada received 50,420 asylum claims in 2017, and its budget is about 24 times higher than Mexico’s budget.

Funding limitations also restrict the Mexican government’s ability to construct adequate infrastructure to handle the influx of asylum seekers to Mexico. COMAR’s three on-site facilities, one in Mexico City and two in Southern Mexico, are understaffed and overwhelmed. In 2017, Human Rights First reported that COMAR staff members were regularly working twelve hours a day, with rapidly increasing caseloads leading to high burnout rates and staff turnover.

As the number of asylum seekers arriving to Mexico continues to grow, the allocated budget has not met the growing need, with COMAR’s budget falling between 2015 and 2017 even as asylum applications skyrocketed.

How does the Mexican asylum system operate?

On paper, the Mexican asylum system is relatively generous, with a broad, internationally acceptable definition of “asylee.” In practice, the Mexican asylum system is extremely dysfunctional. Under Mexican law, an asylee is a person fleeing persecution in their home country and seeking and obtaining protection from inside Mexico. An asylee must meet either (1) the international definition of a “refugee” – a person with well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group, who has been forced to flee his or her country – or (2) the broader definition of “refugee” found in the Cartagena Declaration. Under the Cartagena Declaration, individuals whose lives have been threatened by generalized violence (including gender-based violence), but are not considered refugees under the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, may be recognized as refugees who are eligible for protection. Mexico is one of the fourteen Latin American countries that have incorporated the Cartagena Declaration’s broader definition of persons in need of international protection.

The Mexican asylum system is inadequate to handle the scope of the humanitarian crisis evident on the southern border of the United States

However, lack of funding, high rates of staff turnover, low salaries and inadequate training of personnel has led to inconsistent outcomes and mismanaged cases. According to a leading advocate, the asylum adjudication system in Mexico “depends more on who reviews the case” than the strength of an asylum seeker’s case, leading to outcomes inconsistent with due process.

Advocates have reported cases in which migrants appear to meet the standard for protection, but are denied asylum mistakenly or unfairly. In particular, COMAR adjudicators regularly deny asylum to individuals from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras under the false assumption that they can be safely repatriated to their home countries.

How can an individual apply for asylum in Mexico?

An individual applies for asylum by submitting an application to COMAR or Mexico’s National Institute of Migration (INM) within 30 days of entering Mexico. COMAR along with INM process refugee and asylum claims.

After submitting an application form with personal information including reasons for leaving the country of origin, COMAR schedules interviews at which an applicant explains the facts that motivated his or her departure from the country of origin and provides supporting evidence. When necessary, the Mexican government is required to provide the applicant with assistance from a translator or interpreter. Applicants can be transferred to detention centers and held in detention throughout the duration of the application process.

Process

- Once an application is submitted, the applicant receives proof of application demonstrating that he or she has begun the administrative process with COMAR. This document guarantees temporary lawful status in Mexico.

- If COMAR grants asylum status, the individual must apply for permanent residency at INM. Every family member included in an application will be recognized as an asylee.

- If the asylum application is denied, the individual has the right to appeal the decision. If an appeal is denied, the individual has the right to receive legal assistance to continue the appeal process in front of a judge, or has the option to return to his/her country of origin.

- The application process is free. In addition, Mexico offers humanitarian visas for no cost to a limited number of individuals that allow migrants to move about the country freely and work for up to a year.

Criticisms

- Advocates and lawyers have found that the Mexican asylum system fails to adequately screen and evaluate those in need of humanitarian relief. Generally, officials do not conduct initial screenings of migrants to establish whether they are in need of protection. Advocates have noted that when screening interviews do occur, they can be inadequate. For example, COMAR often conducts interviews without translation services for non-Spanish speaking indigenous populations. Often, migrants seeking protection are detained by Mexican enforcement officials and sent directly into the deportation process.

- Advocates have reported that Mexican authorities use intimidation and threats to dissuade asylum seekers, with the INM regularly warning migrants that they will face lengthy stays in detention if they seek asylum. This intimidation tactic forces many potential asylum seekers to sign documentation stating a preference for voluntary deportation. Advocates have argued that this practice amounts to refoulement, or the forcible return of an individual to a country where they would be at risk of harm, in violation of international law.

Does the government provide asylum seekers with appointed immigration lawyers?

In theory, yes. The law establishes that every applicant has the right to an attorney and free legal assistance through the Federal Institute for Public Defense, including during the appeals process.

In practice, asylum seekers in Mexico have great difficulty obtaining counsel. Due to the shortage of qualified attorneys and underfunded and understaffed non-profit legal providers, people navigating the Mexican asylum system struggle to obtain representation. The lack of legal representation puts asylum seekers at a major disadvantage, given Mexico’s short filing deadlines and complex case transfer procedures. Observers have condemned the government’s inability to meet regularly this requirement for free legal assistance.

How long does the asylum process take?

In theory, 55 business days. Under Mexican law, COMAR must evaluate the application and issue a decision within 55 business days (45 days to reach a decision, plus 10 days to inform the applicant of the decision). For appeals, COMAR has up to 90 days to review decisions.

However, in late 2017, COMAR announced that due to a lack of resources and growing backlogs, it was suspending the processing time requirement. Recent data shows that decisions are taking much longer, as long as two years in some cases.

Can an asylee become a Mexican citizen?

Yes. An individual who has been granted refugee status can apply for Mexican citizenship after he or she has resided in Mexico for two years, provided the individual has not left Mexico for a single period of more than six months.

Where do asylum applicants seeking resettlement in Mexico come from?

Primarily Honduras followed by El Salvador and Venezuela. According to COMAR, during the first half of 2019, the countries with the most asylum applications were Honduras (16,371), El Salvador (4,753), Venezuela (3,622), Cuba (2,713), Guatemala (1,590), and Nicaragua (1,064).

What dangers do asylum seekers face in Mexico?

Asylum seekers in Mexico face threats and danger from criminals. The U.S. Department of State maintains a travel advisory for Mexico, citing threats related to violent crime, kidnapping and robbery. In 2018, it was reported that 4,000 migrants have died or gone missing en route to the U.S. over a four year period. Mexico’s Commission on Human Rights reports the discovery of mass graves and evidence of executions, demonstrating the severity of violence faced by migrants. In some circumstances, migrants have “disappeared,” been kidnapped and sold to human traffickers who place them into forced labor and exploit them.

Conclusion

The Mexican asylum system is inadequate to handle the scope of the humanitarian crisis evident on the southern border of the United States. The current system of insufficient infrastructure, legal representation, and due process is an unfair environment to adjudicate asylum cases where repercussions could be a matter of life or death. Central Americans fleeing persecution, violence, and corruption are entitled to fair treatment, and the U.S. asylum system is better prepared to manage their asylum cases. The U.S. asylum system has experience handling large numbers of asylum claims and sufficient resources to ensure fair adjudication and asylee well-being during the adjudication process.

Thank you to Nathaniel Harrison for his assistance with this article.

[1] All monetary figures have been converted to USD from Mexican Pesos based on 10/09/19 exchange rates.

Author: Dan Kosten